996 THE PRINCE OF THE PYRENEAN PASTURES

THE PRINCE OF THE PYRENEAN PASTURES

by David Hancock

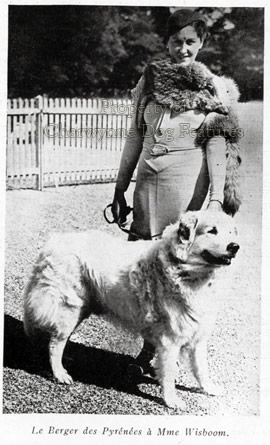

In 2011, the fanciers of the Pyrenean Mountain Dog issued a, brief but quite excellent, well-illustrated brochure on their breed, to be valued because of its remarkable honesty and as an admirable example to other breed fanciers whose breed has similarly lost its way. In this brochure, they argue that true type and the sheer essence of the Pyrenean is being lost in the British show ring. They emphasize that the show ring must not promote selection on the basis of fashion and exaggeration. They considered that fashion was winning over true type, mainly through judges who have never learned or who have just lost sight of the breed’s original purpose. They point out that over the years, the handsome, working, ‘rustique’ dog has been steadily replaced by a glamorous, over-coated and back-combed dog. They remind fellow fanciers that any dog able to work on high, exposed mountainsides must have a lean and muscular build and a weatherproof coat, and they end with a plea for them to respect the ‘dog of the mountains’. I salute them for this publication and applaud their criticism of judges who resort, in their after-show critiques, to words such as ‘cobby’ and ‘upstanding’ that simply do not reflect the Breed Standard for the breed.

In 2011, the fanciers of the Pyrenean Mountain Dog issued a, brief but quite excellent, well-illustrated brochure on their breed, to be valued because of its remarkable honesty and as an admirable example to other breed fanciers whose breed has similarly lost its way. In this brochure, they argue that true type and the sheer essence of the Pyrenean is being lost in the British show ring. They emphasize that the show ring must not promote selection on the basis of fashion and exaggeration. They considered that fashion was winning over true type, mainly through judges who have never learned or who have just lost sight of the breed’s original purpose. They point out that over the years, the handsome, working, ‘rustique’ dog has been steadily replaced by a glamorous, over-coated and back-combed dog. They remind fellow fanciers that any dog able to work on high, exposed mountainsides must have a lean and muscular build and a weatherproof coat, and they end with a plea for them to respect the ‘dog of the mountains’. I salute them for this publication and applaud their criticism of judges who resort, in their after-show critiques, to words such as ‘cobby’ and ‘upstanding’ that simply do not reflect the Breed Standard for the breed.

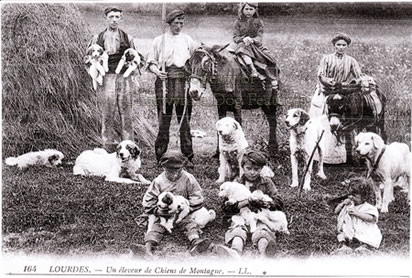

The ease of modern living has led to our devaluing the contribution made throughout human history by such flock protectors, but our ancestors prized them and developed them as highly impressive, extraordinarily robust, canine specimens. We must be careful with the surviving breeds not to substitute show-ring criteria for functional need. Huge cow-hocked, straight-stifled, over-coated, under-muscled shepherd's mastiffs would not have lasted long in the demanding pastures of past centuries. Our respect both for our rural heritage and those breeds surviving man's changing requirements needs to be demonstrated by a seeking of soundness before ‘stance’ and fitness ahead of flashiness. These quite remarkable faithful, selfless, admirable dogs, often killed by marauding packs of predatory wolves, deserve no less. With around 330 sheep currently being killed annually by bears, reintroduced from the Czech Republic into the Pyrenees, perhaps the reintroduction too of the shepherd’s mastiff, more determined than the mountain dogs, would be timely. The value of breeds like the Pyrenean Mountain Dog used to be hugely accepted but now, perhaps understandably, their use and value has altered in an increasingly urban world. Wherever sheep needed guarding - they were there!

From Portugal in the west, right across to the Lebanon and then on to the Caucasus mountains in the east, from southern Greece, north through Hungary to most parts of Russia there are powerful pastoral dogs like this to be found, developed over thousands of years to protect man's domesticated animals from the attacks of wild animals. Some are called shepherd dogs, others mountain dogs and a few dubbed 'mastiffs', despite the conformation of their skulls. Their coat colours vary from pure white to wolf-grey and from a rich red to black and tan. Some are no longer used as herd-protectors and their numbers in north-west Europe dramatically decreased when the use of draught dogs lapsed. A number of common characteristics link these widely-separated breeds: a thick weatherproof coat, a powerful build, an independence of mind, a certain majesty and a strong instinct to protect. As a group, they would be most accurately described as the flock guardians. In North America they are usually referred to as Livestock Protection Dogs or LPDs.

