856 PASTORAL DOGS - THE SETTLERS' NEEDS

PASTORAL DOGS - THE SETTLERS' NEEDS

by David Hancock

Colonial Needs

Colonial Needs

Settlers need food! Those arriving in the fast-developing colonies needed sheep and cattle. A different type of stock dog was required by settlers in the wide-open spaces of America and Australia. Despite taking their herding dogs from Britain with them, the early colonists found a need to adapt them to local conditions. In Australia this produced the Barb or black Kelpie, the Kelpie and the Australian Cattle Dog. The striking resemblance to old forms of our native breeds in these emergent breeds is undeniable. I have seen working collies in Britain that could pass at first glance as one of the Australian breed. The Australian Shepherd, owes more to the United States for its development, but is very similar to the bob-tailed sheepdogs of the Black Mountain, on the Hereford border with Wales. In New Zealand, the Huntaway was produced, a barker rather than a silent worker like our collie but still reminiscent of our old black and tan sheepdog.

Antipodean Herders

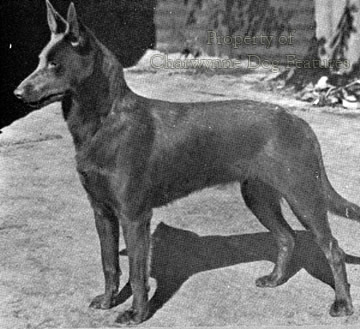

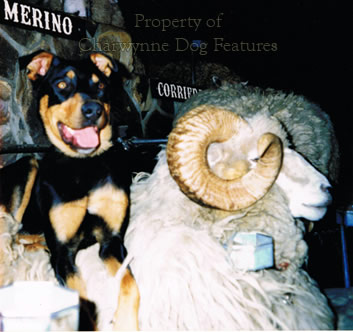

Anyone who has read Robert Hughes's The Fatal Shore (Pan Books, 1988) will retain a lifelong admiration for those who went to Australia in its earliest years of development by Europeans. This admiration must be extended too to the dogs that accompanied the earliest settlers. Certainly, on the long arduous journey out there, dogs would have suffered as much as any human, if not more. It is worth remembering that when considering the surviving breeds of Australian, and indeed New Zealand, dogs. It is hardly surprising that breeds like the Australian Cattle Dog, the Kelpie and the Huntaway of New Zealand are among the toughest of breeds of dog in the world. Writing in the South African Merino Breeders Journal in 1941, Mr W Ross wrote an article entitled: “Training a Sheepdog” in which he stated: “As far as we are concerned, there are only the Border Collie and the Kelpie to choose from…the Kelpie is an Australian breed. It varies a lot in colour and size and probably springs from the same source as the Border Collie, with possibly some admixture of blood far back. That does not, however, detract from its present value. You will probably find the Border Collie is more obedient and stylish while the Kelpie is hardier.” This hardiness is an immense benefit in an unforgiving sheep rearing country such as Australia; sheep farmers are not looking for pets - in any country.

It is hardly likely that ornamental dogs would have accompanied the early transport ships to Australia and New Zealand; it is certain that dogs valuable enough to have merited passage in this way would be workers: herding dogs, hounds or terriers. Dogs in these three latter categories would have gone on this long hazardous voyage because they would bring benefits at the far end to their owners. It is not good sense however to link them with contemporary breeds because breeds were not valued in the 18th and early 19th centuries; function ruled. It is of value however to link them with the common dogs of England at that time.

Sheep and cattle being taken to the Antipodes would have been accompanied by herding dogs. Terriers and hounds would have been valued as vermin-controllers and pot-fillers. Big strapping mastiff-type dogs would have been valued as guard-dogs and seizing-dogs. Later on, sportsmen would take gundogs and packhounds. This, I believe, is the background for considering the development of breeds from down-under. The Australian Cattle Dog is often stated to have come from a mixture of smooth merle collies, dingo, Dalmatian and black and tan Kelpie. The dingo blood is stated in one Australian publication to have introduced silent working, the red coat colour and the heeling instinct. The latter being covered by these words: "A dingo trait is to silently creep up behind an animal and bite, and these cross pups followed this style of heeling."

