803 REBIRTHING THE MASTIFF-ARRESTING ITS DECLINE

REBIRTHING THE MASTIFF: ARRESTING ITS DECLINE

by David Hancock

A Damaged Breed

A Damaged Breed

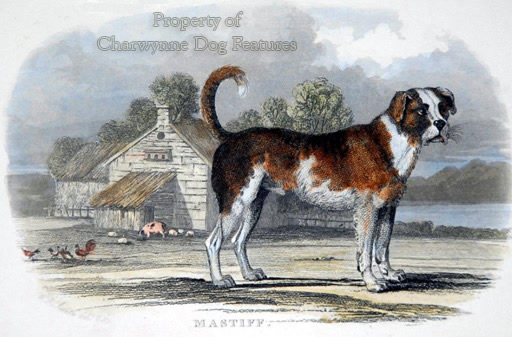

Why did 19th century breeders inflict so much damage on the breed of Mastiff? Why did 20th century breeders continue this regrettable trend? Why are 21st century breeders condoning this and even perpetuating such harm to their breed? Mastiff breeders of today need to ask themselves these questions if the breed they favour is going to survive contemporary welfare and financial pressures. Breed club officials in this very special breed must also be willing to debate whether the breed clubs themselves have, over the years, done as much damage to this famous breed as did the inexplicable use of the seriously-flawed sire Crown Prince in the 19th century. His wholly unsound, totally untypical imprint still lies on the breed. Do today's breeders want a fawn St Bernard (the Alpine Mastiff type, once favoured at Chatsworth) or the descendent of a renowned hunting dog, famed throughout Western Europe four centuries ago for its use as a hound.

"A mastiff is a manner of hound."

'The Master of Game' by Edward, second Duke of York, 1410

Ignoring Origin

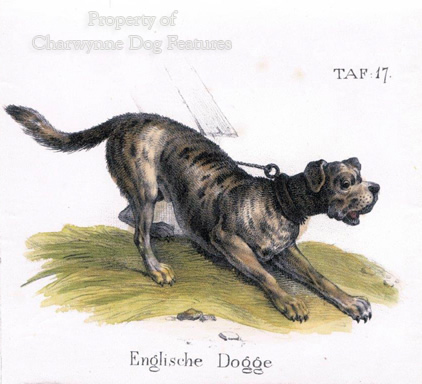

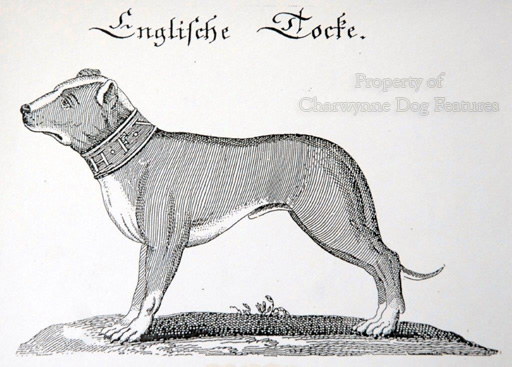

Once breeders either ignore their breed's origin or get misled by false research (or ignorant translators!), then essential breed-type is threatened. The Germans call the Great Dane a German Dogge or mastiff; the consequence must not be square-headed, lower-slung dogs with all their weight on the forehand. Many books on the surviving mastiff breeds tell us plenty about the Deutsche Dogge, or Great Dane, and the French mastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux. But not many tell us the story of the Englische Dogge, most prized hunting mastiff in Central Europe in medieval times. Cox, writing in 1674, described how the King of Poland 'hath a great race of English Mastiffs' which 'are brought up to play upon greater Beasts.' Until the thirteenth century in England, a mastiff-type dog was called a 'docga', an Old English word, still retained on mainland Europe as dogge in Germany, dogue in France, dogg in Sweden and dogo in Spain. The master-engraver Riedinger portrayed the Englische Dogge at the end of the 17th century. In 1836, Hartig was writing in his hunting lexicon that: "The stature of the English Dogge is beautiful, long and gracefully muscular...these dogs are extremely courageous fearing no danger. Most of them are fawn with a black mask." No one claimed them as a breed, dogs then being bred for function not form, and never to a closed gene pool.

