1004 LIFE SKILLS FOR DOGS

LIFE SKILLS FOR DOGS

by David Hancock

Great play is made nowadays on the instillation of 'life skills' in young people to prepare them for the adult world and the workplace. But the preparation and education of dogs, for the world they are destined to live in, needs a comparable emphasis. And the time frame for such an education is relatively brief. The scientific evidence for the essential need to socialize the very young dog has been there for years without the dog owning and breeding world as a whole making full use of it. The researches of Scott and Fuller and the experiences of Pfaffenberger are well documented. In 1950, Scott published a paper establishing that the critical period for social development in a pup was roughly between two and sixteen weeks. During this time the pup learns its social skills; at sixteen weeks the social learning opportunity lapses. After that stage, the dog has very poor abilities to develop or adapt its social skills. That is why puppy-farmers are so bad for young dogs. Dogs need to learn life skills from a very early age.

Great play is made nowadays on the instillation of 'life skills' in young people to prepare them for the adult world and the workplace. But the preparation and education of dogs, for the world they are destined to live in, needs a comparable emphasis. And the time frame for such an education is relatively brief. The scientific evidence for the essential need to socialize the very young dog has been there for years without the dog owning and breeding world as a whole making full use of it. The researches of Scott and Fuller and the experiences of Pfaffenberger are well documented. In 1950, Scott published a paper establishing that the critical period for social development in a pup was roughly between two and sixteen weeks. During this time the pup learns its social skills; at sixteen weeks the social learning opportunity lapses. After that stage, the dog has very poor abilities to develop or adapt its social skills. That is why puppy-farmers are so bad for young dogs. Dogs need to learn life skills from a very early age.

Subsequent studies by Coppinger and Scott provided greater detail; they identified five crucial periods of puppy development. The first went from 1-3 weeks, with a need for mother, warmth, sleep, food and 'massage', an extremely limited mental capacity, little requirement for handling by humans, with the eyes opening at 10-14 days and the ears 'opening' in 13-17 days. The second went from 21-28 days, i.e. the 4th week, with the same continuing needs and some functional awareness, as the senses were now functioning. This was found to be one of the most critical periods in a puppy's life; socialization begins, the pup can see and hear, is vulnerable to unsettling influences and the introduction of other species, i.e. humans, other pets, and needing careful management. Dog-to-dog socialization is important.

The third period, 29-49 days or 5-7 weeks, brought new needs: canine socialization, within the litter, and human socialization, outside the litter. The pup now responds to human and canine sounds, can recognize individual humans, must learn to compete with litter mates and develops an awareness of the external world. Some of the most balanced dogs I have had were raised as pups in a kitchen, handled by the family when young and acquainted with the activity and noise of humans. The most nervous pups I have come across have been those raised in a distant kennel, away from human contact and sounds of the big world. A number of such dogs do adapt later to what they initially perceive as external threats, but fearful dogs are so much more difficult to train. Calmness and natural boldness are features to be encouraged.

The fourth period, 50-84 days or 8-12 weeks, is a highly sensitive time. The pup needs to be removed from the litter and the 24 hour maternal cover, to have love and security from a new authority figure, supervised play with humans and a degree of both exposure and protection. Malicious or accidental pain or painful experiences now leave lasting or permanent presence. Care is vital to prevent adverse conditioning. The pup's confidence must be progressively built up to produce a stable and reliable adult. The pup can now respond to gently imposed discipline, it has recordable electric brain wave activity. It can form permanent bonds with humans. It can be introduced to the function of its breed. The enjoyment of obedience can be nurtured.

The fifth period, 13-16 weeks or 85-112 days, brings needs of loving attention, gentle discipline, further exposure to the wide world and the provision of a feeling of security. The pup's mental capacity is fully developed, it is capable of learning through experience; its mind is still being influenced. The puppy is now willing to assert itself and achieve dominance, yet is still sensitive, needing guidance and a great deal of praise-filled encouragement. After this period, bonding, training, development along desired lines and the arousal of inherited instincts become increasingly difficult. Gentle control is easily achieved; steadiness can be spotted early and encouraged.

Scott concluded: "The evidence from puppies is that they have a short period early in life when positive social relationships are established with members of their kind and after which it becomes increasingly difficult or impossible to establish them. The same applies to their relationship with human companions. The period in puppies when we can best socialize them and begin their training is in the period of five weeks to twelve weeks of age." Pfaffenberger recorded that: "Socialization with human beings, by taking the puppy from its nest and giving it personal affection and some little training as early as five weeks of age, was found to be desirable." (If you want a truly difficult young animal to train, try the cat! they like to train us!)