A reasonable response to this, to me, incredible statement would be: British working sheepdogs work silently; red merle is in the collie gene pool - it doesn't need an infusion of dingo blood; and the heeling instinct was present in British herding dogs before any Europeans reached Australia, ask any Welsh Corgi or Lancashire Heeler breed historian. As for the infusion of Dalmatian blood, can you truly imagine any hard-bitten weather-beaten cattle farmer introducing the blood of a spotted coach-dog to, as the Australian publication puts it: "give the progeny a love of horses and a sense of responsibility for guarding their master's possessions." My working sheepdogs loved horses and were naturally protective of me, my family and our 'possessions'. Why did no English farmer find it necessary to infuse his working pastoral dogs with Dalmatian blood?

Noreen Clark, in her 2003 book, A Dog Called Blue, The Australian Cattle Dog and the Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog 1840-2000, an excellent piece of research on these breeds provides authoritative background to this subject. Her researches show that the Dalmatian theory was invented by an Australian dog ‘expert’ called Kaleski, with no evidence whatsoever, perhaps an uninformed hunch to account for the blue ticking in the breed’s coat. But genetic research alone has shown that a quite different gene is responsible for this and not present in Dalmatians. Despite this incontrovertible contradiction of Kaleski’s theory, we have the KC, in their official Illustrated Breed Standards, published at regular intervals, as updates, by Ebury Press, stating: “Behind the Australian Cattle Dog are breeds such as the Dingo, the Kelpie, the Dalmatian and the Bull Terrier, but the breed has been purebred since the mid-1890s.” Apart from the fact that the dingo is not a breed, it is not impressive for a publication that really should be authoritative to be so totally wrong.

The Australian Cattle Dog is respected in many countries for its mental toughness, physical robustness and serious approach to work. In his 'Hunting Big Game with Dogs in Africa', the American Er M Shelley, gave an admiring pen picture of one of these dogs. He described her as: "...a wonderful hunting dog. She could trail nearly as well as a hound, and, when it came to fighting in dense places, I have never seen a dog that could compare with her. She possessed the power and had the courage to force a lion from place to place in dense cover, while large packs of dogs could not move him at all. In after years she was used by Mr Rainey to bring both lions and leopards out of dense reed beds, where his entire pack of forty or fifty hounds and Airedales could not move them."

That is some tribute from a man with immense experience in hunting big game. I have pointed out that unsubstantiated theories that the Australian Cattle Dog came from root stock of two Scottish blue merle working collies crossed with dingo, with Dalmatian (see above) and Kelpie blood introduced later. I see Bull Terrier features in the anatomies of many ACDs but am told that the outcross to the Bull Terrier was not considered a success and not favoured. The dingo blood is alleged to have produced the inclination to creep up behind cattle and bite them. But there has never been a shortage of British working collies with the instinct to get behind stock and nip it into compliance. I once owned two working sheepdogs that would nip the hocks of cattle as a herding tactic without any training to do so.

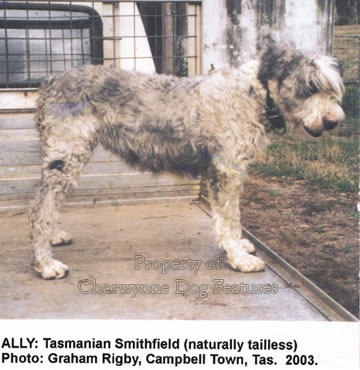

I suspect that the blue-mottled or speckled coat of this quite admirable Australian breed has given rise to such weird conclusions, was certainly behind Kaleski’s invention, mentioned earlier. As mentioned in an earlier section, it is not unusual too to find the Australian Shepherd linked with Basque shepherds emigrating to Australia in the 19th century. But this attractive breed displays the range of coat colours found in our working sheepdog gene pool, as is the naturally bobbed tail. Why on earth would colonist-farmers, living in a tough climate in a new land, rush to use Spanish dogs when their own were so proficient, it makes no sense at all. An Australian fancier of the Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog told me a comparable calumny, that this breed developed from the Smithfield Sheepdog, brought out from England, hence the bob tail.

