990 THE DOGS OF SCANDINAVIA

THE DOGS OF SCANDINAVIA

by David Hancock

The dog breeds of Scandinavia very much reflect the terrain of each country there, as well as how far north and mountainous that terrain is. The spitz breeds, with their heavier coats and more protected ears are more numerous further north and the smooth-haired, drop-eared hounds further south. Here, I use the word Scandinavia to embrace Norway and Sweden, Finland and Karelia (now in Russia), the Faeroe Islands and Iceland. The dogs there are remarkably similar, reflecting shared history. The Scandinavians still have their herding dogs, of the classic spitz type of the arctic north, and surprisingly similar in each country. When on an exploration trip to one of Iceland’s ice-caps, Hofsjokull, in the middle of the last century, I was intrigued to see what looked like a prick-eared, bushy-tailed collie on several farms there. Known locally as the Islandske Spidshunde and used to round up ponies as well as sheep, they have earned mentions both by Dr Caius and Shakespeare. The Icelandic Sheepdog is long-established and very collie-like, as is the Buhund or cattle dog of Norway, now becoming known in our show rings. They are encouragingly inspoiled.

The dog breeds of Scandinavia very much reflect the terrain of each country there, as well as how far north and mountainous that terrain is. The spitz breeds, with their heavier coats and more protected ears are more numerous further north and the smooth-haired, drop-eared hounds further south. Here, I use the word Scandinavia to embrace Norway and Sweden, Finland and Karelia (now in Russia), the Faeroe Islands and Iceland. The dogs there are remarkably similar, reflecting shared history. The Scandinavians still have their herding dogs, of the classic spitz type of the arctic north, and surprisingly similar in each country. When on an exploration trip to one of Iceland’s ice-caps, Hofsjokull, in the middle of the last century, I was intrigued to see what looked like a prick-eared, bushy-tailed collie on several farms there. Known locally as the Islandske Spidshunde and used to round up ponies as well as sheep, they have earned mentions both by Dr Caius and Shakespeare. The Icelandic Sheepdog is long-established and very collie-like, as is the Buhund or cattle dog of Norway, now becoming known in our show rings. They are encouragingly inspoiled.

The northern Scandinavian herding dogs range from the corgi-like to the collie-like, with the Norwegian Senjahund and the Swedish Vastgotaspets or Vallhund exemplifying the former and the maastehund of the Lofoten Islands, the Finnish, Swedish and Lapponian Herders resembling the latter. The corgi-type heelers like the Vallhund, have to be agile, quick and alert, if only to survive. As cattle dogs, as discussed in an earlier serials, they have to learn to bite the hind foot that is bearing weight, giving them that extra split second to duck or flatten to avoid the reacting hefty kick. They learn too to attack alternate feet, rather than repeating the first attempt, just to gain a little more surprise. The Finnish Lapphund seems to be making progress here, although it was only recognized by the Finnish KC in the 1950s and separated from the smooth variety in 1967. This breed was introduced into Britain by Roger and Sue Dunger (Sulyka) and their enthusiasm has done much to promote this attractive breed here. Hardy, double-coated, working dogs, they have been bred by the Sami people of Lappland in Northern Scandinavia for centuries to herd their reindeer.

Any hound capable of working successfully in sub-Arctic conditions, treacherousmountain terrain and in huge expanses of largely uninhabited regions surely demands our admiration. Why then have the ‘spitz-hounds’ not attracted our interest? Books on hounds usually overlook the northern breeds, which can range from the Elkhounds of Scandinavia to the bear-dogs of Karelia. Somehow the appearance of such hounds, with their prick ears, thick coats and lavishly-curled tails, doesn’t immediately fit our mental image of a scenthound. The Finnish Spitz is already well known here, with 36 newly registered with the Kennel Club in 2010, but only 14 in 2015. They have been grouped with the Hounds by the KC, but as a ‘bark-pointer’ should perhaps be allotted to the Gundog Group. This attractive little breed is a most unusual, for us, that is, hunting dog, in a style not utilised in Western Europe. The dog is used in heavily wooded areas where it uses sight, scent and unusually good hearing to locate feathered game, upland game such as grouse or capercaillie. The location of the quarry is ‘pointed’ by a special stance, four-square with tail up twitching with excitement, head back and giving voice – a distinctive singsong crooning bark, which is sustained, both to mesmerize the prey and attract the hunter.