Once breeders either ignore their breed's origin or get misled by false research (or ignorant translators!), then essential breed-type is threatened. The Germans call the Great Dane a German Dogge or mastiff; the consequence must not be square-headed, lower-slung dogs with all their weight on the forehand. Many books on the surviving mastiff breeds tell us plenty about the Deutsche Dogge, or Great Dane, and the French mastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux. But not many tell us the story of the Englische Dogge, most prized hunting mastiff in Central Europe in medieval times. Cox, writing in 1674, described how the King of Poland 'hath a great race of English Mastiffs' which 'are brought up to play upon greater Beasts.' Until the thirteenth century in England, a mastiff-type dog was called a 'docga', an Old English word, still retained on mainland Europe as dogge in Germany, dogue in France, dogg in Sweden and dogo in Spain. The master-engraver Riedinger portrayed the Englische Dogge at the end of the 17th century. In 1836, Hartig was writing in his hunting lexicon that: "The stature of the English Dogge is beautiful, long and gracefully muscular...these dogs are extremely courageous fearing no danger. Most of them are fawn with a black mask." No one claimed them as a breed, dogs then being bred for function not form, and never to a closed gene pool.

"The mastiff is a huge, stubborn, ugly and impetuous hound."

'Description of England' by William Harrison, 1586.

Hunting Mastiffs

We talk today of scenthounds and sighthounds, perhaps better described respectively as tracking dogs and those which hunt principally using sheer speed. All hounds use their considerable scenting powers. But at the kill, when big game like bison or boar were hunted, the scenthounds were either not brave enough or were considered too valuable to be risked at such highly dangerous quarry. The life-threatening task of seizing the prey fell to the 'holding dogs', huge determined dogs of reckless courage and immense neck and jaw strength. The expression 'broad-mouth' however should not be confused with a short face; the holding or gripping dogs needed jaw length as well as breadth to seize their quarry. A good title for such dogs would be hunting mastiffs; they are often portrayed in famous paintings of the killing of big game, confusing many Great Dane researchers who see every dog at a boar hunt as a boar hound. The holding dogs or hunting mastiffs (alauntes veutreres) were quaintly described by Gaston de Foix in his Le Livre de la Chasse of 1388: "They are almost shaped as a greyhound of full shape, they have a great head, great lips and great ears, and with such, men help themselves well at the baiting of the bull and at the hunting of the wild boar, for it is natural to them to hold fast, but they are so heavy and ugly, that if they be slain by the wild boar it is no great loss." Breeders of the mastiff breeds today should note that De Foix, the greatest hunter of his day, did not list great bone or a short muzzle in his quite full description.

"...in a pack there may be some individuals which have the special capacity to herd and round up animals for the kill, and others of more massive build who in the main do the attacking. We see the projection of these two types exemplified in our domestic dogs, especially in those of collie type which are pre-eminent as sheep and shepherd dogs, and in those of mastiff type - the massive dogs - which attack the larger animals in the hunt."

The Natural History of the Dog by Richard and Alice Fiennes, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968.

