986 CONSERVING OUR CATTLE-CURS

CONSERVING OUR CATTLE-CURS

by David Hancock

In his Collies and Sheepdogs of 1947, WL Puxley wrote: “ In bygone days the Welsh shepherds were accustomed to use a dog called a ‘heeler’, whose duty it was to drive the sheep away from the lowland pastures and force them back into the hills, the lower feed being reserved for the winter, when the hills were out of reach because of snow. These were mostly curs who bit the sheep and drove them off by force, but now the Welsh usually use their old dogs – the Bob-tails – who drive the sheep in any direction the shepherd wishes, and who can attain to a very high degree of perfection through their training.” We tend to use the word 'cur' in a derogatory manner these days, but the word was used to describe a nondescript working dog rather than a definite type. In The Sportsman's Cabinet of 1803, such a dog was described as "In colour the Cur is of a black brindled or of a dingy grizzled brown, having generally a white neck and some white about the belly, face, and legs; sharp nose; ears half pricked, and the points pendulous; coat mostly long, rough, and matted, particularly about the haunches, giving him a ragged appearance, to which his posterior nakedness greatly contributes, the most of the breed being whelped with a stumpy tail."

In his Collies and Sheepdogs of 1947, WL Puxley wrote: “ In bygone days the Welsh shepherds were accustomed to use a dog called a ‘heeler’, whose duty it was to drive the sheep away from the lowland pastures and force them back into the hills, the lower feed being reserved for the winter, when the hills were out of reach because of snow. These were mostly curs who bit the sheep and drove them off by force, but now the Welsh usually use their old dogs – the Bob-tails – who drive the sheep in any direction the shepherd wishes, and who can attain to a very high degree of perfection through their training.” We tend to use the word 'cur' in a derogatory manner these days, but the word was used to describe a nondescript working dog rather than a definite type. In The Sportsman's Cabinet of 1803, such a dog was described as "In colour the Cur is of a black brindled or of a dingy grizzled brown, having generally a white neck and some white about the belly, face, and legs; sharp nose; ears half pricked, and the points pendulous; coat mostly long, rough, and matted, particularly about the haunches, giving him a ragged appearance, to which his posterior nakedness greatly contributes, the most of the breed being whelped with a stumpy tail."

That sums up rather well many of the fox-like dogs I saw in my youth driving cattle on farms that I worked on. They were extremely valuable; researchers should never dismiss the word 'cur' as just derogatory. Watching a farmer drive cattle up a ramp at the Bath and West Show, many years ago, using a small terrier-like dog, I asked him what kind of dog he had; he replied that ‘she’s a nip ‘n’ duck dog’. It’s an instinctive inherited skill related to the dog’s size and agility. My Border Collies could drive cattle, heeler-fashion, but found moving horses too perilous. The Germans have lost their heeler: the red-brown cattle dog known as the Siegerlander Altdeutsche Hirtenhund or Kuhhund (cowdog); I never came across them on remote farms there. But I have seen spitz-type ‘cowdogs’ rounding up ponies in Iceland and cattle in Norway using this technique.

I first became aware of the heeler's skill in an unusual way: playing football with a fellow twelve year old who had a Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgi. The dog 'played' football with us, and every time it was threatened by a swinging foot, it flattened instinctively and the foot cleared its head. This was done with remarkable timing. I was impressed; later on, when this dog was mated to a local terrier, I obtained a pup, such was my admiration. This 'drop-flat' technique is a vital survival technique when back-kicking hooves respond to a small dog's quick nip. Clever experienced heelers will nip the rear foot that the cow is standing on, rather than the one free to kick. The approach is nearly always from behind: a quick nip and away This heeling skill was valuable when cattle needed to be moved: in markets or when loading lorries or railway trucks. Short-legged, terrier-like heelers were not an unusual sight in Britain in the last two centuries. If they had been gundogs or hounds whole libraries would be filled with tales of their deeds.

There has been speculation that the Welsh Corgis were taken to Wales by Viking invaders, with the Vallhund of Sweden identified as the source. I am not aware of the 'nip and duck' instincts of Scandinavian breeds, like the Vallhund, the Buhund or the Lapphund, but the Vallhund, whilst having its own distinct breed-type, is remarkably similar to the Pembroke Welsh Corgi. The Senjahund of Finmark is noticeably similar to our surviving English heeler, the Lancashire breed. Pastoral breeds accompanied migrants perhaps more than other types, rivalled only by hounds in value. It is easy to spot British influences in pastoral dogs used in former colonies. I have seen working sheepdogs here that could easily be taken for Australian Cattle Dogs or Australian Shepherds. These Australian dogs are covered later. When sheep were traded, the sheepdogs were often traded with them. In 1982 the Smithsonian Magazine in the United States produced a theoretical model of neoteny in dogs that indicated the development of the dog in various stages throughout domestication. This study showed heelers, huskies and corgis in the first move away from the wild dog, followed by the header-stalkers, the hunters and herders, then the other types, with the flock protection dogs, with their blunter heads and drop ears, a much later development. Head shape and ear carriage can have an influence on capability.