This ‘point by bark’ has to be audible to the hunter, who may be some distance away, and more importantly to ‘freeze’ the bird. The Finns claim that the tone of the bark, the agitated almost hypnotic waving of the bushy tail – and even the small white spot on the dog’s chest, hold some kind of fascination for the bird, which watches intently from the relative if temporary safety of its perch. There are similarities here with the flamboyantly-waving tail of the old red decoy dog of East Anglia, used to lure ducks for the hunter. The Finnish Spitz has the same rich rufous, almost red-gold coat, mobile ears and highly inquisitive nature. Just as this breed is the national dog of Finland, so too is the Elkhound that of Norway and the Hamiltonstovare (the word stovare coming from the Low German stobern – seeking or tracking) that of Sweden, a breed used as a single tracker, i.e. used alone to follow a track not as a pack hound.

Thirty years ago, we began to show an interest in a handsome Swedish scenthound breed, the Hamiltonstovare, very similar, at first glance, to the Finnish Hound. Eight were registered in 1984, 21 in 1990, 31 in 1991, only 6 in 2010, then 27 in 2011 but only 6 again in 2015. These figures are not reassuring; this is an attractive breed, but, as always, hound breeds are not ideal pets for those with no sporting facilities. Here, from the ringside, I’ve been impressed by an import Santorpets Tessie at Sufayre, every inch a hunting dog. This breed was created by a devoted sportsman, bred specifically for a sporting function and one needing exercise, stimulation and above all, scent. This breed is used as a single working hound for finding, tracking and driving hare to the guns, with the hunters using horns to communicate, but relying on the baying of the hounds for information too. They just don’t look at home in a suburban street. The Gotlandstovare, another scenthound of similar appearance is hardly known outside its native country.

Thirty years ago, we began to show an interest in a handsome Swedish scenthound breed, the Hamiltonstovare, very similar, at first glance, to the Finnish Hound. Eight were registered in 1984, 21 in 1990, 31 in 1991, only 6 in 2010, then 27 in 2011 but only 6 again in 2015. These figures are not reassuring; this is an attractive breed, but, as always, hound breeds are not ideal pets for those with no sporting facilities. Here, from the ringside, I’ve been impressed by an import Santorpets Tessie at Sufayre, every inch a hunting dog. This breed was created by a devoted sportsman, bred specifically for a sporting function and one needing exercise, stimulation and above all, scent. This breed is used as a single working hound for finding, tracking and driving hare to the guns, with the hunters using horns to communicate, but relying on the baying of the hounds for information too. They just don’t look at home in a suburban street. The Gotlandstovare, another scenthound of similar appearance is hardly known outside its native country.