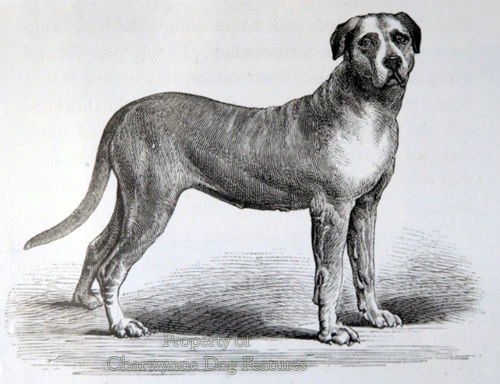

This Mongrel Mastiff

Those wishful thinkers seeking a long and pure ancestry for the Mastiff would be wise to ignore the absurd claims of English Victorian breed enthusiasts and accept that in previous centuries the Mastiff was, in modern terms, a very large mongrel. 'Idstone', writing in his 'The Dog' of 1871, states: "We cannot visit a fair or market in any provincial town without observing this mongrel Mastiff on guard amongst the travellers' carts, generally brindled, frequently blazed...and blended with the Greyhound." In his A General History of Quadrupeds of 1790, Thomas Bewick records: "The Mastiff, in its pure and unmixed state, is now seldom to be met with. The generality of Dogs distinguished by that name, seem to be compounded of the Bull-Dog, Danish Mastiff, and the Ban-Dog." His words should be heeded by those claiming a long and pure ancestry for the modern breed. Such dogs were recklessly brave, many being killed by their quarry. Eventually there came a separation between the running mastiffs or alauntes gentil/veutreres, rather like today's Great Dane and the Dogo Argentino, and the 'killing' mastiffs or matins/mastini/alauntes of the butcheries. The former were par force hounds, used in the chase, the latter were used, rather like the infantry in warfare, to close with and kill the quarry. In France the word 'vautre' was eventually used exclusively for boarhounds. Cotgrave defines the 'vaultre' as "a mongrell betweene a hound and a mastiffe...fit for the chase or hunting of wild Beares and Boares."

"In the very specialised circumstances of the Tudor animal fight, the mastiff was really very much at a disadvantage. It had never been bred, originally, as an animal-fighting dog at all. It was a hunting dog."

'The British Dog' by Carson Ritchie, Robert Hale, 1981.

Mixed Blood

Famous names on early Mastiff breeding records indicate the remarkable mixture behind the breed. The esteemed 'Couchez' was in fact an Alpine Mastiff; Waterman's 'Tiger' was a Great Dane from Ireland. Lukey's 'Pluto' and 'Countess' were reportly 'of Thibet Mastiff' type. The Mastiff breeder HD Kingdon, writing in Webb's Dogs of 1883, mentions "breeders who insist no mastiff has a pedigree of forty years' standing, and who have 'manufactured' for our shows a big cross-bred dog that...has been exhibited ”under the name of mastiff." James Watson, in his The Dog Book of 1906, wrote, and I believe he is quite right, that: "The patent facts are that from a number of dogs of various types of English watchdogs and baiting dogs, running from 26" to "29" or perhaps 30" in height, crossed with continental dogs of Great Dane and of old fashioned St Bernard type, the mastiff has been elevated through the efforts of English breeders to the dog he became about twenty years ago." Those last few words are important; the ‘dog he became’ especially.

Ancestor Blood

An acceptance of that view would allow Mastiff breeders to be more vigilant in watching out for the blood of an ancestor breed coming through too strongly. HD Kingdon wrote, again in Webb's Dogs of 1883: "We do not believe in the purity of mastiffs over thirty inches..." I support that; the universal mastiff type is between 24" and 28" at the shoulder; the flock guarding breeds are bigger and I suspect it is their blood, i.e. that of the smooth St Bernard and the Tibetan Mastiff, which have produced this size increase in the Mastiff. In his British Dogs of 1888, Hugh Dalziel writes that "I do not care to consider whether they were manufactured twenty years ago or have an unspotted lineage from the Flood...although we may produce a fine dog by a mixture of breeds, we cannot have a Mastiff unless that blood is allowed to predominate..." In other words, type matters!

"The breed does not seem to have made the improvements I personally would have liked to have seen it make in the last 15 years or so...I am saddened by the loss of type; where are the square heads, deep broad muzzles and good spring of rib?...I am sure that if we can recapture the old dedication and enthusiasm and watch breeding lines carefully we can return to the breed's former glory. Just because you have a Mastiff that may have won well does not necessarily mean it has to be bred from."

From The Mastiff Today by Lyn Say, Our Dogs, June, 2000.

