1027 NOBLESSE OBLIGE - NOT ANY MORE

NOBLESSE OBLIGE? NOT ANY MORE!

by David Hancock

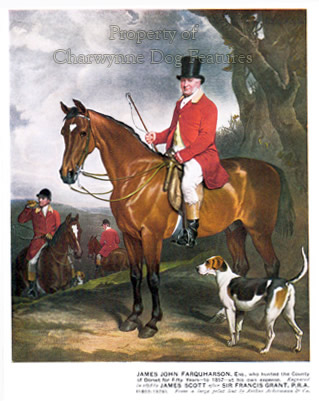

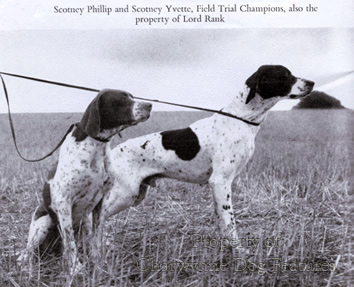

The nobility and landed gentry, before, during and just after Victorian times had a huge influence on dogs in Britain, sporting breeds especially. There were 200 packs of Foxhounds, with the Duke of Beaufort and Lords Donerail, Portsmouth, Coventry and Bentinck, Sir William Curre, as well as prominent squires like Osbaldson, taking a keen interest. The Dukes of Gordon and of Richmond kept Deerhounds, as did Lords Seaforth, Tankerville and Bentinck. Lord Bagot showed Bloodhounds and Lord Wolverton ran a pack of them in Dorset, later sold to Lord Carrington in Buckinghamshire. The Marquis of Anglesea kept Harriers and Sir John Heathcote-Amory favoured Staghounds. Lord Lurgan's coursing Greyhound Master McGrath won 3 Waterloo Cups out of 4. The Duke of Atholl maintained a pack of Otterhounds. The Duke of Montrose, Lord Rank and Colonel Thornton promoted the Pointer. In Borzois, the Duchess of Newcastle promoted them and the Duchess of Manchester owned a huge specimen bred by Prince William of Prussia. The president of the KC was a duke, as was his vice.

The nobility and landed gentry, before, during and just after Victorian times had a huge influence on dogs in Britain, sporting breeds especially. There were 200 packs of Foxhounds, with the Duke of Beaufort and Lords Donerail, Portsmouth, Coventry and Bentinck, Sir William Curre, as well as prominent squires like Osbaldson, taking a keen interest. The Dukes of Gordon and of Richmond kept Deerhounds, as did Lords Seaforth, Tankerville and Bentinck. Lord Bagot showed Bloodhounds and Lord Wolverton ran a pack of them in Dorset, later sold to Lord Carrington in Buckinghamshire. The Marquis of Anglesea kept Harriers and Sir John Heathcote-Amory favoured Staghounds. Lord Lurgan's coursing Greyhound Master McGrath won 3 Waterloo Cups out of 4. The Duke of Atholl maintained a pack of Otterhounds. The Duke of Montrose, Lord Rank and Colonel Thornton promoted the Pointer. In Borzois, the Duchess of Newcastle promoted them and the Duchess of Manchester owned a huge specimen bred by Prince William of Prussia. The president of the KC was a duke, as was his vice.

In the non-sporting breeds, Lady Alexander favoured Collies, as did Princess de Montglyon. Lady Lewis and Lady Pilkington were members of the Bulldog Club, Lady Brassey is said to have introduced the black Pug to us. More famous in the Pug world were Lady Willoughby de Eresby and Lady Reid. The Duchess of Richmond promoted the Pekingese, with the 'Japanese Spaniels' drawing the support of the Countess of Malmesbury, Lady de Ramsey, Countess Wharncliff, Lady Probyn and the Countess of Warwick. Princess Sophie Duleep-Singh bred quality black Poms. The Mastiff was kept by the Earl of Oxford, the Marquis of Hertford and Lords Stanley and Waldegrave. In the terrier world, the Countess of Aberdeen patronised the Skye Terrier and the Duchess of Newcastle the Fox Terrier.

