1049 DOGS IN TRANSIT- TRADING PLACES

DOGS IN TRANSIT - TRADING PLACES

by David Hancock

The transportation of dogs has become easier and easier, with long-distant sea-travel, an extensive railway network and ever-improving air travel allowing the freer passage of dogs between countries and regions of countries. The means of conveying them has improved markedly too, both in road-movement more locally but in air-movement especially. This has not always been to the benefit of dogs; the recent annual 'rescue' of 20,000 abandoned dogs from Rumania to Britain has hardly helped our own self-inflicted problem of 300,000 unwanted dogs in our dogs' homes. The importation too of exotic breeds, only for that breed not to 'catch-on', can weaken a gene pool and spoil breed 'type'. Breeds like the Labrador and the Newfoundland prospered because of ship's movements. Breeds in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, sometimes mistakenly dubbed native breeds, can be British breeds relocated. The English Channel has witnessed the passage of dogs, scenthounds in particular, for centuries, as has the sea-lanes of the Mediterranean, for the sighthound breeds, and across the Bering Sea for the sled-hauliers. Whole packs of Foxhounds have been exported from Britain, as the fairly recent sale of the famous Dumfriesshire pack exemplifies. It is likely that the Alaunt type was brought into Europe by the cavalry of the invading Romans, recruited from the Steppes and the Caspian Sea area. But dog-trading has not always been conducted to the betterment of dogs themselves.

Dog-traders have earned themselves a somewhat dodgy reputation in modern times, but trading in dogs in past times allowed the widespread movement of dogs and a wider appreciation of their usefulness. Dogs accompanied wandering tribes, campaigning armies and migrating peoples, provided they had some use. The game-catchers like the sighthound breeds, the game-finders like the modern gundog breeds and the flock-guarding breeds each had a distinct value to man. The need to control vermin led to the development of the terrier breeds. The need to control sheep gave us the herding breeds. Dogs that excelled in their specialist function have long been traded but not always wisely or honorably. Dog-welfare measures need to cover breed-welfare issues too. The particular function of each dog not surprisingly led to the development of the physique that allowed the dog to excel in that function. That is why sighthounds have a muscular light-boned build, the terriers a low-to-ground anatomy and the flock guardians substantial size.

Sighthound breeds, wherever they were developed, project the same silhouette, display the same racy phenotype. The Azawakh of Mali, the Harehound of Circassia, the Sloughi of Morocco, the Magyar Agar of Hungary and the Tasy or Taigon from Mid-Asia would never change hands if they didn't look like fast-running dogs. If they didn't possess this anatomical design they couldn't function as speedsters. Hunters and sportsmen the world over know that the ability to catch game using speed demanded a very distinctive build. The sighthounds bound; they must have the height/weight ratio, the leg length and the liver-size to sprint. Sighthounds race entirely on liver glycogen, sugar activated from the liver. Sprinting demands long legs and a sizeable liver. The bigger the liver the more sugar can be stored. A sighthound over 65lbs in weight would have a problem through heat storage; their streamlined build allows a greater surface area. We are good at getting rid of excess heat and not very good at storing it. Dogs are the reverse, removing excess heat from their surfaces rather as a radiator gives off heat.

When sighthounds were traded, these technicalities were not known but the radiator-like build, size without weight and long legs meant something to their traders. The most successful sprinters had the build to succeed and were traded and perpetuated. In breeding for appearance only we need to bear in mind those anatomical essentials which made sighthounds what they are: internationally renowned sprinters. An 85lb Borzoi will experience difficulties when running flat out; a Greyhound of any weight with a small liver will have an even bigger handicap. Traders in such hounds couldn't measure livers but they could measure performance.

Similar but more perceptible criteria affect the flock guardian breeds. It is forgiveable to believe that such breeds are sizeable because they need to be able to see off wild animals which prey on sheep. But much more important are the bigger stride afforded by size, the ability to carry more fat reserves and store more heat than a small dog and to survive disease, severe weather and the odd accident - big bones break less easily than tiny ones. This is why such breeds possess a similar phenotype; the Sarplanninac (from Macedonia) is easily confused with a Slovenian Karst or a Caucasian Owtcharka, or a Maremma (from Italy) with a Pyrenean, a Tatra Mountain Dog (from Poland) or a Hungarian or Slovak Kuvasz. The traders in such dogs knew what made a dog effective and therefore more valuable. Flocks could be traded across national boundaries, as the long-distance sheep-driving (transhumance) routes across the Balkan countries illustrate.

Traders in sled dogs made comparable judgements from their experiences. They learned to value economy of motion in their dogs; their gait leading to success, a smooth motion in which their feet hardly leave the ground. The top racing teams cover a mile in just over 3 minutes nowadays. This capability is rooted in the size:weight ratio. The dogs pull by pushing forward and the heavier the dog the greater the energy required to do so. A 50lb Alaskan hybrid husky has evolved as the optimum sled dog. Of course such a dog has to have the right feet, coat and constitution to support its work, but the relationship between height and weight is the key. The physique of each 'husky' breed varies according to its employment and the 'going' of its deployment. No doubt the show ring will dictate that sled dogs one day will be mainly valued for their coats, flock guardians for their size alone and the sighthound breeds for their sheer skinniness. They will be traded on cosmetic grounds alone and as breeds, not functional creatures based on demanding criteria. This will please the kennel clubs of the world and make veterinary surgeons richer but will not do much for dogs. There is a wanton disregard for hybrid vigour amongst dog breeders and contemporary dog traders have learned that the closed gene pool in recognised breeds has to be respected for commercial success. Breed specific diseases are often ignored, despite the noble efforts of a few. Who has examined the genotype of the Peruvian Inca Orchid Dog or the Mexican Hairless Dog before their importation?

