842 THE RUNNING MASTIFF OF SOUTHERN AFRICA

THE RUNNING MASTIFF OF SOUTHERN AFRICA

by David Hancock

The African Dog: The Mastiff of Rhodesia

The African Dog: The Mastiff of Rhodesia

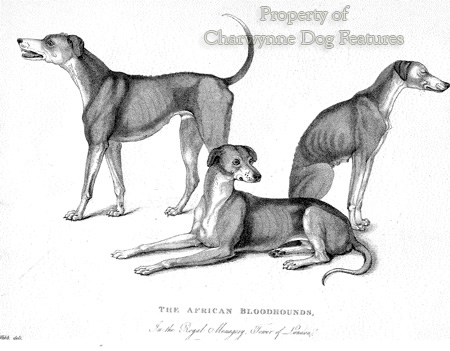

Hunting 'at force', using par force hounds which used sight and scent in the chase has long given way in Britain to 'hunting cunning', in which the slower unravelling of scent by hounds is favoured. But in Britain we did once use 'full-mouth' hounds, heavy-headed hounds with shorter muzzles, and 'fleethounds', which went too fast even for the most speedy steeplechaser. In the colonies, however, the early settlers had a need for hound-like dogs that could hunt at speed, using sight and scent. In India, for example, local breeds were utilised, like the powerful Sindh hound, the swift Rampur hound, the Poligar, the Vaghari hound, the Pashmi hound and the strongly-built Rajapalayan dog.

Ridged Native Dogs

In southern Africa, however, the settlers blended the blood of native dogs with imported breeds like the Pointer, the Bull Terrier, the Irish Wolfhound, the Foxhound and possibly Dutch breeds like the Nederlandse Steenbrak. Some of the native dogs carried a ridge of reverse hair, roughly in a fiddle shape, along their spine. The Kalahari San were seen in south-eastern Angola forty years ago with ridged hunting dogs. The Khoi were recorded as far back as 1719 as owning hounds 18" at the shoulder, with a sharp muzzle, pointed ears, with a body like a jackal and a ridge or mane of hair turned forward on the spine and neck.

Hunters' Needs

Renowned South African hunters such as Petrous Jacobs, Fred Selous and Cornelius van Rooyen, who bought his first 'lion dogs' from the Rev Helm, developed their 'running mastiff' in the Matabele and Mashona territories of southern Africa, using them as a small pack of four or five to catch pig, to pull down wounded bucks, to worry lions and to track the blood trails of wounded game. Many of these dogs were killed by crocodiles and snakes, as well as by lions. Such dogs had to have pace, power, courage, determination and remarkable agility. A type gradually developed with immense stamina and impressive robustness,severely tested by both climate and terrain.

Dangerous Quarry

In his 'Hunting Big Game in Africa with Dogs' of 1924, the American sportsman, Er M Shelley, wrote: "Dogs are very fond of hunting them (i.e. wart-hogs), but it usually proves disastrous for the dog, for these hogs have two long tusks that protrude far out from the lower jaw, and they use them with deadly effect. Dogs can be maimed or killed much more readily by hunting these hogs than by hunting lions." The early settlers in remote areas of southern Africa faced enormous dangers when hunting for food or protecting their stock. The value to them of brave, determined, powerful dogs is inestimable.

Bushmen's Dogs

Kobben, who arrived in the Cape only half a century after the first settlers under Jan van Riebeeck (1652), noted that the Hottentots used dogs for hunting and protection and that Europeans made regular use of such dogs. Lawrence Green, in his 'Lords of the Last Frontier' (1936) described the bushmen hunting dog as "a light brown ridgeback mongrel...ready to keep a wounded leopard at bay until the master finds an opening for his spear." The ancient Greeks would have admired that. Forty years ago, a game warden reported bushmen's hunting dogs in South West Africa sporting prominent ridges.