Stonehenge in his Dogs of the British Islands of 1872, wrote that “The mighty dogs which used to be kept at Chatsworth were pure Alpine Mastiffs...” (by the Duke of Devonshire). The association between large and often imposing houses and large and equally imposing dogs is a long and varied one. In the days when the nobility of Europe prided themselves on their horses and dogs, many famous breeds owed their origin to the dedicated, almost single-minded patronage of landed families. The royalty and aristocracy of Europe liked to have their portraits painted with their mastiff-like dogs, as the Batoni portrait of Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh, the Della portrait of Kaiser Ferdinand II, the Van Dyck portrait of the children of Charles I and the Velazquez painting of Las Meninas illustrate, the latter featuring a cropped-eared Spanish Mastiff, a breed still existing today. The inherited sense of sporting history in the blood of such dynasties so often led to the stables and kennels being a prized feature of the family property. The architectural importance of purpose-built kennels such as those at Croxteth Hall in Liverpool and Lyme Hall near Manchester is now acknowledged. The fact that so many of these kennels no longer have dogs in them is disappointing.

Lyme Hall retains paintings of its mastiffs; Chatsworth and Nostell Priory retain the collars of their mastiffs. But how comforting it would be to see this ancient association revived, but not much chance of that today. Mastiffs, eminent owners and historic houses coincide again and again when the development of today's Mastiff breed is researched. We can read of the Earl of Oxford's 'Lion', the Marquis of Hertford's 'Pluto', Lord Waldegrave's 'Turk' and 'Couchez', Sir Fermor Hesketh's 'Nero', Sir George Armitage's 'Tiger' and Sir E Wilmott's 'Lion'. As well as the celebrated Lyme Hall strain, we can discover an old line of pure Alpine mastiffs (probably smooth St Bernards) at Chatsworth and references to mastiffs at Elvaston Castle near Derby, Hadzor Hall near Worcester, Trentham Park near Stoke on Trent, Bold Hall in Lancashire, Esthwaite Hall in the Lake District and Nostell Priory in Yorkshire, Lord Stanley's dogs at Alderley and Athrington Hall's 'Lion'. Mastiffs and mansions were clearly closely associated and those at Lyme Hall hardly unique.

I suspect that the separation of noble families from their mastiffs had multiple causes, with two world wars significant accelerators. But one rather sad reason could lie in the departure of the modern breed away from its historic mould as a heavy hound, used to pull down big game such as auroch, buffalo, boar and wild bull, and into a cumbersome unathletic overweight yard-dog. It is not historically correct to seek in this modern breed a dog weighing 180lbs, measuring 32" at the withers and lacking mobility, physical soundness, featuring sunken eyes and sagging lips. Morally, it is disgraceful to breed dogs with harmful exaggerations. Commercially, it is disastrous to breed dogs which attract huge veterinary bills. Compassionately, it is distressing to see dogs bred which only enjoy a limited lifespan and a restricted lifestyle. On these grounds I can understand any potential Mastiff owner, mansion-owner or not, looking elsewhere.

Nevertheless, the Mastiff, a magnificent breed of imposing stature and impressive temperament, is an important feature of our canine heritage and it would be good to see a remodelled breed, physically respecting its own ancestry, gracing the steps of great houses once again. Earlier this century, the Marquess of Londonderry and the Duke of Gloucester favoured the Bullmastiff, smaller and more athletic than their sister breed but strangely now being desired by some fanciers to be more mastiff-like. Fashion has destroyed more than one breed of dog but it would be good to see the Mastiff of England fashionable once again amongst mansion-owners. This is a breed of reassuring solidity, with noble bearing, an air of relaxed superiority yet possessing considerable reliability. They have much in common with the great houses they once adorned. Frank Townend Barton, MRCVS, in his 'Non-Sporting Dogs' of 1905, was thinking wishfully however when he wrote: "Many recent winners have been somewhat of the degenerate type, but at the present time a reaction is setting in with a view to a revival of the grand old type of English Mastiff. This is as it should be, and there can be no doubt that these monarchs of strength and beauty will again become fashionable and find places in the stately halls of Great Britain and her dominions."

