860 THE BRITISH WORKING SHEEPDOG

Document_title

by David Hancock

THE BRITISH WORKING SHEEPDOG

THE BRITISH WORKING SHEEPDOG

“Let us now turn to the shepherd’s dog of our own island and the adjacent parts of the continent, which offers several varieties, more or less differing from each other. One breed from the north is covered with a deep woolly coat, capable of felting; the colour is generally grey; another breed, that generally depicted, is covered with long flowing hair, and the tail is full and bushy; the colour is in general black, with tanned limbs and muzzle, varied occasionally by white on the breast. In both the muzzle is acute, and the ears erect, or nearly so. There is a third and larger breed, called the drover’s dog…”

From The History of the Dog by WCL Martin, 1845

The British Working Sheepdog

The late arrival of the Border Collie onto the show scene has led to some ‘beautification’, but their use is ever more widespread, from the pastures to the hearth, to the agility, obedience, fly-ball and disabled-assistance support dog roles – all with great success, perhaps the most versatile breed in history. These are difficult days for farmers and farm dogs. The glamorous Rough Collie may grace film-sets and the likeable Bobtail may star in paint advertisements but neither breed works any more. The world famous and unsurpassable Border Collie now features in the show ring, but only after considerable opposition from the International Sheep Dog Society, which rightly feared a loss of functional ability and working physique. These dogs may have moved from the pastures to city streets but really they are only spiritually happy when working and quite a few are too hyper-active to make good house pets. (I had one that when alert carried his tail high and was the toughest dog I ever had, active till 17 years old. When I wrote of this in Dogs Monthly, a reader Christine Foord wrote in to say her collies had this feature too and were clever and assertive. Such a feature, if demonstrated on an exhibit in the show ring, however good the dog, would lead to the dog being unplaced.)

The challenge for their fanciers is to breed them for their new role, without losing their essential characteristics, for that is how all breeds survive. The fairly recent arrival of the breed on to the benches needs to be balanced against the long-established trial scene. As pointed out in the June Newsletter of the International Sheep Dog Society (ISDS), 1983, when considering early pedigree registrations: “The Kennel Club Gazette in its May 1983 edition, gives some interesting statistics: it shows the registrations for Border Collies since 1978. They read as follows:- Border Collies registered in 1978 – 368; in 1979 – 843; in 1980 – 735; in 1981 – 718; in 1982 – 756. Compare these figures to the Society’s registrations which have run consistently at 6,500 approximately for each of the years in question.” Such background gives some balance to the contemporary show scene, where town-dwelling owners are unaware all too often of the roots of their breed.

Challenging Review Task

It is far from easy to review the shepherd dogs of Britain covered by the titles of Border Collie (when registered with the KC) or working sheepdog (usually registered with the ISDS, although KC-registered dogs, described as working sheepdogs do compete in agility, obedience and fly-ball contests). In the pastures you see highly efficient if not always very handsome dogs, diligently performing their centuries-old tasks. In the show ring, from the ringside, it is reassuring to view top quality dogs such as: Australian and English Ch Waveney Kozmonant, Fayken I am A Legend, and his litter-sister Fayken Indecent Proposal, judged to be Border Collie of the year, and runner-up respectively, in 2013. But, in the same year, it’s alarming to read one judge’s report that states: “I haven’t been around the show world for about four years. The Border Collies presented to me came in four different types. Slab-sided and narrow headed (athletic). Square incorrect height to length ratio, incorrect forehand, i.e. forward placed shoulder, steep upper arm and square croup, short-coupled (majority). Dwarf small usually profuse coat (glamorous). A finer version of an Australian Shepherd especially in the head and stifle area. This made my judging to The Standard very difficult…This dip in quality happens in dog breeding where the generation of ‘greats’ is weakened in the next generation. This is not a slur on breeders, etc. It is what is available in the gene pool, how it is used, and if there are no lines with ‘nicks’ in them, then mediocre rules until such matings are found.” Clearly now is the time for inspired selection of breeding stock, strict observance of the Breed Standard and the pursuit of soundness so often demonstrated in the trials dogs.