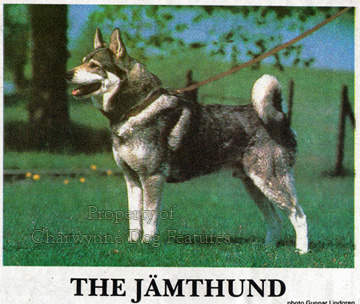

There are over eight breeds of native hunting dog in Sweden, ranging from the better known Grey Elk Dog or Jamthund, a handsome cream-marked grey, (only recognised in 1946 but widely used in hunting trials), the Swedish White Elkhound (nearly 800 registered each year), the little known Ottsjojim, an elkhound of Jamthund type, to the well established Drever, or Swedish Dachsbracke (between 12 and 16 inches high), the bigger black and tan Schiller and Smalands Hounds and the Hamiltonstovare. Not surprisingly, the non-spitz hounds greatly resemble their Norwegian equivalents: the Halden (only 6 registered in 1980, against over 600 Schillers and 290 Smalands), Hygen and Dunker (now the Norwegian) Hounds. The German influence can be seen in a number of these, with the bob-tailed Smalands looking very Rottweiler-like, even though scenthounds in Germany are not numerous, as hunting dogs, or popular as pets. As hunting dogs they are famed trackers, not hounds of the pack. Sweden also boasts a small hunting dog, the Norbottenspets, used in hunting rabbits and hares. It is not always easy to identify these breeds, the climate and the conditions has shaped them and their similarity of form is understandable.

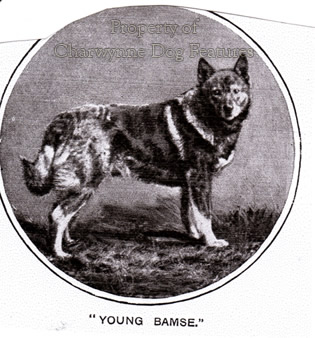

The best-known Spitz-hound in Britain is the Norwegian Elkhound, although its fortunes have varied. Ten years ago, 149 were newly registered with our KC; in 2010, just 33, 51 in 2015. Comments on the entry at championship shows in 2011 by judges of this breed give concern. These range from “Upright shoulders and wide chests accounted for bad front movement and incorrect rear angulation prevented the correct drive from behind” and “…loose elbows and pasterns were evident in most exhibits” to “Hind movement overall was not good, particularly in the males…they were straight in angulation in front and rear and therefore lacked both reach and drive.” The Norwegian hunters I met disapproved of too straight a stifle, arguing that such a feature made the hound ‘use its back too much’ and lacked endurance as a result. A 2012 show critique expressed concern about ‘an ever diminishing gene pool’ and the necessity to introduce new bloodlines ‘to preserve the breed as we know it’. We all know that this is a breed that relies on endurance and these judges’s criticisms are worrying for the future of the breed here, famous as a working hound. I believe one has been used as a locator of people buried under snow by the Scottish Mountain Rescue Services. The Elkhounds I have seen in Norway looked stockier and shorter-coupled than those I saw in the United States, where I was saddened to see them lighter and finer-boned – and expected to ‘gait’ at speed in the ring, rather like Siberian Huskies. I don’t think Norwegian elk-hunters would want their precious dogs to perform in such a way!

Hounds like the Norwegian Elkhound have been used for centuries to hunt bear, elk, reindeer and the wolf, but it was not until 1877 that they were recognised as a breed there. Only those that qualify in hunting trials may be awarded the full title of champion. This surely has to be the way ahead for all sporting dogs if they are to be retained as such. The Elkhound hunts mainly by scent, working silently to locate its prey, which it then holds or drives towards the hunters. As it doesn’t actually ‘catch and kill’ its quarry, strictly speaking it shouldn’t be classified as a hound. (But under our own Hunting Act, aren’t all hounds now gundogs?) Usually a shade of grey, with black tips, a black cousin is found in the Finnmark area, with a shorter coat, looking taller and lighter than the Norwegian breed. I saw some sixty years ago when exploring the Jaeggevarre ice-glacier region; the local hunters called them Sorte Dyrehund - they were leggy and thick-coated, hinting at great robustness and stamina. There is also the Halleforshund, an elkhound breed that is red-coated with a black mask, more like one of the laika breeds further east.