In 2015, there were only 366 Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgis newly registered with the Kennel Club, and just 124 of the Cardiganshire variety; now on the vulnerable breeds list. (The Lancashire Heeler is under even greater threat - only 81 being registered in 2015). Originally classified as one breed of Welsh Corgi, with only 10 being first registered in 1925, on their recognition, in 1950, there were well over 4,000 Pembrokes registered but only just under 170 of the Cardigan variety. Statistically it could be argued that the latter is maintaining its position better than the former, but it is the Cardigan that is rightly listed as vulnerable. Patronage from the royal family led to the astonishing rise in popularity of the Pembroke dog and it has retained a steadfast bunch of fanciers. This Welsh heeler has kept its perky nature and natural assertiveness, but has lost some of the ruggedness of the earlier types. It takes courage and technique to drive cattle, a dog lacking agility being at a distinct disadvantage. Nipping a one-ton bull then avoiding its resultant kick demands special qualities.

The origins of such heeler-cattle dogs are often the subject of fierce debate and remarkable ignorance from the strangely-revered dog writers, some of these can only think of a breed they don't know as having to come from one or two that they do know! EC Ash, in his Practical Dog Book of 1930, wrote, with astonishing certainty: "...they are a cross of Shetland Sheepdog with the Sealyham Terrier, and possibly Border Terrier..." But nine years later, was writing, absurdly in my view: "I am of the opinion...that the Welsh Corgi (Pembroke) is an Alsatian cross." About that time, Theo Marples was writing, equally absurdly: "Probably the Welsh Sheepdog and the Bull Terrier had a hand in his making." Clifford Hubbard however, who made a comprehensive study of the Welsh breeds, linked the Pembroke variety with Flemish weavers who settled in the Haverfordwest area in the eleventh century. He considered that these migrants brought their Schipperke-like dogs with them to provide an essential ingredient in the emerging breed. Hubbard knew a great deal about both Welsh dogs and pastoral dogs across the globe.

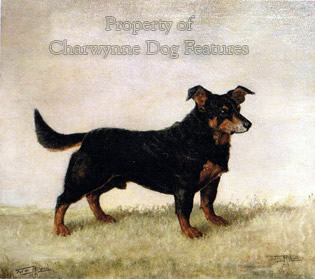

But what about the only surviving English heeler breed, the Lancashire Heeler? With under 100 being registered annually this breed has not yet achieved a sound future. This is very worrying news, firstly because we have lost too many of our native pastoral breeds, and, secondly because this is a breed well worth saving. A foot high, smooth-coated, black and tan or liver and tan, lively and perky by nature, they represent an ideal companion dog for many households. I do hope the show ring fanciers keep faith with the historic design of this breed and not produce, in time, Dachshund-like specimens with snipey jaws, bent legs and too low-to-ground a build. This is essentially a natural unexaggerated working breed, deserving to be conserved as just that. They are part of our pastoral heritage.

Worryingly, in 2005, a Lancashire Heeler judge concluded, in his show critique: “What on earth has happened to this lovely breed?…I find it hard to believe that the breeders have lost the plot so completely. I was startled at the lack of quality which was here today. Dogs of all shapes and sizes, too light boned, too big, badly constructed, indifferent heads, eyes and expressions, appalling fronts…Fronts are the worst I have seen in the breed…I think the breeders need a wake up call…” In 2009 the Crufts judge of Pembroke Corgis wrote: “Last year after Crufts, Albert Wight (the 2008 Crufts judge) had some harsh words to say about the breed and I must admit I can see his point. I know it’s easy to romanticize the past but remembering the 70s and early 80s, the ‘Yorkshire’ era with all those wonderful tricolours…it’s hard to deny that we’re not going through a vintage period in the 2000s”. If you consult such reports on the British heeler breeds, it is clear that there is a discernible lack of wisdom within the breeds and this is alarming. With registrations falling and judges voicing considerable disquiet, there is much to be done by their respective Breed Clubs to safeguard the future of these fine breeds; a clear statement setting out what a working dog needs to function, back to basics if you like, is desperately required.