In south-west Europe these dogs became known in time as breeds such as the Estrela Mountain Dog and the Rafeiro do Alentejo of Portugal and the Spanish or Extremadura 'Mastiff'. To the north-east of the Iberian peninsula, such dogs became known as the Pyrenean Mountain Dog or Patou, on the French side, and, separately, on the Spanish side, as the Pyrenean 'Mastiff'. In the Swiss Alps they divided, as different regions favoured different coat colours and textures into the 'sennenhund' or mountain pasture breeds we know today as the Bernese, Appenzell, Entlebuch and Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs and the Alpine Mastiff, which is behind the St Bernard, a breed once much more like the flock-guardian phenotype. In Italy, local shepherds favoured the pale colours now found in the Maremma Sheepdog and the very heavy coat of the Bergamasco. In the north-west of Italy, the Patua or Cane Garouf, the Italian Alpine Mastiff may soon be lost to us. In Corsica, their flock protector, the Cursinu, is also under threat as numbers fall. In the Balkans, similarly differing preferences led to the emergence of the all-white Greek sheepdog and the wolf-grey flock guardians of the former Yugoslavia, the Karst of Slovenia, the Tornjak or Croatian Guard Dog and the Sar Planninec of Macedonia.

It is forgiveable to believe that such breeds are sizeable because they need to be able to see off wild animals that prey on sheep. But much more important are the bigger stride afforded by size, the ability to carry more fat reserves and store more heat than a small dog and to survive disease, severe weather and the odd accident - big bones break less easily than tiny ones. This is why such breeds possess a similar phenotype; the Estrela Mountain Dog is easily confused with a Slovenian Karst or Caucasian Owtcharka, or a Maremma with a Tatra Mountain Dog. The Caucasian Owtcharka can resemble the early St Bernards, the Alpine flock guardian, too. The shepherds, drovers, stockmen and traders in such dogs knew what made a dog effective and therefore more valuable. It is wrong however to breed for great size alone in such breeds, dogs on long migrations were 60lbs weight not the 100lbs+ often desired in breeds like the St Bernard and the Newfoundland, that suffer badly in extreme heat. The warmer the migration route the lighter the dogs had to be to cope with the temperature. The more substantial dogs – with heftier frames, able to conserve heat – featured further north or purely in mountainous regions.

I do wish the kennel clubs of the world would get their act together over the nomenclature used for pastoral breed titles. The flock guarding breeds, like the Anatolian Shepherd Dog, should not be called ‘shepherd dogs’; the herding breeds like the Belgian and Dutch Shepherd Dog breeds are best described by this title. But when is a sheepdog not a shepherd dog? Is there a difference in role here? The Pyrenean pastoral breeds make a point for me: the biggest, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog is the flock guardian, with the size and role of the Hungarian Kuvasz; the next down in size, and on the Spanish side of the range, but more fiercely protective is the Pyrenean Mastiff, a shepherd’s mastiff, with the size and role of the Tibetan Mastiff; then comes the Labrit or Pyrenean Sheepdog, a much smaller, much more active herding breed, but appreciably smaller and with a different role from our working collies. Breed titles should reflect breed purpose. Their role gave them their phenotype, their temperament and their nature. These are breed points as, if not more, important than show ring breed points, such as skull shape and ear and tail carriage. Breed type originated in function not appearance.

I do wish the kennel clubs of the world would get their act together over the nomenclature used for pastoral breed titles. The flock guarding breeds, like the Anatolian Shepherd Dog, should not be called ‘shepherd dogs’; the herding breeds like the Belgian and Dutch Shepherd Dog breeds are best described by this title. But when is a sheepdog not a shepherd dog? Is there a difference in role here? The Pyrenean pastoral breeds make a point for me: the biggest, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog is the flock guardian, with the size and role of the Hungarian Kuvasz; the next down in size, and on the Spanish side of the range, but more fiercely protective is the Pyrenean Mastiff, a shepherd’s mastiff, with the size and role of the Tibetan Mastiff; then comes the Labrit or Pyrenean Sheepdog, a much smaller, much more active herding breed, but appreciably smaller and with a different role from our working collies. Breed titles should reflect breed purpose. Their role gave them their phenotype, their temperament and their nature. These are breed points as, if not more, important than show ring breed points, such as skull shape and ear and tail carriage. Breed type originated in function not appearance.

108 Pyrenean Mountain Dogs were newly registered in Britain in 2015, compared, say, to 27 Maremma Sheepdogs and 9 Estrela Mountain Dogs and only 3 Anatolian Shepherd Dogs; this type of dog isn't thriving in the show ring and its fanciers are going to have to work hard to conserve such admirable dogs with such a magnificent record of service to man - usually in remote and challenging regions. Such dogs have had much of their protective nature 'bred out' but still care for their owners, and especially their children, in a quite magnanimous manner. They bring a natural dignity, considerable canine handsomeness, a stable predictable temperament and a certain grandeur into our lives. As an estate guard-dog, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog would bring deterrence without overt aggression, a sense of demonstrating their 'ownership' of their family's territory - if not the family itself! But whatever their designated role, they do not need giant size, heavy overcoats, poor construction, especially in the hindquarters, or to become a suburban trophy for humans to show off. They deserve to be bred as true mountain dogs: sizeable but not too vast for their own well-being, physically sound without exaggeration and friendly without losing their natural suspicion of strangers. If they are truly bred like a mountain dog in type and temperament, then their future will become much more assured. This really is a breed worth owning - and certainly saving!