The Trials Dogs

Competitions between dogs and their owners have long been a feature of rural life. They have been accused of developing dogs principally for the trials, spaniels too ‘hot’ for your average shooter to handle and retrievers too light-boned for sustained work in the sporting field and ‘flashier’ sheepdogs to satisfy their appeal for the judges. But a desire to compete was behind the first sheepdog trial, run between ten dogs at Bala in North Wales, in 1873. But, as Eric Halsall has pointed out in his Sheepdogs – My Faithful Friends of 1980: “A trial is simply planned to assess ability and is obviously of great practical value in determining the qualities of the dogs taking part. Good dogs can, and do, delight in their prowess; the human braggards – whose dogs perform wonderful feats on the hill! – have their teeth drawn; and the watchers choose their potential breeding stock. Wherever sheep are farmed, trials are held and in today’s competition when entries reach towards a hundred, even at the remotest trials, it is a very good collie that wins.” It is good to know that there are now field trials for show collies, whether Border or Beardie. Herding sheep makes unique demands on a dog; their role depends on control.

The ‘Strong-eyed’ Sheepdog

In this role, a certain type of dog is needed. The dog's instinctive defence of territory is harnessed to guard a pasture. The dogs then, without human direction, place themselves between an approaching predator and the stock in their remote pasture. This is in stark contrast with the herding breeds, hyper-active dogs which stalk, chase, bully, bark at and even bite sheep to impose their will on them. These are the 'header-stalkers', using classic canine predatory behaviour, inherited from wild ancestors. They usually feature the prick ears and long muzzles of those wild ancestors, although drop-eared dogs like the Pointers and Setters of the shooting field also make use of this instinctive ‘restrained’ focus. These dogs have to be controlled by human voice or whistle. Just as the Beardie combined the skills of driving and herding, the shorter coated working sheepdog, usually described as a 'collie', using the 'header-stalker' technique rather than that of the flock guardian, not only matched them but suited the changing ways of farming. As the railways did away with the need for drovers and the acreage of common grazing land decreased, there was a need for dogs able to move stock from one fenced pasture to another, to pen them for shearing and health checks and get them on to vehicles for market. It is likely that these shorter coated farm collies were not widely used in Wales and southern England until the livestock industry adapted to new transport opportunities. The Border Collie or working sheepdog of sheepdog trial fame is the best known 'strong-eyed' breed in the world, so-called because it exerts control over sheep by assertive eye contact and aggressive body positioning.