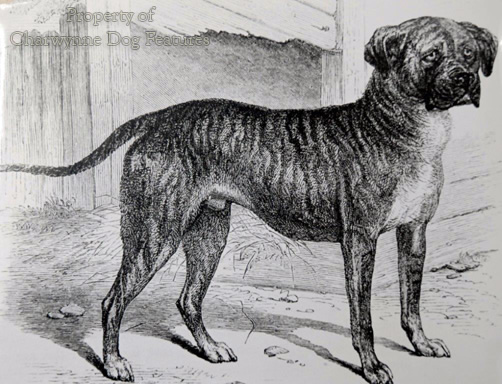

Manifestations of Crosses

The longer coat of the Alpine Mastiff, the Great Dane cranium and the Tibetan Mastiff's upward-curving tail and thicker heavier coat could all surface to the detriment of true Mastiff type. Breed type once lost takes decades of devoted breeding to restore. In his The Practical Dog Book of 1931, the much respected Edward Ash recorded: "In 1867 we read that the Mastiff was being crossed with the Bulldog in order to get a shorter face, for the Mastiff head then was a longer head than was desired. Bloodhounds were also used. The heads became narrow, the eyes sunken and the haw exaggerated." In his The Dogs of the British Islands of 1878, 'Stonehenge' wrote: "A much worse stain in the pedigree of the mastiff is the cross with the bloodhound..." But so many contemporary show ring Mastiffs resemble in outline the early importations of the smooth St. Bernard, only the solid KC-recognised colours reveal the advertised breed. Is this really what the famed Mastiff of England should be like? Is the fawn coat just the colour favoured in the show ring? Why not respect the breed's true gene pool and acknowledge the colours that occur naturally in purebred stock? Why not honour the fine dogs depicted by Bewick, Marshall, Gilpin and others in past centuries?

"In Anglo-Saxon times every two villeins were required to maintain one of these dogs for the purpose of reducing the number of wolves and other wild animals. This would indicate that the Mastiff was recognised as a capable hunting dog..."

'The Complete Book of the Dog' by Robert Leighton (Cassell) 1922.

Ugly Brutes

Concern about the wisdom of breeding Mastiffs to a flawed design is hardly new. Writing on the Mastiff in The American Book of the Dog of 1891, William Wade made these remarks about the Breed Standard cast by MB Wynn: "If you interpret this standard and scale of points with strictness in every particular, and breed to it faithfully, you will get dogs that will be, bodily at least, all you want, and it may be mentally; but if because the scale allots forty points in a hundred to head properties, you magnify that forty to ninety nine, and condone weak loins, straight hocks, too short bodies, weak joints, and frightfully undershot muzzles, as weighing nothing against 'that grand head', you will probably get waddling, ugly brutes that will never rise above the position of prizewinners under 'fancy' judges." Prophetic words! The judge's critique for the Mastiff classes at a 2006 Championship Show started with: "A few quality examples of the breed appeared but the number of untypical specimens with major constructional faults and appalling movement gave much food for thought." In Dog World in September 2009, breed expert Betty Baxter was writing, on the History of the Mastiff: "So what of today? Looking at the dogs in the ring now, so many faults become apparent and the worst of them, to my way of thinking, are the weak hindquarters, straight stifles and lack of width in the second thigh. Hindquarters appear weak, and there is no proper drive and power on the move for many Mastiffs." We need a new Breed Standard and one worded to produce a heavy hound, for that is what our Mastiff truly is.

(First Draft)

BREED STANDARD FOR THE ENGLISH MASTIFF

Phenotypal Word Picture

The Mastiff breed comes from a sporting background, used as a running mastiff in the medieval hunt; once this role lapsed, as the hunting of big game became either a tracking skill, following the development of firearms, or a pack task, the breed lost its founding role and became a guard/companion breed. This breed needs size with strength; it is fundamentally different from the Livestock Protection Dogs, like the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, requiring the bone and bulk to withstand the elements and the long distance walking involved in transhumance. The Mastiff needed muscularity, dash, athleticism and sheer power; it was never bred for beef! The bigger the dog, the greater the need for soundness; a huge hound needs power on the move, great physical coordination, a well-balanced anatomy and should be prized for its muscularity ahead of its height and weight.

