1022 OUR MASTIFF FROM BORDEAUX

OUR MASTIFF FROM BORDEAUX

by David Hancock

Some years ago, I was challenged by a Dutch breeder of Dogues de Bordeaux over the origin of his breed. He maintained that it was of entirely English origin, stating: "The English were in Bordeaux for as long as the Romans were in Britain, and, whilst lots of spurious claims are made of the Romans introducing types of dog into Britain, no one points out the English-Bordeaux significance for my breed". And when you read Hugh Dalziel's 'British Dogs' (Vol II) of 1888, you can find this statement: "From this period there is ample evidence of the dissemination of this breed of dogs (i.e. Bulldogs) over the Continent; and this was much assisted by the fact of so important a town as Bordeaux having been in the hands of the English from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, and the court of King Edward, with its attendant English sports of bull and bear baiting, having been held there for about eleven years." My Dutch colleague's theory has some basis; the Dogue de Bordeaux could justifiably be called in Britain 'our mastiff from Bordeaux'. That will enrage many!

Some years ago, I was challenged by a Dutch breeder of Dogues de Bordeaux over the origin of his breed. He maintained that it was of entirely English origin, stating: "The English were in Bordeaux for as long as the Romans were in Britain, and, whilst lots of spurious claims are made of the Romans introducing types of dog into Britain, no one points out the English-Bordeaux significance for my breed". And when you read Hugh Dalziel's 'British Dogs' (Vol II) of 1888, you can find this statement: "From this period there is ample evidence of the dissemination of this breed of dogs (i.e. Bulldogs) over the Continent; and this was much assisted by the fact of so important a town as Bordeaux having been in the hands of the English from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, and the court of King Edward, with its attendant English sports of bull and bear baiting, having been held there for about eleven years." My Dutch colleague's theory has some basis; the Dogue de Bordeaux could justifiably be called in Britain 'our mastiff from Bordeaux'. That will enrage many! at a Paris show.jpg)

A thousand years ago, the most famous heavy hound in Central Europe was the famed Englische Dogge or English Mastiff (dogge, or dogue, meaning mastiff). The Deutsche Dogge or German Mastiff, now the Great Dane or Dogue Allemand, came in its wake, although the expression Dogue Danois was also used in France. In his 'The French Royal Hunting Accounts' of 1398, Philippe de Courguilleroy, Master Huntsman to the King, wrote: "Guillot le Mastinier, called Sonot, for his expenses in the Forest of Dyrmon in seeking 24 mastiffs borrowed for the King's sport in his boar-hunting in the Forest of Halatte, and for his lodging for this purpose and for bringing these mastiffs to the Forest with the boar-hounds for ten days..." He made a difference between mastiffs and boarhounds and stressed their value. To this day, the boar is hunted in France using packs of scenthounds rather like our Staghounds..jpg)

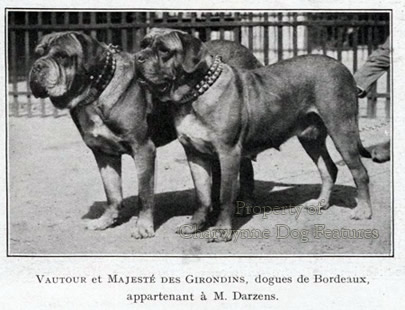

There are plenty of depictions of 'French Mastiffs' (Dogues Francais were shown in Paris a century ago) showing powerful seizers of very substantial construction. The French catch-dog, the Dogue de Bordeaux of today, hardly lacks substance. But I do see too many cloddy specimens, low-set, over-dewlapped and coarse in the neck and shoulders. This type seem to feature too an undesirable 'Chippendale' front, in which the front legs bend in at the pasterns then out again in the feet. Yet this breed has one of the best written breed standards I have ever read. Its list of faults, especially disqualifying faults, gives clear unambiguous guidance to ju dges and should be a model for the other modified brachycephalic breeds. I like the phrase under 'general appearance' which requires: "a very muscular body yet retaining a harmonious general outline." Shown at the first French dog show in Paris in 1863, the breed once had three types: the Toulouse (which showed signs of Spanish influence), the Paris and the Bordeaux type (linked with the wine trade and the dogs of the countries trading e.g. England), which prevailed. The breed was imported into England in the 1890s by two Bulldog fanciers, Woodiwiss and Brooke. Woodiwiss purchased a fighting dog, scarred from combat with bears as well as dogs. Not to be outdone, Brooke imported from Bordeaux itself a fawn dog, with immediate ancestors that had tackled wolf, bear and hyena, one being killed in San Francisco whilst taking on a jaguar. Brooke tried his dog at a large Russian bear which stood six feet high when up on its hind legs. The account of this contest stated that: "The dog showed great science in keeping his body as much sideways as possible, to avoid the bear's hug, and threw the bear fairly and squarely on the grass three times."