Firstly, the Smithfield Sheepdog was like a leggy Old English Sheepdog, usually sporting a full tail; secondly the naturally bobbed tail occurs in working sheepdogs, as those on farms on the Black Mountain on the Welsh/Herefordshire border indicate to this day. To claim a false provenance for any modern breed degrades that breed; to restate a false origin demeans the fanciers of that breed; to record for posterity a false compilation for a breed in defiance of historical facts is simply deceitful. I could believe however that the so-called Tasmanian Smithfields could be descended from our Smithfield dog; it is sizable, shaggy and a very competent all-round sheepdog. Perhaps the Tasmanian dog could be used to improve some of the sad examples of the Old English Sheepdog being proudly shown in Britain.

One Australian breed to do well here is the Cattle Dog, already supported by a devoted collection of fanciers, with as many being registered annually as our own Smooth Collie. When I told my Australian colleagues some twenty years ago that a British breeder had imported a pregnant ACD bitch, the response was 'Oh no! These dogs are not pets!' And I could understand such a reaction. But this bitch was imported by John and Mary Holmes, who had a greater knowledge of dogs, especially working dogs, than most. Sadly deafness appeared in the litter born to this bitch, a red speckle from the Landmaster Kennels in Adelaide. But this problem was tackled by breeders here and in its native country; honesty and openness always helps to reduce inheritable defects in any breed.

I have been able to benefit from studying a CD Rom, kindly sent to me by ACD-expert Noreen Clark, referred to earlier, that portrays specimens of the breed, whelped before 1950 and going right back to Hall's Heelers of around 1890. Each of the dogs depicted could have been described as a working sheepdog from here. There was no detectable sign, in dogs spanning sixty years of the breed's development, of dingo, Bull Terrier or Dalmatian influence. Most of these dogs were leggier than the contemporary breed. I do hope the requirement for the breed to be slightly longer from the point of shoulder to the buttocks than the dog's height at the withers isn't being overdone. This is a working breed par excellence and one deservedly admired by all who come into contact with it.

The Australian Shepherd, perhaps better named the American Shepherd - for that is where it was promoted and developed, is very much an active, alert, eager to work breed. It has an attractive and remarkably wide range of coat colours, but no more so than our own native equivalent. It has a naturally bobbed tail, just as some of our native working sheepdogs do. It is becoming popular here, with 87 registered in 2001 against not one ten years ago. In 2012, 124 were registered here and I saw some excellent specimens at the Bath Dog Show in 2013; two recent critiques have however issued warnings:

Australian Shepherds, Ch Show, 2011: “…after almost 20 years exhibiting and judging Aus Shepherds, it was disconcerting to see so many fine-boned exhibits often with accompanying narrow heads. The breed’s purpose is to work cattle and sheep. Too many exhibits on the day were lacking in the required muscle, while several exhibits were over-angulated at the rear; yes, they may look good when standing but they lack drive on the move.”

Australian Shepherds, Ch Show, 2012: “Front angulations were poor in many, giving the impression of stuffy necks and stilted front movement…Please remember this is a working stock dog and should be able to work all day under all conditions, so should be well made and sound.”

When I was in Northern Spain a few decades ago, returning home from a year in Gibraltar, I recalled the alleged link between this breed and Basque dogs. I was mainly researching a breed called the Euskal Artzain Txakurra or Basque Sheepdog, but I enquired about merle sheepdogs being used by Basque shepherds. No livestock breeder, archivist or dog historian there could provide substance to the claim that such dogs had gone to Australia with sheep in a previous century. In my car, I had my own working sheepdog. A Spanish farmer looked at him and said: "Remember, our dogs have never worked as your dogs do!" If that is so why would hard-pressed Australian sheep farmers, working in a harsh climate for sheep and dogs, wish to weaken the blood of their highly competent, ‘strong-eyed’ sheepdogs, even if such Basque dogs were available at all? But the Kennel Club's official history of this breed presents this claim as proven. Their evidence would be of more than passing interest! Accurate breed histories are so undervalued; when throwbacks occur or inheritable conditions rear their ugly heads, ancestry really does matter. So often when mis-marked pups crop up a misalliance is blamed when it is merely the extended dormant gene pool manifesting itself.