At World Dog Shows, especially the one held in Helsinki, I have been impressed by the Laika type, especially the imposing Karelian Bear Dog, a sturdy mainly black breed, used for hunting the bear, lynx and elk, but prized especially on sable. Determined, fiercely-independent and immensely resolute, which is hardly surprising when you think of their bigger quarry, they have a very acute sense of smell and superb long-sight, picking up movement at extreme distances. This breed originated in Karelia, a territory stretching from north of St Petersburg to Finland, with the Russian breeders adding Utchak Sheepdog blood for greater resistance to the cold. Twenty two inches high and around 55lbs in weight, they were originally used to hunt elk, then later to hunt bears and large game. They are related to the Russo-European Laika, often being black-coated and with a similar broad head, but easily confused with the hunting dogs from further east: the Western and Eastern Siberian Laikas. These hunting dogs have quite remarkable resistance to low temperatures and their past value to peasant hunters, especially before the arrival of firearms, must have been immense. I am told that around 70,000 hunting Laikas are in East Siberia alone, with those used on feathered game selected for air-scenting, those used on fur or hoof bred for ground-scenting skill.

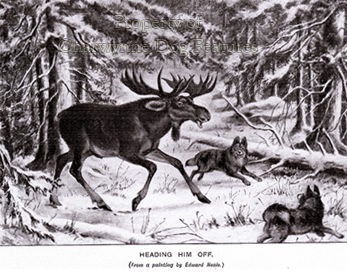

Both the bear and the elk are formidable adversaries, with even the baying dogs being regularly killed by them. An elk, or moose in North America, is the largest living deer, about the size of a horse; the bull can have antlers of up to 40 points. The use of dogs for elk-hunting in northern Europe has a long history. It took two forms: one with wide-ranging free-hunting small packs (loshund) and another with dogs on a long leash (lurhund or bandhund) following a trail. The latter demanded close cooperation between dog and handler, to make full use of the wind conditions and not to startle the quarry into hasty retreat. The hound must not give tongue or the elk accelerates and can be lost. Hunting bears too was not a practice for the fainthearted in times when only primitive weapons were available. Canada had an equivalent to the Karelian Bear Dog, the Tahltan Bear Dog, used by the Tahltan Indians of British Columbia, south of the Yukon and flanked by Alaska. It was used in packs to hunt black and grizzly bears and the lynx. Even more specialist was the Norwegian Lundehund, used to hunt puffins on coastal cliffs. Uniquely, this breed has the ability to fold its ears shut, using a cartilage around the ear-rim, and, six toes on each foot, rather than four. Hunting for puffins’ nests clearly demands extra features in the hound!

But of all these Scandinavian breeds, and they range across a wide field, there is one breed that has constantly impressed me, both in stature and in reputation as a field dog, and that is the Finnish Hound. Not surprisingly, many were exhibited at the Helsinki-staged World Dog Show and I was very taken by the sheer uniformity throughout the entry and the admirable soundness of nearly every exhibit; their breeders have clearly done a quite outstanding job with this handsome breed. This example of diligent breed-custodianship is so encouraging but sadly not always the case. I congratulate the Finns concerned at every level on such an achievement; the dogs of Scandinavia are well worth conserving. The Scandinavian breed that interests me the most, is a Danish breed and one almost lost to us: the Broholmer, a breed truly meriting the title of 'Great Dog of Denmark' .

I can find no reason for the breed of Great Dane to be so named. The French naturalist Buffon (1707-1788), responsible for so many canine misnomers, called it 'le grand Danois' but, knowing his fallibility, he could have been mishearing the words 'Daim' (buck) or 'Daine' (doe), French for fallow deer, 'daino' in Italian, when packhounds used to hunt deer were referred to by sportsmen. Other references to a Danish dog could have been directed at the Danischer Dogge or Broholmer, the mastiff of Broholm Castle, a Great Dane-like if smaller breed (see below), now being resurrected by worthy Danish enthusiasts. In his authoritative 'Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports', published in 1870, Delabere Blaine records: "The boarhound in its original state is rarely met with, except in some of the northern parts of Europe, particularly in Germany...these boarhounds were propagated with much regard to the purity of their descent..." The breed known in England as the Great Dane is known on the continent as the Deutsche Dogge or German Mastiff and that I support. In the late 19th century, this breed was known as the Dogue Allemand and then only later as the Dogue Danois. For me, the Dogue Danois is the Broholmer.