Importing a breed you have admired on an overseas trip or on misguided whim is more self-indulgence than breed welfare. Their early recognition by the KC is greed ahead of need. Of the KC-registered gundog breeds, the Small Munsterlander attracted 1 registration in 2016, the American Water Spaniel zero. What is value of that to those breeds? In the Hound Group, no Segugio Italiano, Sloughi, 1 Grand Bleu de Gascogne, Griffon Fauve de Bretagne and Ibizan Hound and in the Pastoral Group 0 Bergamasco, Kuvasz and Swedish Lapphund were registered. In other groups, 0 Pyrenean Mastiffs, 2 Canaan Dogs and 6 Korean Jindos were registered. What truly is the value, to these breeds, of such figures and example? How irresponsible it can be to drag dogs half way round the world only to waste breeding material best utilised closer to home. Before we start saving foreign breeds, however well-intentioned, we really must confront the problem of our own over-full rescue centres and endangered native breeds. It has become just too easy to import a dog.

I feel immense sympathy for responsible breeders of pure-bred dogs in Britain. Unlike mainland Europe our breed clubs have no muscle and little say in the health, breeding rates and rescue systems in their particular breed, If pedigree dogs were registered through their breed club only, a very different scene would emerge. If breeding stock were to be subject to mandatory health clearances, a totally different type of breeder would emerge. At present the written pedigree tells you more about the breeder than the dog! A dog came Best-of-Breed at Crufts a few years ago when it had been bred from 59 mainly-unrelated ancestors out of a possible 62 on a 5-generation pedigree. Bizarrely, this dog became a sought-after sire! This is not perpetuating a breed to a set plan, just firing a genetic scattergun!

What ever happened to line-breeding! How can any dam's owner put a bitch to such a mish-mash of genes? And yet, the bitches in that breed queued up for a service from the Crufts winner. We can no longer judge so many breeds on their usefulness, but surely that puts even greater emphasis on type and soundness. You only have to read the judges' critiques to see that in some breeds we are in danger of losing both. But what can a knowledgeable honourable breeder do in the current free for all? It costs money to have your stock health-screened, to rescue any displaced pups from your own breeding, to travel to the sire best suited for your line and to keep up with the latest research on your breed. And, when you have financed all these things, you look in a weekly paper to discover that a breeder who has done none of these things is selling, and registering, pups as if there's no tomorrow. Have we really progressed in Britain from the Victorian street markets for dogs? We seem obsessed by the written pedigree and seem to regard it as some sort of kitemark. The man in the street is gradually seeing through this deceit and, with The Sale of Goods and The Trades' Descriptions Acts, taking action increasingly when metaphorically 'sold a pup'. And that expression didn't come into common usage without reason!

There's a great deal to be done if the world of the pure-bred dog isn't going to lose credibility, slowly but irretrievably. Most purchasers of pedigree dogs are pet-owners; all they want is a dog which lives a long and active life and costs little at the vets. Sadly, in far too many breeds, they are being offered a dog bred purely for appearance without regard for its genetic health, not always adequately socialized and increasingly short-lived. Dogs of virtually unknown genetic health and unverifiable breeding are imported, merely because they are registered with an associate kennel club. Half a century ago, I saw some heavily wrinkled pups in a Hong Kong street market; their eyes were sore and their general condition pitiful. One was literally tail-less. The local police referred to them as 'Chinese Boxers', regarded them as dogs bred for fighting and stated that they were usually imported, from the mainland, Taiwan or Macao. I was disturbed to discover ten years later that such dogs were being imported into the United States - as a valuable Chinese rare breed that 'must be saved'. Now we have the Chinese Shar Pei on parade at Crufts and, to be fair, the British breeders do seem to have improved this breed here.

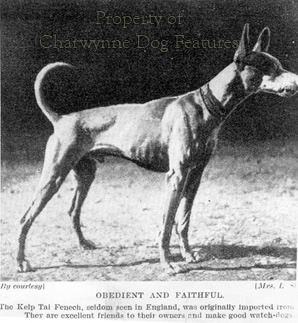

It does seem odd to me that a breed from such a background can be recognised and registered with our KC when Salukis bred by Arab sportsmen for several centuries on known breeding are declined registration, ostensibly because of a lack of written breeding records. Yet false provenances for foreign breeds are accepted here. I was once solemnly told by a Pharaoh Hound owner that his breed was prized by the Pharaohs and subsequently pure-bred on Malta and Gozo over two thousand years of isolation. And he believed it. When I was based in Malta half a century ago, we used to go rabbit hunting with the local farmers on Gozo and the Mellieha peninsula. They had small bat-eared sighthounds in packs of half-a-dozen, lithe, quick-witted, skilful hounds. In these packs was a red-tan Whippet left behind by a naval officer and a whole tan Manchester Terrier, both prized as breeding material because they introduced outside blood. The local farmers called them Kelb-tal-Fennec - rabbit-dogs; not one person there referred to these hounds as Pharaoh Hounds, considered them to be pure-bred or even unusual for the Mediterranean littoral. And of course they are not; there are podencos of this type in the Iberian coastal areas and in the Balearics; there are hounds exactly like this in Sicily and Crete. To invent a false provenance for any breed insults the real heritage of that breed.

Is the Bloodhound a British breed or a Belgian one? Is the Newfoundland a British breed or a Canadian one? Is the Australian Shepherd Dog not just our Border Collie relocated? Is the Dogue de Bordeaux not likely to be an English mastiff from the English long-time presence there? But identity apart, trading in purebred dogs over the last one hundred years has one particularly unfortunate feature: it is conducted on the basis of closed gene pools. The new breeds introduced do not bring new blood to old breeds. The dilemma for the next century is how to trade in healthier dogs - perhaps ahead of breeds.