The Australian Kelpie is alleged to have a diverse gene pool, perhaps because it has a far wider range of coat colours, based on black and its derivatives, with strange claims of 'Russian Collie' origin and an Eve-like ancestry from one bitch called 'Kelpie'. I prefer to link them with the old fox-collies of Scotland. As Iris Combe points out in her 'Herding Dogs' of 1987, the crofters on the Western Isles in the 19th century used Kelpies (called just that) to work cattle and which were determined enough to make the cattle swim at low tide from one island to another. These dogs were described as bear-like, with similarities to Scandinavian herding dogs and a hint of Viking introduction. The Kelpie is finding increasing favour in North America – as is the Australian Shepherd, with outstanding dogs in Canada such as Chs Bayshore Stonehaven Heart Breaker, Clearfires Hang Onto Yer Hat and Clearfires Dreaming In Colour. A miniature form of the breed is being developed too, with Shadylanes Gamblin Girl at Stoverly a fine example.

New Zealand's Dog

These dogs of Australia are matched in toughness by the Huntaway of New Zealand, a 'bark-collie' for want of a better description. Strongly-made black or black and tan dogs, they have been accredited with Labrador blood, but if you were a sheep farmer would you introduce retriever blood? The habit of Victorian dog writers, who on seeing a breed for the first time, immediately linked it with a local look-alike, has been echoed by some contemporary writers but is seriously flawed. There are any number of black and tan smooth-haired pastoral dog breeds, ranging from the Beauceron of France to the Entlebucher and Appenzeller of Switzerland. If you were seeking the creation of a pastoral dog why use non-pastoral dog blood, when you can capitalize on inherent talent waiting to be drawn out? What herding qualities does non-pastoral dog blood bring?

For the Huntaway Championship, each dog is required to work three sheep up a slope for about a quarter of a mile passing through three sets of flags. Each set is 22 yards apart and arranged in a zigzag course, the dog having to bark before going through the second set of flags, or be disqualified. Twelve minutes is the time allotted for this course. For the dog, accurate movement and utter concentration is essential. The trial Huntaway has to demonstrate that it can handle three sheep; the dog is expected to be forthright in method without panicking the sheep. When sheep are jammed by sheer numbers, the Huntaway will 'mount' the flock, or run over the backs of the sheep, just as the old English sheepdogs of Sussex once did. Brian Davies, a sheep farmer in Sennybridge, now uses this breed, having seen them working in New Zealand. He finds they make the sheep less nervous; the Huntaway's barking seeming less of a menace than the silent stalking threat of a collie. Bark-power can be more useful than eye-power in some herding situations. These Antipodean herding dogs were developed in testing conditions; their ancestors survived the voyage and the demands of opening up a new country. Prize them!

Further Afield

In his Dogs and Their Ways of 1863, Charles Williams wrote on the cattle dogs of the Hottentots of South Africa, stating: “When the Hottentot takes his turn to go with the herds to pasture, he is accompanied by his dog or dogs. None have more skill in watching and driving the cattle than these have. While the herds are on their way, they are incessant in their attentions to the flank and rear, barking sagaciously to keep them in the proper line. On arriving at the place where the cattle are to graze for that day, the dogs employ themselves, without bidding, partly to fetch in stragglers and keep the cattle together, and partly in scouring the fields in the neighbourhood of the herds, which they do from time to time when required, in a body, to keep off the wild beasts.” Those words could have been applied to many different tribes and countries over many centuries; such is the international need and value of the pastoral dog to man. Farmers in Namibia have benefited from the 300+ Kangal Dogs sent there by the Cheetah Conservation Fund and now extended to Kenya, to protect cattle and cheetahs by deterring them from grazing herds, without their lives being threatened.

The Atlas Sheepdog of Morocco, also known as the Aidi or Kabyle Dog, is claimed to be a rarity, a pastoral breed of non-European origin. The Kabyles were the aborigines of Barbary and kept sheep, cattle, goats, camels and donkeys. Employed as a drover but with a nasty reputation as a guard dog, they are prized for their versatility and selectively bred for their alertness and aggression. The Algerian Sheepdog may simply be a French dog imported by settlers; it certainly has a definite Berger de Beauce look about it. Another ancient breed, the Canaan dog of Israel, was restored literally from the wild by Dr Menzel in the late thirties. She found amongst the feral dogs of what was then Palestine, a distinct 'collie' strain, believed to be abandoned herding dogs of the Bedouin. Once restored by a careful breeding programme, they excelled as guide dogs for the blind, sentry and messenger dogs and in sheepdog trials; 400 of them were trained for mine detection work in World War II. Strangely, the Canaan Dog has a definite 'spitz' look to it, featuring the bushy curled tail and prick ears of the northern dogs.

