848 RECASTING THE PEDIGREE SYSTEM

RECASTING THE PEDIGREE SYSTEM

by David Hancock

Recasting the Pedigree Recording System

Recasting the Pedigree Recording System

The last few years have been momentous in the world of the domestic dog. The canine genome has been unravelled, the dog's DNA analysed, health clearances are increasingly available and quarantine relaxed. But if you study the records of just over a century ago, the French expression, 'deja vu', comes to mind; there is that illusory feeling of having already experienced a contemporary happening. A glance at the dog scene of 1883 provides all the material to explain that nostalgic sensation. In a letter to the Kennel Gazette of that year, a Gordon Setter breeder boasts that his bitch 'had eleven whelps on the 2nd of January 1883, eleven more on the 18th of July following, and that she is in whelp again, and due to pup January 25th (1884)'. Over-breeding is no new phenomenon. In the same issue of the Kennel Gazette, the Old English Mastiff Club adopted 'The Points of the Mastiff', which required a massive body, a short muzzle, small eyes, heavy shoulders and very large bones in the forelegs. Such requirements still afflict this breed today.

In 1883 too, Dean and Son published a further edition of the first dog book to contain photographs of winning dogs, 'Dogs' edited by Henry Webb. Webb records that in 1861, the dog show in Holborn attracted 240 dogs in 48 classes, but in 1871 the Crystal Palace show drew 834 entries to 110 classes. The biggest increases occurred in Pointers, Setters, Mastiffs and Fox Terriers. Terriers were classed as non-sporting dogs. Keepers' Night-dogs, the Bullmastiffs of today, and Harriers were both recognised and shown. Webb wrote of Skye Terrier classes for short and long-coated varieties and drop-eared and prick-eared varieties too. The breed was then required to be 'three times as long as he is high'. It is not difficult to see where the exaggerations started, although today the breed is expected to be only twice as long as it is high. There could so easily have been a 'Norfolk/Norwich' Terrier situation in the breed over ear-carriage, but both sets are tolerated today.

Varying Nomenclature

The Field Magazine of 1883 covered dog shows very comprehensively, their editor acting as a judge at some. This sporting magazine covered the Ostend Dog Show, attended by British exhibitors, and the appearance in English field trials of Pointers and Setters from the United States. With progress, we might one day be able to achieve the latter again! It is noteworthy that Great Danes were termed German Mastiffs at one dog show, Boarhounds at another and German Boarhounds or Saufangers (literally pig-catchers) at the Essex Agricultural Show, all in the space of a few months. Nowadays Great Danes are still denied their hound ancestry and languish in the Working Group. But once again British exhibitors can now enter dogs at a show held in Ostend.

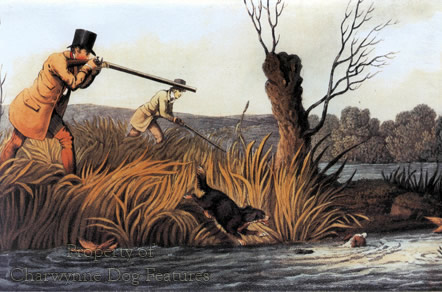

A number of breeds now lost to us featured at the 1883 shows, the English White Terrier and the English Water Spaniel among them. Rather than touring the world looking for exotic breeds to import as kudos-earning novelties, perhaps one day a patriotic breeder will attempt to re-create these lost native breeds; it would be timely and deserved. We have gained some admirable foreign breeds, it is undeniably true. But I would be better pleased to see the admirable Harrier restored to the list of recognised breeds, along with born-again English breeds like our lost Water Spaniel and White Terrier. Is every foreign breed being favoured here truly more meritorious? Do we not care about our canine heritage?

In the last 120 years many aspects of owning and breeding dogs have changed. Some sadly have not and there is often human frailty behind such failings. What is especially disappointing is the failure of the pedigree form itself not to move with the times, respond to increased knowledge and our ability to obtain and store information. If you look at a pedigree form of 2004, it could so easily be one from 1883: five generations of names of sires and dams, nothing else. Is this Kennel Club inertia, an unwillingness of breeders to expose their shortcomings, mere laziness or a fear of progress itself? There are needs not being met here, a significant omission of any indication of quality through grading and no genetic content. Both omissions do not advance the science of dog breeding or the stated desire to improve dogs. Is a healthier breed not worth pursuing?

