948 FLOCK GUARDIANS OF THE STEPPES

FLOCK GUARDIANS OF THE STEPPES

by David Hancock

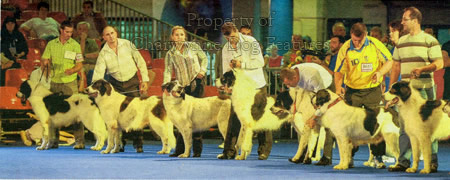

The imposing dogs of the flock guarding or mountain dog breeds from around the world have long found favour in Britain. Impressive breeds from Portugal in the west to Hungary in the east and from Turkey in the south to Germany in the north have found their way here. But the huge and often quite fierce pastoral dogs of Russia have yet to attract favour. Russian breeds like the Borzoi and the Samoyed have long been admired here and are now very much part of our dog show world. But the flock guardians or Owtcharkas from Central Asia, the Caucasus and Southern Russia, now the Ukraine, despite appearing at world dog shows, do not feature here. These three distinct breeds are strapping, assertive and very protective dogs of some stature but not exactly pets in our sense of the word. There were plenty at the World Dog Show held in Helsinki in 1998; some were very resentful of other dogs, many being muzzled, even in the ring. Several were 32 inches at the withers.

The imposing dogs of the flock guarding or mountain dog breeds from around the world have long found favour in Britain. Impressive breeds from Portugal in the west to Hungary in the east and from Turkey in the south to Germany in the north have found their way here. But the huge and often quite fierce pastoral dogs of Russia have yet to attract favour. Russian breeds like the Borzoi and the Samoyed have long been admired here and are now very much part of our dog show world. But the flock guardians or Owtcharkas from Central Asia, the Caucasus and Southern Russia, now the Ukraine, despite appearing at world dog shows, do not feature here. These three distinct breeds are strapping, assertive and very protective dogs of some stature but not exactly pets in our sense of the word. There were plenty at the World Dog Show held in Helsinki in 1998; some were very resentful of other dogs, many being muzzled, even in the ring. Several were 32 inches at the withers.

These distinct breeds are powerful, assertive and very protective dogs of some stature but not exactly pets in our sense of the word. The Caucasian sheepdog is very much like the Karst or Istrian sheepdog, the Sar Planinac or Macedonian/Illyrian sheepdog and similar to the brindle form of the Spanish Mastiff. There are, not surprisingly given the distances involved, different varieties of the Caucasian dog: the massive thickset type from Checheno-Ingush, NE of the Caucasus, the taller lighter type from Azerbaijan in the south-east towards Azarbayjan-e-Sharqi in Iran, the smaller squarer type of Dagestan, east of the Caucasus, and the big rangier Kangalian from the border area between Georgia and Turkey. Some experts claim that the best and most uniform specimens actually come from Georgia. Their restriction to these remote areas has led to these dogs being largely unknown in the West. They are becoming better known in eastern European countries and in the USA, where they became recognised, as the breed of Caucasian Mountain Dog, by the United Kennel Club in 1995.

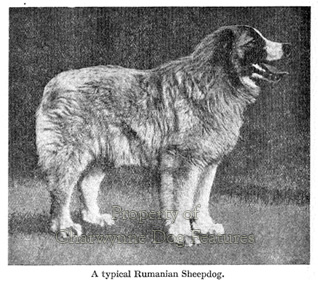

If you lined up a Caucasian Owtcharka, a Carpathian Shepherd, a Karst, a Sarplaninac, a Spanish Mastiff, an Estrela Mountain Dog, an Anatolian Shepherd Dog and a Tibetan Mastiff, in a brindle or wolf-grey coat, you could soon see how function decided form in such breeds, as well as how very similar in type they are. This, despite the immense distance from the Atlantic in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east. If you lined up parti-coloured specimens of the Rafeiro do Alentejo from Portugal, the Pyrenean Mastiff, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, the Anatolian Shepherd Dog, the Mioritic Shepherd and the Bucovina Shepherd of Roumania, again the similarities would be startling. To do their work as flock guardians, mountain dogs or steppe dogs have to have thick, weatherproof coats, size and substance, great stamina and robustness and a strongly-developed protective instinct. Making use of this natural guarding instinct, the owtcharka type has been crossed with a St Bernard to produce the Moscow Guard Dog, a huge imposing protection dog, now becoming favoured in Russia.

The Central Asian Owtcharka needs less coat but all the other attributes to do its work. The breed is found from the east of the Urals to areas of Siberia and south into Mongolia. The best examples today tend to be in Turkmenistan, where it has been recognised as 'a national treasure'; they can also be encountered in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Their coats are shorter, but their skin is thicker than the other owtcharka breeds, and their ears and tails are normally cropped. They remind me of a smooth St Bernard. They resemble too the bigger forms of shepherd's dog once depicted here, when used in times past as a shepherd's mastiff or flock guardian. The Central Asian is is a powerful breed, having been used as a hunting dog on boar and bear because of its bravery and dash. Those with tan markings over their eyebrows have been dubbed the 'four eyed Mongolian Dogs'.

The third owcharka breed is the South Russian, white, off-white or grey, long-haired, over 30 inches at the shoulder and weighing around 75 kgs. They remind me a little of the early depictions of our Old English Sheepdog, as portrayed by Reinagle for example. They are similar to the Hungarian Komondor, without that coat texture, being used, like the latter, on the steppes, only in their case in the Ukraine. This south Russian breed is not one to be trifled with; it is known as 'the white giant' in some areas of its homeland and is often harshly treated. There is an old Russian saying that states that a 'pampered South Russian is a killer'! The military have found uses for them but their export is not encouraged. Despite their reputation for 'hair-trigger aggression', you have to admire a breed that can survive such a hard climate, such fearsome predators and stern handlers, over many centuries. Their aggression may have been the key to their survival.