It would a worthy action if some enthusiast were to attempt the re-creation of the Old Welsh Grey sheepdog using the blood of the Patagonian Sheepdog or Barboucho. This dog is believed to have descended from the old Welsh breed after Welsh settlers took their dogs with them to the Chubut valley at the turn of the century. Known for centuries in Sardinia is the Fonni Sheepdog, a strongly-made goat-haired sheepdog, looking a little like both a Picardy Sheepdog and a Labrit, and perhaps related to it. The beardie type is famous for its cleverness and quick response to training; the French army making good use of both Briard and the Labrit as a messenger in the Great War.

In India, the Dhangari Sheepdogs of Maharashtra have a distinct Border Collie look about them. They are used for herding in the Western Ghats, where huge flocks of goats and sheep are grazed. They move with the caravan, acting as sentries at night, but also hunting for small local game. Twenty inches high, around 25 pounds in weight, they are usually black with white on the brisket, under-belly and legs. With a reputation for being

the best dogs in rough or mountainous terrain, extremely hardy and breeding true to type, they may now be lost to us as, when on the move with their nomadic owners, they breed with local dogs and lose identity. The Vikhan is a big flock protector in the Chitral region of NW Pakistan, often wearing the classic spiked iron collar to protect the throat, their wool being spun to produce fabric for winter clothing. The Bhutia and the Bisben in the Himalayas may also have been lost; related to the Tibetan dogs, they are big substantial herder-flock guardians with long, shaggy hair in winter but shed in summer. Renowned for their fierceness towards strangers, they are remarkably robust, famed for their hardiness in extreme weather conditions. The famous Mastiff breeder, WK Taunton, exhibited an ‘Afghan Sheepdog’ called Khelat in 1920 that may have belonged either to this breed or an allied one, such as the Bangara Mastiff.

Settlers’ Dogs

In the United States a survey in the 1940s revealed that their most numerous breed was the humble farm collie, still looking much like its British ancestor. One American Kennel Club recognises these dogs as a formal breed, known as the English Shepherd. They also have a breed they call the McNab dog, a smooth collie descended from sheepdogs taken to California in 1885. But inevitably the Americans found a need to meet their own cattle-dog needs and a breed now known as the Catahoula Leopard Dog created. Catahoulas are essentially gathering dogs, having a natural tendency to circle to the other side of stock, opposite the handler. They specialise in gathering rough wild cattle and even hogs. They track the stock, bring it to bay rather like a hound, bark loudly to attract the stockmen and often work in teams. They remind me of the Portuguese Cattle Dog, Cao de Castro Laboreiro, which has a comparable function as a herd protector and drover. Catahoulas are unlikely, in their unique marbled-harlequin or black merle coats, to be  confused with another breed.

confused with another breed.