Clarence Pfaffenberger was described by Scott as a man with the special gift of combining effective practical work with dogs with an appreciation of the value of basic scientific research. Pfaffenberger was assigned the task of finding the ideal puppy to develop into the ideal guide-dog for the blind at San Rafael, California. His experience was vast, his observations of immense value and his contribution to our knowledge today of rearing puppies simply huge. His book 'The New Knowledge of Dog Behavior' (Howell House, 1963) is a masterpiece. So many of the esteemed Victorian gundog trainers would have benefitted from his acquired wisdom. They used such expressions as 'breaking and entering', meaning schooling a gundog and a terrier into their future role. Puppies enter this world usually because we humans arrange such a matter. Puppies enter the big wide world on our terms; they reflect in some way the old Jesuit principle of 'give me a child of five and I will give you the man.' Every day on the streets it is possible to see inadequately 'entered' dogs. How dogs are 'broken' or 'entered' is as important as whether they are.

Mark Hayton of Ilkley, Yorkshire, sheepdog trainer supreme, once wrote: "It is not by the boot, the stick, the kennel and chain that a dog can be trained or made man's loyal friend, but only by love. For those who understand no explanation is needed; for those who do not, no explanation will prevail." That latter sentence is the crucial one; it is much more profound than it looks at first glance. The top sheepdogs always seem to have an almost magical relationship with their handler-owners. It is a true partnership with both dog and man having their brains engaged. The mere idea of a top class sheepdog being 'broken' is unthinkable. Inherited skills are vital in the sheepdog; the herding instinct is strongly passed on in a sheepdog litter - but this can be a mixed blessing when such strong instincts are not exercised or redirected.

In old films featuring sled-dog teams, you often see the driver of the sled lashing the dog-team with a long whip. But experienced sledders will tell you of the sheer foolishness of any such action. First of all there is never any need to force the sled-dogs to run fast, they love the whole business and are as keen as to pull as any dog could be. The skill lies in controlling and directing them, not bashing them. Secondly, an injured dog is a serious liability; and, thirdly, a cowed dog doesn't pull its weight. Whips, sadly, belong in the circus where animals perform unnaturally, not in driving eager dog teams. Books on training dogs a hundred years ago, especially on training dogs for the gun, often contained the word 'breaking' in their title. Some of the latter included such classics as: 'Dog Breaking' by General Hutchinson (1909), 'Dog Breaking' by 'Wildfowler' (1915) and 'Breaking and Training Dogs' by 'Pathfinder' and Dalziel, a little earlier. The trainer is called the breaker in such books and a trained dog is described as 'broken'. Although words can change their meaning over the years, I have always felt considerable distaste over the use of the verb 'to break' in dog training; it suggests training by overt bullying. In Youatt's 'The Dog' of 1854, he wrote: "The cruelties that are perpetuated on puppies during the course of the education or breaking-in, are sometimes infamous."

I was therefore pleased to see, in the preface to the 1908 edition of Hutchinson's book, these words by his son: "It is far less common than it used to be to see a dog brutally ill-treated, and I venture to think that the principles inculcated by my father in these pages have gone far to create a more intelligent sympathy between man and dog." The harm of course had already been done, with whole generations of sportsmen and indeed ordinary dog-owners believing that the expression 'dog-breaking' meant exactly that: breaking the dog's spirit. Yet in areas of dog use where the dog is expected to excel the dog's spirit is rightly considered to be of huge importance. Bloodhounds have to persevere; guard-dogs have to be protective; retrievers and spaniels have to like water; terriers have to like digging!

We may have stopped using the expression 'dog-breaking' but in the hunting field we still use expressions like 'whipper-in'. I realise fully what this means and know exactly how it came to be used, but it does convey an unfortunate image for the uninitiated. It is not good sense in the times we live in for any hunt servant to carry a title, whatever its origin, which conjures up visions of hounds being lashed, however unwarranted. Most hunting terms from former centuries are now obsolete and this one should join them. Words are meant to convey images, nearly always the one desired by the speaker or writer. Nowadays no sane sportsman would wish to be described as 'a good man to pig'! But in India, in the 19th century it was widely employed in the boar-hunting world. A 'skirter' in the hunting field meant a hound that liked to operate on the fringes of the pack, not the wearer of a certain form of dress!