Grading the Entry

We now have every facility for recording not just information on the phenotype of each pedigree dog, but the genotype too. But do we have the will? On mainland Europe, dogs examined at dog shows are not just placed in order of anatomical merit, they are graded too. This grading or classification relates to their assessment against the beau ideal for that breed; usually these grades are listed as Excellent, Very Good, Good, Satisfactory, Poor and Unsatisfactory. The top grade cannot be achieved until the dog is 2. A dog graded Excellent is considered to be exceptional, with no major faults, an admirable character and correct dentition. Unsatisfactory exhibits would be very poor specimens and be unlikely to be bred from---that is the major value of grading to me.

Why should we be afraid of such a scheme? Do we not accept that far too many poor quality pedigree dogs get bred from, partly because nobody is brave enough to tell their owners how poor they are? This system of judging may be slower but is speed-judging the best way to identify future breeding material? But a far more important omission on pedigree forms is any reference to the genetic health of the subject dog. In his most informative book Control of Canine Genetic Diseases (Howell Book house, 1998), George Padgett, himself a vet and professor of pathology, makes a compelling case for the inclusion of genetic information on pedigree forms. Such an inclusion could play a vital role in reducing the incidence of inherited diseases in breeds of dog. Is that not desirable?

Recording Genetic History

Padgett points out the need for a registry capable of recording genetic histories in registered dogs. He is wise enough to acknowledge that breeders cannot map their dogs alone. He writes: "You do not have to be around dog breeders (purebred or otherwise) very long before you realise that the vast majority of these breeders do not have the background to allow them to draw the most accurate conclusions about the genetic makeup of a phenotypically normal dog based on a disease occuring in one of its first-degree relatives." He sets out a distinct role for registries, like our Kennel Club. He also provides the view that: "We need to forget the registries we had yesterday, because it is obvious that they did not accomplish what we thought they would. It's time to get out of the 1960s and move into the new millennium." Time too surely to get away from the pedigrees of 1883 and enhance the value of registration itself.

Padgett cites the work of a group of American breeders, in the Northwest, who reduced the prevalence of Collie Eye by 38% over a three year period. He mentions the achievement of Portuguese Water Dog breeders there who all but eliminated the breed's storage-disease problem in just a few short years. He concludes that: "It is clearly time for breeders, breed clubs, the AKC and the veterinary profession to come to grips with the problem to preserve the integrity, health and well-being of our canine friends." Again and again he stresses the key role of the registry and the need for such a body to review its role in a new millennium. Whilst we rely on the same piece of paper to certify a dog's birth and the names of its ancestors as we did in 1883, we miss a golden opportunity to advance. Such things must never remain the same, they must change.

Do we truly want to be stuck in 1883 as far as the compilation of written pedigrees is concerned? Robert Louis Stevenson wrote a classic, Treasure Island, in 1883, but he produced a classic phrase two years later, the desire 'to change what we can; to better what we can...' This should be the leitmotiv of every dog breeder and dog-registry; perpetuating the past is just not good enough for dogs. Bettering the past is the real challenge. We have the technology to better the past, all we need is the will and the vision. This is an opportunity for our dog registry, the much-criticised Kennel Club, to delight us all. And what a mission statement that would make: To establish before 2013 the issue of a written pedigree for every dog registered with us, setting out the quality of its phenotype and the health of its genotype.

The time frame should frighten no one; the information should please anyone who cares about the welfare of dogs and the integrity of breeds; the intention should impress everyone who seeks to better the lives of domestic dogs. Livestock breeders sneer at dog breeders sometimes, calling them Luddites. Breeders themselves want to enjoy a degree of freedom in their work, but surely not the freedom to breed crippled dogs. 1883 was an interesting year in dogdom; 2015 could be too.

Protecting the Constitution

There are any number of canine terms or descriptions which over the years have either fallen into disuse or lost their meaning. Words like messet, riggot, sapling and lymer; expressions like dog-breaking, in and in breeding, saw-horse stance, sand toe and east-west action, and distinct forms of a breed like a fox collie, a Wold greyhound, an Anglesea setter and a chinchilla hound have all lapsed. There is one old-fashioned word however which could with justification be revived, the word 'constitution'. As a boy I can remember being asked by a kindly relative if my puppy had a 'good constitution.' It meant robustness, natural resilience, disease-resistance or, in old dictionaries, the natural condition of the body. Sadly, today, far too many dogs are not robust, have little natural resilience or disease-resistance and their bodies are simply not in a 'natural condition'. I have grave concerns about the constitution of our mastiff breeds; they have lost virility.

