834 DEER CONTROL - THE STAGHOUND LURCHER

THE STAG LURCHER

by David Hancock

If man wishes to control deer, say in Scotland, the least humane way to do so would be through the introduction of lynx or wolf. Such predators would first kill the young, hampering regeneration. A slow, agonising death by wolf-pack or lynx-attack, for such vulnerable creatures as deer, surely needs to be avoided. Although the know-all metropolitan elite would never concede it, the most humane way for such control, would be for the selected quarry to be pursued, then pulled down by carefully-trained hounds for quick despatch by humane killer. A staghound-lurcher would be an ideal choice for such a much-needed culling. Deerhounds used to go for the hamstring or ear, then pulling down the deer, with no savaging or mauling of the quarry - one clean shot is then a quick end. Big game hunting it is not.

If man wishes to control deer, say in Scotland, the least humane way to do so would be through the introduction of lynx or wolf. Such predators would first kill the young, hampering regeneration. A slow, agonising death by wolf-pack or lynx-attack, for such vulnerable creatures as deer, surely needs to be avoided. Although the know-all metropolitan elite would never concede it, the most humane way for such control, would be for the selected quarry to be pursued, then pulled down by carefully-trained hounds for quick despatch by humane killer. A staghound-lurcher would be an ideal choice for such a much-needed culling. Deerhounds used to go for the hamstring or ear, then pulling down the deer, with no savaging or mauling of the quarry - one clean shot is then a quick end. Big game hunting it is not.

But big game hunting became almost an obsession with some Victorian sportsmen, with some wealthy hunters spending enormous sums and huge amounts of time at this pastime. Sir Samuel Baker describes in his book 'The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon' the use of various dogs in big game hunting. He took a pack of thoroughbred Foxhounds there with him from England, but only one survived a few months' hunting in Ceylon. He favoured, for elk-hunting, a cross between the Foxhound and the Bloodhound, using fifteen couple, supported by lurchers.

Baker stated that the great enemy of any pack was the leopard, which would leap down on stray or isolated hounds and kill them. Baker was fond of 'deer-coursing', the pursuit of axis or spotted deer using Greyhound and horse. He used pure Greyhounds, "of great size, wonderful speed and great courage." A buck could weigh 250lbs and would turn and charge its pursuers, unlike the elk which stood at bay. With some sadness he wrote that "the end of nearly every good seizer is being killed by a boar. The better the dog the more likely he is to be killed, as he will be the first to lead the attack, and in thick jungle he has no chance of escaping from a wound." The boar-seizing or stag-detaining lurcher never received the recognition it deserved.

These words from Lord Ribblesdale's 'The Queen's Hounds' describe what might be termed heavy hounds or hunting mastiffs:

"...a breed of deerhounds were long preserved at Godmersham and Eastwell in Kent, the strain of which went back to Elizabethan days. A good one always pinned the deer by the ear, a criterion of the purity of the strain. They were cream or fawn-coloured, with dusky muzzles, greyhound speed and half-greyhound, half-mastiff-like heads...resembling boarhounds in Snyder's or Velasquez's pictures." Some of today's bull-lurchers closely resemble these dogs. In her 'Bridleways Through History' Lady Apsley wrote that: "Charles IX received a present of some 'great hounds' from Queen Elizabeth, referred to as 'mastiffs' or 'dogues'...used in France for killing wolves after the levriers d'attache les avaient coiffes' (i.e. after the sighthounds got them by the ear).

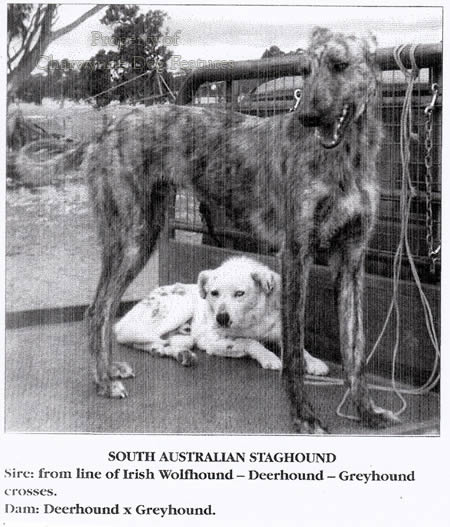

In Old English the word docga referred to a mastiff-like dog and has survived as dogue (French), Dogo (Argentine-Spanish), dogge (German) and dogg (Swedish). The Deutsche Dogge is the Great Dane; the Englische Dogge was famed as a hunting mastiff in medieval Europe. The Saxon word bandogge, used in Middle English, referred to a leashed hunting mastiff, not a tied-up yard-dog. The word mastiff, now mainly used to describe the breed of Mastiff in England, was not in common use until the early 18th century. It was used loosely to describe any huge dog, not a distinct breed-type. The word mastiff is now agreed to derive from an original source meaning of mixed breeding. A staghound-lurcher would be acting as a hunting mastiff. Dogs of this type have been used in Australia as kangaroo-hounds and in America as wolf-hounds. They combine stamina with speed and tenacity with persistence.

Inevitably the loss of function once the hunting of big game with hounds lapsed led to the disappearance of many types of heavy hound: the Bullenbeisser in Germany, the Mendelan in Russia and the Suliot Dog in Macedonia/Greece, for example. The huge staghounds of Devon and Somerset, disbanded early in the last century, were twenty seven inches (0.68m) high and described by Dr. Charles Palk Collyns in his 'The Chase of the Wild Red Deer' as "A nobler pack of hounds no man ever saw. They had been in the country for years, and had been bred with the utmost care for the express purpose of stag-hunting...their great size enabled them to cross the long heather and rough sedgy pasturage of the forest without effort or difficulty."

In his valuable book 'Hunting and Hunting Reserves in Medieval Scotland', John Gilbert writes of references to mastiffs in the Scottish Forest Laws; capable of attacking and pulling down deer, they wore spiked collars and were used to attack wolves and hunt boar, when they hunted to the horn. Gilbert was referring to a heavy hound not what is now the modern breed of Mastiff, whose appearance and especially its movement is scarcely hound-like. This makes a point for me. Directly you stop breeding a dog to a known function, even one long lapsed, then the breed that dog belongs to loses its way. We saw this in the Bulldog and now see it increasingly in the broad -mouthed dogs, worryingly too short in the muzzle and progressively less athletic. Their fanciers forget the sporting origins of their breed, foolishly to my mind, and pursue obsessions with heads, bone and bulk. This is not only historically incorrect but never to the benefit of the dog.

-mouthed dogs, worryingly too short in the muzzle and progressively less athletic. Their fanciers forget the sporting origins of their breed, foolishly to my mind, and pursue obsessions with heads, bone and bulk. This is not only historically incorrect but never to the benefit of the dog.

The mastiff breeds, whether huge like the Mastiff of England, as small as the Bulldog of Britain, cropped-eared like the Cane Corso of Italy and the Perro de Presa of the Canaries, loose-skinned like the Mastini of Italy or dock-tailed like the Boerboel of South Africa, are not only fine examples of powerful but good-tempered dogs but form part of their respective nation's canine heritage. It is vital that they do not fall victim to show ring faddists or misguided cliques of rosette-chasing, over-competitive zealots. Today's breeders need to wake up to such unacceptable excesses, honour the proud heritage of these distinguished breeds and respect them for what they are: the light heavyweights of the canine world, quick on their feet and devastating at close quarter protection when threatened. Such magnificent canine athletes deserve the very best custodianship, with every fancier respecting their hound ancestry, remembering their bravery at man's behest and revering their renowned stoicism. If you want humane deer-control such dogs have a role.