Likely Ingredients

Accounts of dogs owned by early Boer farmers embrace breeds such as Bloodhounds, Greyhounds, Bulldogs, Mastiffs, Foxhounds, Pointers, Bull Terriers and Airedales. 'Steekbaards', rough-coated dogs, hinting at Deerhound, Irish Wolfhound, Airedale and continental griffon blood, were favoured by many Boer hunters. Van Rooyen had one, which was killed by a sable antelope. A writer to the Cape Times once gave important clues as to the make-up of these big resolute hunting dogs used by farmers in the bush. The writer stated that when he was a boy (around 1887) his father, like nearly every farmer, kept steekbaard (stiff beard) or vuilbaard (dirty beard) - honde, the size of Greyhounds. The first ridged pups he ever saw, born on his father's farm, were out of a purebred English Bulldog bitch, by a steekbaard sire. All had a distinct ridge of hair along their spines. The sire was a descendant of steekbaard dogs brought from Swellendam, when the trek to the Colesburg district took place. Steekbaards were sometimes advertised as Boerhounds (as distinct from Boerbulls or Boerboels) and occasionally as 'lion dogs'.

Needs of Pioneers

Pioneer farmers needed powerful, determined dogs which would stand their ground when faced by predators such as marauding lions, leopards, wild dogs, jackals, hyenas, baboons, even human rustlers; this demanded the characteristics of the holding dogs, the famed mastiff group, and led to the development of Boerboel type dogs. Farmers also needed faster but equally determined dogs to hunt, running mastiffs by inclination, leading to the development of Boerhounds or lion dogs. In that climate and terrain, against such enemies, only the most virile dogs survived. One writer described the hounds used by farmers as rough-haired Greyhounds. The hunter-writer William Baldwin, mid 19th century, described the hunting dogs he preferred: "bull and greyhound, with a dash of the pointer, the best breed possible." A later book of his was illustrated with a drawing of a 'ridged European dog'.

Imported Breeds

Inspired by Baldwin's book, a hunter called Frederick Courteney Selous travelled extensively until the 1890s, covering most of southern Africa. Later he hunted with van Rooyen, accounts of their dogs mentioning, again and again, rough-haired Greyhounds, Pointers (prized not only for their noses but for the robustness of their feet) and mongrels between these breeds and local dogs. The Bulawayo Chronicle contained the following references to breeds of dog in the period 1894-1917: Pointer (87), Bull Terrier (25), Greyhound (20), Bulldog (19), Airedale (15), Great Dane (14), Boarhound (11) and Deerhound (10). Source: David Helgesen, 1982. Also mentioned were a Cuban Mastiff, a Kangaroo Hound and a 'Ridgeback'.

Selous's Reputation

Selous is forever mentioned by Ridgeback historians but I remain to be convinced about his standing as a hunter with dogs. His book, 'A Hunter's Wanderings in Africa' of 1881, is made up of over 450 pages, more or less his hunting diary of the previous few years. In it he hardly mentions hunting with dogs. He refers to being a guest of the Rev CD Helm, (from whom Van Rooyen bought his dogs), without mentioning his dogs. In his hunting exploits of 1876, he records: "...our mongrel pack. At the mere scent of the lion all but two rushed precipitately past us, not forwards, but backwards, with their tails between their legs, some of them yelping with fright; nor did they put in an appearance again until the hunt was over." He doesn't come across as a dogman at all.

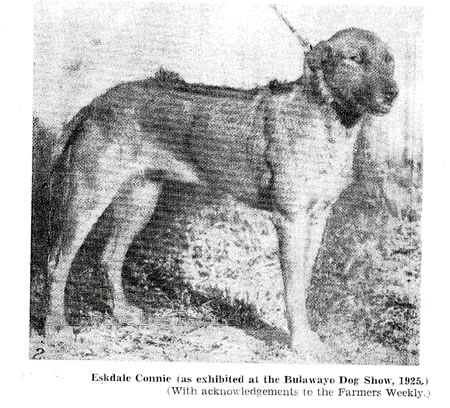

Stabilising the Breed

The first printed use of the word ridgeback for a breed was in a newspaper advertisement of 1912, offering 'Well bred 'Ridgeback' hunting pups for sale.' An English vet, working in Bulawayo, Charles Edmonds, took an interest in these 'ridged lion hunters', as he called them, and suggested classes for them at dog shows, based on a description of: Height 24", weight 60lbs, colour tawny, fawn or brindle, coat short and hard, head rather broad, cheek muscles well developed, in the shape of the old Bull Terrier. That is a fair summary of the phenotype of any prototypal running mastiff. It is interesting to note that in his book 'Hunting Big Game in Africa with Dogs' of 1924, Shelley observes on jackal hunting: "There was a smooth-coated red dog in the bunch named 'Red' that did most of the catching. He was faster than the others and had a good nose."