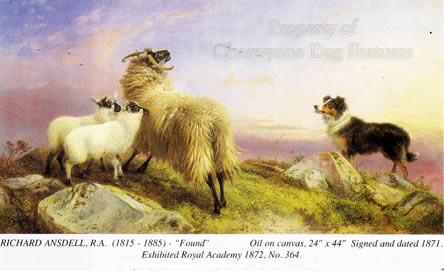

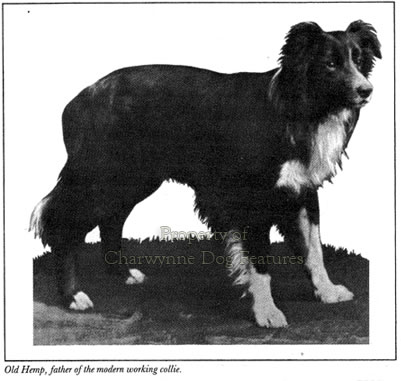

In his The Farmer’s Dog of 1975, John Holmes has written: “To revert to the question of ‘eye’, this is a subject which is often misunderstood. First of all ‘strong eye’ is not essential in the working dog and I have known many excellent ‘loose-eyed’ dogs. It can be, and often is, a liability rather than an asset…It is, in fact, a comparatively recent innovation, having been developed to its present-day strength only since sheepdog trials started, and then solely in the type of sheepdog which proved most successful at the trials.” But in his Sheepdogs at Work of 1979, Tony Iley writes: “In approximately 1790 the presence of ‘eye’ was recorded by James Hogg, the Ettrick shepherd-poet. He refers to it in a matter of fact way without surprise, leading us to believe that it was not a new innovation…James Scott of Overhall, Hawick (International Champion 1908 and 1909), said that he had not seen ‘eye’ in dogs until 1875, when he saw it in a bitch owned by John Crozier, a herd at Teviot Water, who got her from Northumberland. Because of this it can be concluded that ‘eye’ developed in various isolated families of dogs in the period between 1740 and 1870. At this time it would not be widespread, and its value would not be fully realized until the early trials began, starting with the first trial at Bala in Merioneth, Wales, in 1873.” In 1894, the supremely capable Old Hemp, reputed to have ‘eyes that blazed’, became the father of today’s working collie. He died in 1901 but not before siring over 200 top-class offspring.

The ability of a dog to identify individual animals is illustrated by an anecdote in the Rev. Charles Williams's 'Dogs and Their Ways' of 1863: "Lord Truro told Lord Brougham of a drover's dog, whose sagacious conduct he observed when he happened on one occasion to meet a drove. The man had brought seventeen out of twenty oxen from a field, leaving the remaining three there mixed with another herd. He then said to the dog, 'Go, fetch them,' and he went and singled out those very three." Different terrain and difficult sheep-rearing country led to different instincts being instilled in the sheepdogs. In their stunningly illustrated Hill Shepherd – A Photographic Essay of 1989, John and Eliza Forder write: “’Cur’ or ‘barking’ dogs have been used in the Lake District for generations and are bred especially for the job of shifting sheep in difficult terrain. They are trained to bring sheep away from crags, cliffs and undergrowth, while a sheepdog from lower, ‘cleaner’ country may resort to sinking its teeth into them through sheer frustration. Herdwick sheep, local to Lakeland, will outwit shepherds and dogs if they can.” Waist-high bracken, unfenced pastures and cruelly-concealed crags challenge both dog and shepherd; they simply have to work as a team, in this timeless rural scene.

The Revival of the Welsh Sheepdog

For over a decade the Welsh Sheepdog Society, formed in 1998, has been working to revive a distinct variety of collie based on their traditional form in Wales. They run a register of purebred stock dogs and hold demonstrations. Bigger than Border Collies and often blue merle (in the Plynlimon and Devil’s Bridge area), tri-coloured (black and tan in Tywyn), red-tan (down the Cardigan coast) and white, or a lighter sable and white, Welsh Sheepdogs are ‘loose-eyed’ herders but valued for their stamina and robustness. With powerful shoulder-muscles, folded ears, broad-muzzled faces and big strong feet, they excel in driving the bigger flocks and have a characteristic high tail carriage when working. The initial trawl for suitable breeding stock produced around 200 likely dogs, with 80 selected as foundation stock; over 1,000 are now registered with the society. They were famed as drovers’dogs, able to get large herds to market; in North Wales a big grey variety was favoured. Bob-tailed dogs are found in SE Wales, but they cannot be registered with the society. In pursuit of a bigger gene-pool enquiries have been made in Patagonia, where Welsh settlers developed the Barboucho from the dogs they took with them. The enterprise of these enthusiasts is heart-warming; the world of the pastoral dog needs such enlightened energy to ensure that old working dog breeds are respected once again.

A wholly new breed is being developed in Wales, called the Welsh Mountain Dog, resembling the old Galway Sheepdog and from a combination of breeds to suit a purpose. This handsome breed, created by Welsh breeder Lyn Kinsey, is a blend of the Bernese Mountain Dog, the Border Collie and the Loughlander, the latter created in Durham by Sue Curle-Lane by blending the blood of the Bernese Mountain Dog with that of the Newfoundland. The new Welsh breed is not as prone to the ailments that afflict many large breeds, has a sunny disposition and sound temperament, very much resembling a big strongly-built Border Collie, an admirable companion in rural areas. The pastoral breeds of Britain may come and go but they form an important part of the worldwide scene both in variety and, especially, in quality.