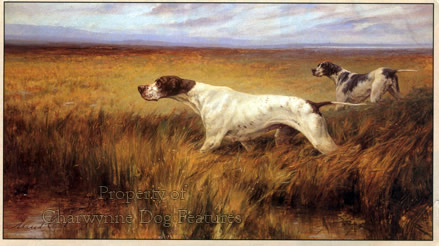

The idea that hounds of the pack need a good whipping is thankfully without foundation. Even opponents of hunting with dogs agree that hounds love their hunting, need no coercion and are arguably the fittest healthiest dogs in the land. How muted however was the outcry when one police force thought the most appropriate way to 'break' their German Shepherds was to suspend them over fences on choke-chains. Not much 'dog-whispering' went on in the Essex force in those days! Some years ago a handler at a field trial for Pointers was seen to suspend his dog off the ground by its choke-chain, so angered was he by his dog's performance. Whoever trained the dog needed suspension, not the inadequately trained animal. The pointing instinct is a strongly-inherited one - it just needs capturing.

The inherited instincts of sporting dogs has long been noted. In Cassell's Popular Natural History of 1890 it quotes: “Mr TA Knight, in a paper addressed, some years ago, to the Royal Society, remarks: “…A young spaniel, brought up with the terriers, showed no marks of emotion at the scent of polecat, but it pursued a woodcock, the first time it saw one, with clamour and exultation; and a young pointer, whom I am certain had never seen a partridge, stood trembling with anxiety, its eyes fixed, and its muscles rigid, when conducted into the midst of a covey of these birds. Yet each of these dogs is merely a variety of the same species, and to that species none of these habits are given by nature. The peculiarities of character can, therefore, be traced to no other source than the acquired habits of the parents, which are inherited by the offspring, and become what I call instinctive hereditary propensities.” Such 'instinctive hereditary propensities' also 'instruct' young terriers, sheepdogs and hounds.

An old sporting dog expression not always understood by the general public, and referred to above, is that of 'entering' a hound or terrier. It means the introduction of the dog to its future prey, for example a live rat. This introduction is vital in the successful working future of the dogs concerned. A young puppy badly bitten by a big rat doesn't forget quickly. Frankly any so-called sportsman who tells you that his four-month old terrier pup is a great rat killer, doesn't know his calling. All the old terrier-men I encountered in my youth would advise firmly against entering a pup too young. No doubt some young pups have been entered young and turned out exceedingly well. The truth is that you never get to hear of the pups put off for life by a bad first experience. Many years ago a breeder of working terriers told me his experience with a 'sportsman' he had sold a young promising dog to. The man had returned the young dog to its breeder 'because it wasn't hard enough'. He then described how he had put his new purchase in a barrel with a tom cat and it made no attempt to kill the cat or even fight it. The breeder patiently explained that the young dog had been brought up with cats, as part of its socialization, and that he never wanted any dog bred by him either to chase cats or harm them. He took the young terrier back from its disappointed purchaser. A year later this young dog killed a mink single-handed, saving the stock of a wildfowl rescue centre.

I suspect that there is an unspoken rule amongst real terrier-men that anyone seeking a really 'hard' terrier is not one of them. There is not only a wholly desirable gap between a brave dog and a canine psychopath, but a compassionate desire to avoid any precious terrier receiving needless injury. The wish not to push an inexperienced immature terrier into its combat arena too soon has parallels in the absolutely crucial need for very young dogs to be comprehensively socialized. It is as important to prepare a pup for the outside world as it is to prepare it for its specialized role. In a frightening world a tender pup needs help. Every dog needs to be 'entered' adequately as a learning pup if it is to develop into the well-balanced adult most owners desire. Successful 'entering' is the teaching of life skills to a working terrier. 'Breaking' a dog to the gun is a similar exercise for gundogs. But for most dog owners it means ensuring that their dog can cope with life's pressures and the limitations humans place on dogs in each environment they live in. To the urban dog, noise alone has to be a constant invasion of its world. For the rural pet dog, the challenges are mainly temptations, but the dog still has to cope with the frustrations. Life skills for dogs are so important if the dog is to live in harmony with its owners, neighbours and fellow dogs. Such education may be very different from the training given to young humans, but there is some truth in the modified adage: give me the pup when it's two months old - and I'll give you the dog!