dges and should be a model for the other modified brachycephalic breeds. I like the phrase under 'general appearance' which requires: "a very muscular body yet retaining a harmonious general outline." Shown at the first French dog show in Paris in 1863, the breed once had three types: the Toulouse (which showed signs of Spanish influence), the Paris and the Bordeaux type (linked with the wine trade and the dogs of the countries trading e.g. England), which prevailed. The breed was imported into England in the 1890s by two Bulldog fanciers, Woodiwiss and Brooke. Woodiwiss purchased a fighting dog, scarred from combat with bears as well as dogs. Not to be outdone, Brooke imported from Bordeaux itself a fawn dog, with immediate ancestors that had tackled wolf, bear and hyena, one being killed in San Francisco whilst taking on a jaguar. Brooke tried his dog at a large Russian bear which stood six feet high when up on its hind legs. The account of this contest stated that: "The dog showed great science in keeping his body as much sideways as possible, to avoid the bear's hug, and threw the bear fairly and squarely on the grass three times."

I like bears too much to approve of such a contest but the enormous strength and determination of the dog has to be of note. The Kennel Club's anti-earcropping regulation dampened the enthusiasm of these early British fanciers however, with both Woodiwiss and Brooke selling their dogs to a Canadian who exported them. Now the breed is gaining favour in Britain once again, attaining KC recognition in 1997 and now fielding two breed clubs and attracting growing support. Britain does not however have an entirely admirable record in breeding its own mastiff breeds soundly and in their correct historical mould. I do hope this breed doesn't end up as a caricature of itself, as some Bulldogs and Mastiffs sadly do. At the end of the Second World War only 4 specimens remained in France; in 2010 nearly 3,000 were registered in Britain alone. There is a strong need for breeders to research their stock diligently if the predictable end-results of too-close breeding start to manifest themselves.

I believe that just before the Second World War, an English sportsman living in France kept a small pack of Dogue de Bordeaux to hunt boar. These would have been valuable breeding material but sadly did not survive the war. Powerful dogs bred unwisely, without skill, without regard for their heritage and with no concern over their health soon deteriorate and, like the St. Bernard and many Great Danes, become weak dogs, both in physical strength terms and in their resistance to disease. The Dogue de Bordeaux could very quickly become an anatomical disaster if its breeders do not keep to their agreed Breed Standard. This standard, drawn up by the highly experienced Raymond Triquet in France, makes many subtle but vital points. The feet should turn slightly outwards, the topline should show some dip, the stop should be pronounced, at an angle of 95-100 degrees to the muz zle, any wrinkles formed should be mobile not static, giving an elasticity to the skin, the loin is wide and strong but not long and there are three colour variations of the muzzle mask: black, chestnut and red, with the nose leather matching these shades. The chin should not protrude beyond the upper lip nor be covered by it. The lips should meet edge to edge at the front, with the thicker upper lip falling away to the sides, covering the lower lip. From the front, this fall-away should create a large, wide, inverted V. If rounded to inverted U-shape then a Bulldog look is obtained, if the V is too acute then a Neapolitan Mastiff look is displayed.

zle, any wrinkles formed should be mobile not static, giving an elasticity to the skin, the loin is wide and strong but not long and there are three colour variations of the muzzle mask: black, chestnut and red, with the nose leather matching these shades. The chin should not protrude beyond the upper lip nor be covered by it. The lips should meet edge to edge at the front, with the thicker upper lip falling away to the sides, covering the lower lip. From the front, this fall-away should create a large, wide, inverted V. If rounded to inverted U-shape then a Bulldog look is obtained, if the V is too acute then a Neapolitan Mastiff look is displayed.