The following word picture is designed to honour the breed's first role, a role that shaped both its anatomy and its nature:

Sporting Role: To seize and hold big game, such as auroch, bison, boar and wild bulls.

Working Role: To pin wayward cattle, to drive stubborn stock, to provide support for butchers and cattle farmers; to patrol estates and ranches, detaining poachers and rustlers, to guard property.

General Appearance: A powerfully-built, well-muscled, broad-mouthed but not short--muzzled, short-haired, heavy hound, just over two feet high at the shoulder; coat colour: the dilutions of black (fawn, brindle, red tan, apricot, etc.,) black or black brindle, with white markings, pied - embraced by the gene pool; usually featuring a black mask and muzzle on the lighter coats; active, athletic, symmetrical, formidable-looking and hinting at great power and muscular athleticism. Never over-boned or exhibiting sluggish movement.

General Appearance: A powerfully-built, well-muscled, broad-mouthed but not short--muzzled, short-haired, heavy hound, just over two feet high at the shoulder; coat colour: the dilutions of black (fawn, brindle, red tan, apricot, etc.,) black or black brindle, with white markings, pied - embraced by the gene pool; usually featuring a black mask and muzzle on the lighter coats; active, athletic, symmetrical, formidable-looking and hinting at great power and muscular athleticism. Never over-boned or exhibiting sluggish movement.

Characteristics: Bold, confident and protective, without unwanted aggression, naturally inquisitive, physically and mentally reliable, possessing great stamina yet able to produce bursts of dynamic energy, alert and eager to learn, devoted to its own family but suspicious of strangers, tolerant of other dogs, impressively magnanimous. Not noisy by nature.

Temperament: Mentally stable, utterly trustworthy with children, spirited at times but mainly calm and phlegmatic, showing no sign of shyness or needless apprehension, able instinctively to discern between acceptable human activity and that warranting suspicion. Can be diffident when young.

Aptitude: Willingness to investigate suspicious activity, able to track, prepared to tackle quarry without hesitation but under control, possessing the instinct to seize and hold or 'pin' its quarry.

Construction: Must have the anatomy of a heavy hound, powerful but agile, strongly-made but never heavy-boned in a cumbersome way, really broad in the chest with the ribs carried well back, strong in the neck and powerful in the head, with most of the weight on the forehand, showing appreciable width and ample length in the muzzle. A balanced dog with a low station. Capability of powerful movement apparent.

Forefront: The head was designed for seizing and gripping sizeable quarry, it therefore needs: a jaw with width and length - at least one third of the whole head length, the jaws closing in a scissor bite, with well-formed strong even teeth. The Mastiff should not feature a massive head, with its accompanying whelping problems, undershot jaws, with its tendency to exaggerate itself with each generation, too short a muzzle, with its loss of gripping power and concomitant dentition problems or excessive loose skin on the cheeks and foreface, flews or dewlaps; these are show ring whims not the requirements of a functional holding dog. The 'stop' is appreciable but not too deep or abrupt (associated with cleft palate). The nose is wide, displaying well-developed nostrils; the eyes are full, tight and dark. The ears are soft-leathered, high set, drop, neither large nor pendulous. The neck is extremely powerful, strongly muscled, clean without throatiness, sweeping into the shoulders without coarseness. A low head carriage on the move is characteristic, the occipital foramen, through which the spinal cord emerges, is placed a little lower in the skull in this type of dog.

Forehand: The shoulder blades are long and set well apart; the shoulders are well laid back, sloped to allow the seeking of ground scent without difficulty; the upper arm is of sufficient length to allow good forward extension; the elbows fit closely but the 'elbow slash' controls the degree of forward reach; the forelegs are straight when seen from the front but show a forward slope of pastern when seen from the side, to allow spring when jumping and landing, an important feature in a heavy active dog. The forelegs should not be over-timbered, with strong flat bone preferred to round heavy bone. The feet are oval and sizeable, wolf-like, with strong toes, robust pads and sturdy nails.