A century ago, writers prized constitution in their dogs. The Foxhound Magazine of 1909 referred to inbreeding as a threat to it: 'a great (perhaps the greatest) factor of success in the field, namely, constitution, is lost' .The writer had found from personal experience that 'loss of constitution entails many evil consequences', listing the inability of hounds to hunt when required, increase in mortality from disease, irregularity of conformation and lack of physical development. A century later, are we breeding dogs with an enhanced constitution, what with scientifically designed food, immense advances in veterinary science, thousands of books on rearing and caring and a century and a half of dog-shows exhibiting the 'best of the very best'? Dissenters might argue that modern dog food is weakening our dogs, over-immunisation is harming our dogs and modern lifestyles punishing our dogs! An elderly vet told me recently that it was his view that today's dogs were sicklier than at any time previously. Big dogs need a sound constitution so much more than lighter smaller breeds; height and bulk make greater demands on a dog's physique.

Need and Value of New Blood

A couple of decades ago when the management of a rare breeds farm was part of my responsibilities, we crossed a wild boar with a Tamworth sow to create what we called an 'iron-age pig' . The resultant piglets were astonishingly virile, amazingly robust, remarkably precocious and just glowing with health and vitality, noticeably more so than the pure Tamworths and Gloucester Old Spots. When our pure Bagot goats became unacceptably prone to bloat, we successfully out-crossed to a Swiss breed, reducing the incidence of bloat to practically zero and producing far more robust more active kids. After three generations of breeding back to pure Bagots, every trace of outside blood had disappeared and our stock once again won at the livestock shows. When I mention this to pedigree dog breeders they pretend not to hear! We can recreate our Mastiff using Great Dane, Tibetan Mastiff and Bullmastiff blood in days gone by but we cannot let the breed benefit from outside blood today!

No Foxhound breeder would endlessly breed just from his own stock. In seeking, not just a stronger constitution, but enhanced performance, outcrosses would be introduced: to French hounds, Fell hounds, Harriers, American Foxhounds, Welsh Hounds, even Bloodhounds, as well as drafts from other unrelated packs. Breeding for function imposes such a method; but in the show dog world such thinking would instantly reveal the 'only over my dead body' school of opposition. When a BBC programme on dogs mentions the dreaded word 'eugenics' the pedigree dog breeders reach for their shotguns. Perhaps they should reach for their books on genetics. In the wider livestock world, purity of blood is only valued when it's working. Our famous breeds of dog came to us from open-minded pioneer breeders using the best blood they could and to the best purpose. To permit your breed to become paralysed by its genes is not my idea of animal welfare, not sound breeding practice and certainly not the most convincing way to demonstrate affection for a breed.

Perils of Consensus

Surrendering to consensual thinking or committing your stock to 'fashion' can never improve it. Writers in the Foxhound Magazine of 1909 had no doubt about the dangers of only breeding a 'fashionable' hound: 'We maintain the real cause is the result of loss of constitution from inbreeding, in order to obtain the requirements of the one exclusive Show standard type and the artificial characteristics necessary to the same object. ' and ...the answer is that the constitution of the fashionable hound, deteriorated by the process of inbreeding...is consequently unable to take his place in the field so frequently... ' Another contributor wrote that 'In course of time the crosses of one line of blood become so numerous that, whilst type is produced (and even that will in time fail to ensue...)...constitution is lost. ' These writers bred superb hounds, for function, and their words should not be dismissed lightly. Heavy hounds such as the mastiff group need brave and loyal breeders not mere perpetuators.

I applaud the Kennel Club's campaign to breed dogs that are 'fit for function'; if they see it through then every breed, not just the sporting ones, should benefit. In quite a significant way it could be the leading edge in a new canine fundamentalism. For dog breeders this isn't merely a change of approach, it is a moral challenge. The Czech-born writer-philosopher, Milan Kundera, has a message for us all when he writes: 'Mankind's real moral test, a test so radical and so deep that it escapes our gaze, is probably the one of its relations with those that are the most at its mercy: the animals.’