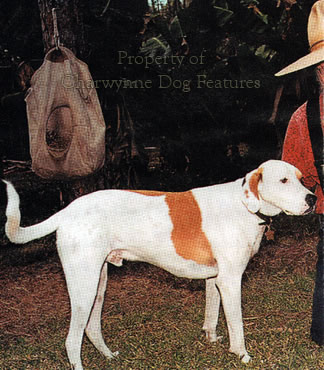

Created Breeds

American dog-breeders are not slow to develop their own variant of another nation’s breed, as the American Cocker Spaniel, the American Bulldog, the American Staffordshire Terrier and the American Water Spaniel demonstrate. They sometimes refashion a breed name – as with their so-called English Shepherd and the Amstaff but don’t shy away from renaming a refashioned variety – as their King and Shiloh Shepherds indicate. They also recognize the merits of an all-white GSD. In producing their own shepherd dog, the Shiloh Shepherd, they claim it is more like the old-style GSD, heavier-boned, more heavily-coated and more muscular than the modern German dog. It could be that in such a way old farm breeds are restored to their original type. The American and Australian pastoral breeds are often more robust than some of ours. The English Shepherd is very similar to the so-called Australian Shepherd, also developed in the USA, and often naturally ‘bobbed’ and ‘loose-eyed’ too. (American dog breeders have produced a miniature version of both, but as companion dogs.) Registered as a breed with the United Kennel Club (UKC) but not the American KC, their equivalent of ours, they are mainly farm dogs, usually tri-coloured or black and tan and have a sound reputation as workers. In a highly individual coat, comes their Blue Lacy, mostly slate-blue, sometimes with tan, and with a formidable reputation as cattle dogs of great resolve. They all but died out until enthusiast HC Wilkes in 1975 ensured their survival with a revitalized breeding programme. Brought ‘out west’ by the Lacy brothers around 1848, and about 45lbs in weight, when solid gun-metal grey, there is a distinct ‘reduced Weimaraner’ look to them. Like the Catahoula Leopard Dog, they are unlikely ever to be confused with another breed, truly all-American. In Florida they have developed their own drover’s dog, the Florida Cow Dog, a strongly-built, often lemon and white, smooth-haired dog, worked in teams and alleged to be able to keep a herd together throughout an overnight stop.

The American Cattle-Pinning Dog

In modern America, a breed called the American Bulldog, but more like a Bullmastiff than a Bulldog, and now well-known here, is still used to drive wayward cattle and to catch hogs, a very dangerous activity and one in which the dog can be killed. These powerful, resolute dogs hurl themselves at the hog, which weighs three times their weight, and seize it by the ear, hanging on despite every effort of the enraged hog to shake them off or harm them. The sheer almost reckless bravery of such dogs is quite remarkable. Not classic pastoral dogs but livestock-penning dogs, they match the role of the Cane Corso in Italy, the Rottweiler in Germany and the Bardino and Perro de Presa Mallorquin in the Mediterranean. When judging American Bulldogs, I have striven to emphasize the importance of agility, speed and balance in a breed destined for such a role. But their fanciers have been obsessed with size in their dogs – both in weight and height at the withers, almost prizing sheer bulk at the expense of functional capability. When judging Victorian Bulldogs, dogs reshaped like their distant ancestors rather than designed to win in the show ring, where the short muzzle and enormous head is strangely desired, I try hard to choose the more athletic exhibits. Real Bulldogs were either athletic - or dead!

Cattle or Butchers’ Dogs

In the Mediterranean islands the Cao de Bou (Cowdog) and the Fila de Sao Miguel are used as cattle-drivers. The Sicilians developed a cattle dog, called the Branchiero, that worked in a unique way, leaping at the head of the herd leader to turn it in the required direction. It resembled the Rottweiler, another one-time cattle dog and also alternatively called 'Butcher's Dog'. Stockmen and butchers have long had a need for powerful dogs that could 'hold', 'pin' or grip wayward cattle, difficult rams or highly determined boars, especially in places where the herd ran semi-wild. Predictably they opted to employ 'catch' or 'capture' dogs from the hunting field. These dogs developed from the hunting mastiffs used by primitive hunters to pull down aurochs, buffalo and wild bulls before the invention of firearms. These holding dogs were used quite extensively as the emergent types subsequently demonstrated: the Bullenbeisser in Germany, the Niederlandischer Bollbeisser of the Netherlands, the Cao de Bou in Mallorca, (their breed titles alone revealing their function), the Fila (literally 'seizing' or 'pinning' dog) Brasileiro of Brazil, the Perro de Presa (literally 'gripping' dog) Canario from the Canaries. Such dogs needed power with speed, agility with skilful timing and great resolve backed by instinctive judgement; they did not need massive bulk and great size – impressive in the show ring, disastrous in the stockyard!

In his Dogs and Their Ways of 1863, Charles Williams recorded: “On the arrival of vessels with livestock in our West Indian colonies, the drover or cattle-dog of Cuba and Terra Firma is often of great service. The oxen are hoisted out by a sling passed round the base of the horns…and allowed to fall into the water…one or two dogs catch the bewildered animal by the ears, one on each side, force it to swim in the direction of the landing-place, and instantly let go their hold when they feel it touches the ground; for then the ox naturally walks up to the shore.” In this act by determined dogs, there is a combination of astonishing resolve, immense natural skill and instinctive tactics when faced with a giant ox that is terrified and panicking, deserving of great admiration. Settlers wherever they landed needed pastoral dogs to survive and they owe their dogs a great deal - they were sometimes the difference between surviving or starving!