Torso: The chest is really broad, deep and well-sprung; the body is compact but with a good length of ribcage; the underline of the abdomen shows discernible but not appreciable tuck-up; the loins are wide, slightly arched and strongly muscled; the topline is level, with the length from point of shoulder to point of buttock being more than the height at the withers.

Torso: The chest is really broad, deep and well-sprung; the body is compact but with a good length of ribcage; the underline of the abdomen shows discernible but not appreciable tuck-up; the loins are wide, slightly arched and strongly muscled; the topline is level, with the length from point of shoulder to point of buttock being more than the height at the withers.

Hindhand: The croup is slightly lower than the withers, falling away gently towards the root of tail. The hindquarters are extremely powerfully muscled, with well let down hocks, a distinct turn of stifle, and straight legs when seen from the rear; The feet are oval - wolflike, compact without being bunched, with strong tough durable pads and sturdy nails, which must not be brittle. The tail has a thick root, not set too high and carried low. A tail which is set on too high indicates too flat a placement of the croup or sacrum, so often accompanied by straight stifles and then the inevitable slipping kneecaps.

Movement: This should demonstrate obvious power, with a strong action, powerful drive from the rear, with minimal leg lift and obvious economy of effort, based on good coordination of front and rear actions. The forelegs must retain separation when moving, so that the dog remains balanced. Heavy dogs should not 'pull' themselves along, but drive themselves along. The heavier the dog then the greater the importance of balance and sound movement, which indicates, more than any human visual judgement, sound construction. Hunting mastiffs had to have the stamina to accompany mounted hunters and the sprinting power to dash forward and seize their quarry, unlike scenthounds which bayed their prey.

Coat: Colour; the dilutions of black, i.e. rich tan, apricot, red, fawn, brindle, with small white markings, usually on the chest. Solid black and pied can occur quite legitimately in the Mastiff, and should be treasured in the pursuit of genetic diversity.

Texture: short, hard, dense; softer on the head and ear leathers.

Size: Height at withers; from 28 inches upwards. Not bred for - ahead of soundness.

Weight; from 100lbs upwards. Always commensurate with height.

Size without soundness has no merit!

Faults: Disqualifying; Obesity (which shortens lifespan and inhibits lifestyle).

Unwanted aggression.

Knitting, plaiting or paddling in the front action.

Over-reaching or weaving in the rear action.

Lack of 'spread' in the chest.

Cow hocks.

Wry mouth.

Visible incisors, when mouth closed.

Serious; Too short a muzzle.

Straight stifles.

Lack of purposeful movement.

Massive heavy bone.

Over-large heads.

Out at elbow.

Angle of the hock too closed.

Others; Too abrupt a 'stop'.

Poor pigmentation.

Splay feet.

Sway back.

Narrow across the hips.

Prominent eyes.

Any degree of haw.

Note: Every attempt has to be made to avoid the long-acknowledged built-in faults in the pedigree stock - dippy backs, straight stifles, limp tails, massive bone, giant heads, over-wrinkling and excessive dewlaps, the presence of haw, poor forward reach and a lack of drive from behind. There should be no exaggeration in any part of the breed's anatomy.

ADDENDUM TO REBIRTHING THE MASTIFF

"He was very fond of hunting and chasing; every morning at one o'clock, surrounded by his huntsmen and horsemen, he went forth...He had with him some English dogs, such as Ball, Turk, Anhalt and the young Weckuff, which later was his favourite and even slept in his bedroom; he was snow-white, with a red spot on the ear and on the back of the head; he was a faithful dog, and what he seized he held."

Wilhelm Buch, writing on Prince Phillip of Hesse, (1505-67).

"Besides the Englische Doggen which are the largest, there are the Baren and Bullenbeisser, which, in comparison with the Englische Dogge, are much smaller, so, in fact, that they can crawl beneath them without touching..."

Heinrick Wilm Doebel, Huntsman Practica, 1746-86.

N.B. This is a discussion document not the finished article. It is intended to offer a comprehensive text for future draftees.