As with all breeds of this type, the weight is on the forehand, with the centre of gravity well forward. This means that, on the move, the dog carries its head low - because it is designed to do so. Handlers in the show ring who strive to make the dog move with a high head carriage are inhibiting the natural gait/posture of the breed and judges must be alive to this. A Dogue de Bordeaux has been recorded with a neck of 70cms, weighing in at 75kgs. How on earth can a dog of such dimensions move with a high head carriage? This strange show ring insistence could one day reach back and influence the breeding programmes of the misinformed, with disastrous consequences for type in this breed.

This breed has had a remarkable rise in popularity in Britain in a relatively brief period of time. In 1994, 11 were registered; in 1998 it was 195; in 2001 - 661; in 2003 - 1,238; in 2009 - 2,790; over 2,000 each year for a few years, then over 1,700 in 2015 (against only 500 Bullmastiffs - our national equivalent). It would be very surprising if, in that space of time, quality matched quantity. I can see why the judge at the Three Counties Champions hip Show of 2011 wrote: "...because the breed has become so popular, indiscriminate breeding is taking place. Novice owners are mating their bitches to dogs that do not complement them and we are doubling up on faults - and we are beginning to see dogs with short upper arms, dippy toplines and rear-ends that are too high..." I see far too many specimens with over-wrinkled heads, short front legs, overlong backs and a distinct lack of athleticism. This breed has to have controlled power and give an impression of disciplined strength. The Crufts judge of the breed in 2013 wrote: "..although a heavy breed with a long low gait, they should be able to move around the ring more than a couple of times." The breeders of this distinctive breed must look at the fate of the Mastiff breed in the hands of show ring fanciers: the same dippy toplines, high rear-ends, over-wrinkled heads, short front legs and, arguably worst of all, a complete lack of athleticism. This distinctive breed deserves the best breeders - and watchful judges.

hip Show of 2011 wrote: "...because the breed has become so popular, indiscriminate breeding is taking place. Novice owners are mating their bitches to dogs that do not complement them and we are doubling up on faults - and we are beginning to see dogs with short upper arms, dippy toplines and rear-ends that are too high..." I see far too many specimens with over-wrinkled heads, short front legs, overlong backs and a distinct lack of athleticism. This breed has to have controlled power and give an impression of disciplined strength. The Crufts judge of the breed in 2013 wrote: "..although a heavy breed with a long low gait, they should be able to move around the ring more than a couple of times." The breeders of this distinctive breed must look at the fate of the Mastiff breed in the hands of show ring fanciers: the same dippy toplines, high rear-ends, over-wrinkled heads, short front legs and, arguably worst of all, a complete lack of athleticism. This distinctive breed deserves the best breeders - and watchful judges.

Sadly, this breed is among the shortest-lived and is one of the worst scoring breeds in the BVA hip score scheme; elbow problems and breathing difficulties from too fore-shortened a skull are all too common. One fifth of births have to be by Caesarean section. Excessive facial wrinkle can cause eczema, hot spots and sores, as well as eye disorders such as ectropian and cherry eye. The most common cause of death reported in the American breed survey was lymphosarcoma; but almost as common was heart disease, aortic stenosis in young dogs and cardiomyopathy in adults. From the health perspective alone, I dislike the excessively-wrinkled dogs and the pursuit of needlessly heavily-boned dogs. The red-fawn coat colour and brown-pigmented nose now seem standard but I have seen fine specimens with black noses. This reddish tinge has long been noted; in Jardine's Naturalists' Library Vol X of 1840, Hamilton Smith was writing: "In France, reddish dogs were still generally used to hunt the wolf to the year 1779...mostly of a rust colour, with black backs." The standard red-fawn coat of today is a preference whereas a century or two ago, red brindled and tan-fawn, black-masked dogues were also widely patronised. The Breed Standard allows all shades of fawn, from mahogany to Isabella, with a black mask permitted (but not encouraged!). If only red-fawn exhibits win prizes however the gene-pool will soon become impoverished - and that would be a pity for such an imposing breed.