The Broholmer is not likely to appear in Britain for some time, for its fanciers in its native land are determined to retain stock until such time as their own gene pool is satisfactory. The Broholmer Society now has over 300 members, with some 200 dogs registered. The rule over selling abroad will only be reconsidered when there are 300 dogs registered from 8 different lines. The selection programme began in 1974 and within 15 years 100 dogs suitable for registration had emerged. It was in 1974 that enthusiast Jytte Weiss wrote an article 'In Search of the Broholmer', after the last specimen of the breed was believed to have died in 1956. A responding telephone call to her brought to light an eleven year old dog, 78cms at the withers and weighing almost 80 kgs. This dog, when examined, met the demands of the 1886 breed standard. Other dogs of this type were then discovered.

At one time, it was believed that fawn was the classic colour for the breed, but researches revealed that there had been a black variety in the Grib Skov region of North Sjelland. The Danish kings apparently favoured the fawns in the hunting field, but farmers, butchers and foresters in that region preferred the black variety, the colour favoured too in the night-dogs at the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. This colour was accepted by the FCI in 1982, when the standard was accepted by them.

As the breeding programme developed blacks were mated with fawns but this produced tricolours, rather like the Swiss Cattle Dog breeds. Black to black matings were eventually dropped because the progeny lacked essential breed type. Fawns, from fawn parents, were bigger and stronger. The extant standard permits just three colours: clear fawn with a black mask/muzzle, deep fawn and black, usually with small white markings on the chest and toes. The ideal size is considered to be between 75 and 80cms at the withers. Great size is thankfully not desired and, commendably, balance, virility and health are considered a higher priority.

Leading fancier Jytte Weiss has stated that "we have paid particular attention to the very good character and mentality of the Broholmer." Although the guarding qualities of the breed are valued, a stable good-natured temperament, the famed magnanimity of the mastiff breeds and, especially, tolerance of children are wisely valued more. The more powerful the dog, the more caution has to be exercised in today's society. A disciplined biddable dog is also required by hunters. A bad-tempered hound is a menace in kennels; spirit and tenacity must never be confused with undesired aggression.

An under-rated figure in the survival of this once famous breed is Danish archaeologist Count Niels Frederik Sehested from Broholm. In the middle of the 19th century he had his interest aroused from old prints depicting the breed. His work led, in time, to 120 pups being placed with notable Danes who promised to promote the resurrected breed. Two of these were King Frederik VII and the Countess Danner, who referred to his pups as 'Jaegerspris' dogs, after the name of his favourite estate. One of these, Tyrk, can be seen, preserved, in the Museum of Zoology in Copenhagen. Large fawn dogs were subsequently bred on the estates of the Count of Broholm. Dogs of this appearance were also utilised by cattle dealers and, rather like the Rottweiler in Southern Germany, became known as 'slagterhund' or butchers' dogs. .jpg)

As most were in the Broholm area, the breed was renamed. The first breed standard was cast when the first Danish dog show was held in the gardens of Rosenberg Castle in 1886. In his monumental work 'Dogs of all Nations' of 1904, Van Bylandt described the breed as The Danish Dog or Broholmer, 29" at the shoulder, weighing about 125lbs and fawn or 'dirty yellow' in colour. He illustrated the breed with two dogs, Logstor and Skjerme, owned by J Christiansen and A Schested (sic) of Nykjobing. These dogs displayed bigger ears than the contemporary breed. The extant breed standard sets out, as faults, long ears and a long-haired coat, faults which English Mastiff breeders must now face. No mastiff breed will retain type unless faults are acknowledged and then remedied. English Mastiffs have relatively big ears, despite the standard's words on ears, as well as a lengthening of the coat, which is not being penalised. If essential breed type is to be conserved, all breeds must be bred to their own Breed Standard. It is so pleasing to know that the Broholmer is in safe hands. All the Scandinavian breeds of dog thoroughly deserve being conserved and treasured as part of their country's canine heritage.