Recognising the Breed

Another Englishman, Francis Barnes, settled in Salisbury in 1875 and became interested in the breed. He wrote to the national kennel club in 1925, stating that a breed club had been formed for the Rhodesian Ridgeback (Lion Dog) Club. Another Salisbury resident, BW Durham, a Bulldog exhibitor, helped Barnes to produce a breed standard and get the new breed recognised. In 1926, the South African Kennel Union recognised the breed. The Rhodesian Ridgeback is now recognised across the globe, gaining championship status in Britain in 1954 and admission to the American Kennel Club registry in 1955. The English KC correctly places the breed in its Hound Group, something it denies to the Great Dane.

Eastward Movement

Another ridged breed, the Thai Ridgeback Dog, is gaining popularity; a light chestnut red, pure black and silver blue (acknowledged mastiff colours), it is 24" at the shoulder, weighing 60-75lbs, very similar to the African dog. Claims have been made that the African dog descends from a ridged dog, the Phu Quoc dog, found in the Gulf of Siam, with some suggesting a westward movement of such dogs. My view is that it is more likely for the African ridged dogs to have been taken to Asia with black slaves, i.e. an eastward movement. The Arabs were trading slaves to Canton and Siam as long ago as 900AD (Jeffreys, 1953).

Perpetuating Correct Type

Comparable ridges on the backs of dogs have manifested themselves in Weimaraners and a purebred Labrador. Many fawn dogs of mastiff type, as well as Bulldogs and Boxers with red in their coats, have been known to display spinal markings of darker colouration and on hair with a different texture. A few years ago, in New Zealand, two purebred Mastiffs went through quarantine there, each featuring a ridge of reverse hair along their spines. This distinctive feature is however the hallmark of the African and Thailand breeds, with Rhodesian Ridgebacks respected all over the world for their hardiness and character. They may not used as running mastiffs in the classic manner any more but their service to the early settlers, especially the hunter-farmers, was invaluable. A medieval master huntsman like Gaston de Foix would have admired them; they evolved in a tough environment and developed in a tougher school. We must now perpetuate them as famous African hunters designed them to be: hugely capable par force hounds, true running mastiffs. In America, the breed has now been allowed to compete in AKC Sighthound field trials; this could lead to a leggier, lighter-boned hound prized for its speed at the gallop ahead of its stamina and UK breeders need to aware of this change of use.

The Breed Today

The post-show critiques in the last few years reveal the state of the breed in Britain. Comments have varied from concerns about size, condition, poor feet and weak pasterns, variations in type, lack of chest fill and short upper arms (2011), and weak fronts, lack of forward reach, excessive dewlap and heavy lips, gay tails and too much length in the loin (2012) to narrow, apple-domed heads with small, almond eyes, too level a bite and lack of spring in pasterns (2013). I get the impression however that within the breed far too much attention is being given to the fiddle-shaped spinal crown, its shape, size and configuration. One of the best Ridgebacks I have ever seen was born ridgeless but sadly will never be bred from. Breed features matter less than overall soundness; if breed type alone rests on the quality of the crown, this to me is a false value. Over the years I have been impressed by American dogs, such as Rob Norm's Norma, Dagga and Elsa, Talltimbers Ajax and by Swedish tracking champions from the Roseridge kennel of Sonja Nillson. I was immensely impressed by the breathtaking movement of one specimen here a year or so ago: Ch Gunthwaite Midnite Preacha, displaying superb forward and rearward reach and in great condition for a running mastiff.