Innate protectiveness in dogs does bring with it intense loyalty, as owners of dogs from the flock guarding breeds will know. I was not surprised to learn of the Caucasian Owtcharka, left behind when deposed leader Aslan Abashidze was recently exiled from Adzharia in western Georgia, being reunited with his owner in Moscow after his excessive pining moved all who witnessed it. Abashidze, for all his faults, has been credited with saving this breed from extinction. He was said to have had around 80 of the breed, subsequently auctioned off by the Georgian dog breeders' federation. The breed is reported to have guarded the Soviet side of the Berlin Wall.

Their sheer size and immediate suspicion of strangers has led to their employment as guard dogs within Russia. I believe it is incorrect to describe such a breed as aggressive; the flock guarding breeds are overtly protective, of their owners and his property, a most valuable instinct for shepherds and drovers to utilise.

Kohl, in his Journeys in South Russia of 1842, when describing the shepherds there and their dogs, wrote: "The shepherds make their evening meal round a blazing fire, with their twenty watchful dogs encircling them...Between every two shepherds three or four dogs are placed, also at equal distances from each other. In order to make the dogs stay on their respective posts, a piece of an old cloak or sheepskin is laid on the spot...as each knows his own, he is sure to lie down wherever he finds it." Kohl visited Scotland around 1844 and described a drover's dog seen there as a 'wild, shaggy wolf-dog'. Such a dog was often described as a shepherd's mastiff.

In his Researches into the History of the British Dog of 1866, George Jesse quotes a Mrs Atkinson as saying of the flock guardian of Tartary she saw near Omsk in West Siberia: "As I looked at her I thought I never saw anything more beautiful; she was a steppe dog; her coat was jet black, ears long and pendant, her tail long and bushy; indeed, it was a princely animal." All over Tartary too, these huge flock guarding breeds were valued. One old saying there stating that: "To ask an Usbek to sell his wife would be no affront, but to ask him to sell his dog, an unpardonable insult". Not a very modern view!

The Hungarian pastoral breeds, with the exception of the unique Puli, mirror the form of other nation’s dogs: the Kuvasz resembles the Tatra and Pyrenean Mountain Dogs, the Komondor has a distinct Bergamasco type to it, the Mudi resembles the spitz herders and the Pumi looks like a Labrit, as function influences form. In their book Dogs of Hungary of 1977, Sarkany and Ocsag write: “The nomadic shepherds were always aware of the value of a good working companion: they kept two types of dog, the big white guard dogs who took over the flock at night, and the small active sheep dog, the Puli, who actually worked the flock by day. The shepherds protected the characteristics of their dogs by taking care that the two types did not cross-breed, and by ruthlessly culling out weak specimens.” They went on to point out that sheepdogs had to endure great extremes of temperature, variations of over 40 degrees C between summer and winter, with wind chill adding to the challenge. The two quite different big white flock guarding breeds were favoured in the same country, grazing areas being rather different where each was patronized. The Kuvasz was kept in the mountainous areas, sometimes in what were termed white villages, where only white livestock protection dogs were tolerated. The Polish Kuvasz-equivalent is in the Tatra Mountain pastures, (with their Lowland Sheepdog equating with the Puli), and the Slovakian Kuvasz in the higher Carpathians and the Carpathian Sheepdog claimed by Roumania. The Komondor was very much the steppe flock guardian of Hungary. The movement of sheep from pasture to pasture has rarely observed national borders.

Perhaps we should admire them from afar, all these powerful livestock protection breeds would find urban living in western countries intolerable. When I see such highly protective dogs at foreign shows, usually securely muzzled and justifiably so, I ponder the provisions of our foolish Dangerous Dogs Act. We are not free to import breeds like the Fila Brasileiro, the Tosa and the Dogo Argentino. When I see them at overseas shows they behave immaculately, both with people and other dogs. Their owners shake their heads in disbelief when I tell them of our law-makers. Our global reputation for common sense, moderation and an enlightened attitude to animals has been undermined. Foreign breeds renowned for their overt protectiveness, like the owtcharkas, can paradoxically but rightly enter our country freely. I am strongly against breed-specific legislation; the law as it stands protects nobody. Dogs of every breed can be successfully socialized; any individual dog of any breed can transgress if not adequately socialized. But it is asking a great deal to expect a big free-ranging highly-independent dog from a remote part of the world to become, overnight, an urban pet. We have to respect their heritage ahead of our selfish desires.

Big naturally-protective sheepdogs like the owtcharkas of Russia, the Kuvasz breeds of Hungary, Slovakia and Poland and the spaghetti-coated Komondor have long served the shepherds of the steppes and been greatly valued by them. Now, in the New World, their value is being recognised too. It is a rich heritage and one to be treasured. Brave determined protective dogs in any country deserve our admiration. The Tibetan Mastiff has been bred down to be an acceptable companion dog in the developed countries; most mountain dogs are best left where they belong. There is one breed that brings the best of this type of dog to our more crowded world - the Leonberger of today, created in the flock guardian mould. It may never have carried out this timeless role but for me this impressive breed epitomises both the character and the stature of such admirable selfless dogs - gentle giants of imposing grandeur, forever ready to serve.