The noble families made a significant contribution to the gundog breeds: Lord Tweedmouth in Golden Retrievers, the Earl of Malmesbury and Lord Knutsford in Labradors, Viscount Melville in Curly-coats, the Earls of Sefton, Lichfield and of Derby in Pointers, the Duke of Gordon in his type of setters, the Earl of Tankerville and Lord Waterpark in English Setters and the Duke of Newcastle, Lords Middleton and Spencer in Clumbers, and the Bowes family in Yellow Labradors. This is an impressive list but a very noticeable difference between the patronage of breeds of dog in Victorian times and now, is the almost negligible involvement of the nobility nowadays. Once, their interest guaranteed support for many breeds, a higher profile for the Kennel Club and the promotion of dogs for their sake rather than the bank balance.

Royal patronage led to a number of breeds becoming either known for the first time or more widely favoured. Victoria ascended the throne at the tender age of 18 in 1837, her much-adored dog 'Dash', a Toy Spaniel, then being her devoted companion. After her Coronation, it was alleged that she hurried home to bath him. She was to favour and own several other breeds: Dachshunds, Skye Terriers, Scottish Terriers, Pomeranians, Pugs, Maltese and Collies. One of her Collies, Squire, was white, not a recognised colour in the breed today. Queen Victoria entered the initial Crufts dog show in 1891, with six Pomeranians, each weighing around 30lbs! She had kennels built at Sandringham to house 60 hounds, the present Queen's Labradors being housed there today. Her heir, Edward VII, continued the family interest in dogs; he showed Chows, Skye Terriers and Basset Hounds, Queen Alexandra favouring Borzois and 'Japanese Spaniels' too. Edward's funeral procession was led by his close companion Caesar, a Fox Terrier. The Royal Family's dedicated interest in dogs undoubtedly affected public attitudes both to dogs and to the breeds they favoured, in the second half of the nineteenth century. For Crufts in 1893, the Czar of Russia sent over a splendid team of 18 Borzois, from his hunting kennels.

The long reign of Queen Victoria witnessed huge changes to Britain and the world and the world of dogs was no exception, undergoing changes with far-reaching implications. Britain had a wide reputation as a breeder of livestock; the existence of Empire ensured that British sporting styles and social trends soon spread all over the globe. When, in the days before quarantine, British landed gentry went on sporting tours, their dogs went with them. When British livestock was exported, the herding dogs went too. When the British emigrated or went to work for extended periods in places like India, their dogs went with them. In the second half of the nineteenth century British dogs became known in most parts of the world.

This widening influence was accompanied by changes at home; dog shows became fashionable, field trials were introduced and both hunting and shooting became 'must-do' events in the countryside. Shows and trials brought a need for registration so that a dog's identity could be verified. As the range and frequency of shot increased so the needs of sportsmen in their supporting dogs changed too. In the hunting field the better breeding of hounds received much more attention. Companion dogs too were influenced by greater foreign travel and the subsequent introduction here of exotic breeds from distant places. At the same time came more focus on animal welfare, the moral repugnance towards some barbaric so-called 'sports', greater concern over the plight of street-dogs, draught-dogs especially, and a move towards more enlightened training and less 'breaking' of dogs. Royal patronage and the obsession of the nobility with field sports gave some types of dog a higher profile. But the desire to produce dogs which closely resembled their parents and bred true to type, a fall-out of the show ring, led to the production of pure breeds. Of course, before that, breed-type was established in some cases with Greyhounds, Beagles, Pointers and Deerhounds usually looking like their ancestors. But from now on closed gene pools were to be respected and purity of breeding revered. For the first time in dog-dom, it wasn't just a case of breeding good dog to good dog, both parents had to be registered and out-crossing was frowned upon.

This development has had a marked effect on the well-being of the dog. Breeding from a closed gene pool is fine when things are going well but disastrous when inbred faults and genetic flaws are encountered. The Victorian era, quite often led by the nobility, may have given us the breeds but it has also given us the problems arising from in-breeding, conducted for a century in some cases. Our lives have been enriched by the breeds of dog handed down to us by our Victorian ancestors; now we must use scientific advances and increased veterinary knowledge to capitalise on and not be penalised by the admirable pioneering work done by the noble Victorians. This is the challenge for the newly-launched century, if one unlikely to be met. I do not know of one breed of dog in Britain today that is seriously promoted by one of the noble families. There might be ownership but who is keeping our sporting traditions alive and our breeds of dog honest? It would be good to witness not noble intentions but noble activity; being born into a noble family used to carry with it noble responsibilities. Noblesse oblige? Not any more!