791 MAKING A BRITISH HPR

Making a British HPR - Meet the Striver!

by David Hancock

We British have a remarkable record for developing gundog breeds but almost entirely in a specialist role. We have every reason to be proud of our bird-dogs, our flushing dogs and our retrievers but not for our inability to respond, domestically, to the sportsman's desire for an all-rounder. Indeed, the opposition to them, even in the sporting press, right up until the 1990s, had been almost recalcitrant! Yet, our sporting ancestors, as sporting art reminds us, did use Pointers and Setters to retrieve before convention took over and specialisation ensued. And how long ago was it that we actually bred a gundog for a perceived purpose rather than an inherited method?

We British have a remarkable record for developing gundog breeds but almost entirely in a specialist role. We have every reason to be proud of our bird-dogs, our flushing dogs and our retrievers but not for our inability to respond, domestically, to the sportsman's desire for an all-rounder. Indeed, the opposition to them, even in the sporting press, right up until the 1990s, had been almost recalcitrant! Yet, our sporting ancestors, as sporting art reminds us, did use Pointers and Setters to retrieve before convention took over and specialisation ensued. And how long ago was it that we actually bred a gundog for a perceived purpose rather than an inherited method?

The sport of shooting responds well to more accurate weapons, their longer range and improved ammunition, less well to the changing ways of those who shoot. British servicemen based post-war in Germany, saw the value of the continental all-round gundog and, not afraid to deny convention, brought them home with them. We owe them a great debt of gratitude for their vision, judgement and decision-making. Having myself lived and worked in Germany on three separate occasions, in three quite different locations, I had the opportunity to witness the performance of the native gundog breeds favoured in each area. I never once found an all-rounder, or HPR breed there, with 'a total lack of style' or 'a mouth like a rat-trap', as being alleged here; I didn't find a below-par performance in each gundog 'discipline' and certainly no falling-away of gundog standards - quite the reverse. I found myself observing German gundog breeds that had admirable physical soundness, backed by open-minded breeders and enviable breeding controls. I was smitten by the all-round excellence of the dogs and, especially, by their field performance.

I admired the sheer efficiency of the German pointers, was not surprised when the GWHP and its short-haired cousin became sought after here, but found the elegant stylish Langhaars equally impressive, especially in Holland. I liked the enthusiasm of the Munsterlanders, large and small, and the keen work of the hound-like Weimaraners. I found it difficult to distinguish between the Stichelhaar and the GWHP and between the Korthals Griffon, so effective in flooded areas and in denser cover, and its Czech equivalent, the Cesky Fousek. In Britain we haven't taken so eagerly to the griffon type either in hounds or gundogs. I had never seen a British gundog with the drive and urgency of purpose as one particular Korthals Griffon.

This never meant that my fondness for our native breeds was reduced but it did arouse my surprise at the lack of any interest in producing a home-grown all-rounder. When you consider the British gundog material available to any British equivalent of say Korthals or von Zedlitz (who produced the Pudelpointer) who developed their own gundog for a local need, we either saw no need to develop an all-rounder here or lacked the will. But, then, even American sportsmen use imported all-rounders and, despite claiming the Chesapeake Bay Retriever (our native Norfolk Retriever relocated to Norfolk, Virginia), their own water spaniel (as we lost ours) and persevering with the Llewellin Setter, never went for all-round skills in their native dogs. Their hound breeds seem limitless; their gundog breeds seem limited. Yet there may well be more HPRs in North America than in Germany. But where is the Chesapeake Bay Pointing Spaniel!

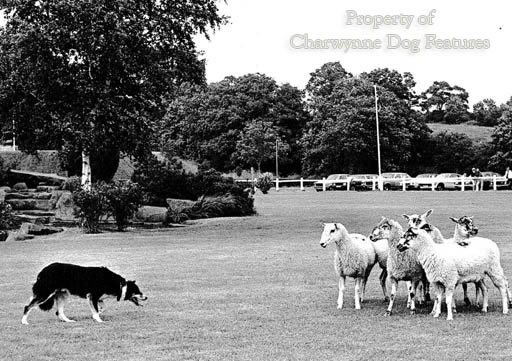

It's usually inspired individuals who introduce change. That classic iconoclast, the late Brian Plummer, (who not only developed the breed of terrier named after him, but defying convention bred pure white Beardies as working dogs and hunted a small pack of Cavaliers!) once told me, perhaps harshly, that he disliked what he called 'the constant seeking of reassurance' of most gundogs. But, loving a challenge, he would have relished the task of developing a British HPR. But what might have been his chosen ingredients? I once had two farm collies that excelled as markers, finders, flushers and carriers. They may have lacked sheer style but their cleverness, enthusiasm and immense determination made them more than useful. I once worked with a ghillie-turned-soldier who told me, very quietly, that the best dog 'on the moors' he ever had was a local 'colley-dog'. I could well believe it; collies were once widely used on Scottish estates in the deer-stalking role.

So, seeing the collie's 'header-stalker' prowess as a setting and pointing asset, I would include collie blood in any of my British HPR breeding plans. This would give me a head start in biddability too. The best natural retriever I ever saw at a working test was a Curly-coated Retriever - so badly handled he never went on. But here would be the weatherproof coat and the innate desire to retrieve. But what about scenting skills? A West Country hound expert once told me that the best hound on ground scent he ever saw was a black and tan Tiverton Foxhound. You only have to study the Kerry Beagle, the Bloodhound, the old Dumfriesshire Foxhounds and the Swiss, Scandinavian, Baltic and Balkan scenthounds to see the link between this coat colour and good scenting. A black and tan HPR would be most distinctive.

But what about air-scenting? We have a black and tan setter in Britain, the under-used, under-rated Gordon Setter, although the Duke himself preferred tricolours. I have only seen one top-class Gordon, but that was in Italy and owned by an Italian Colonel in the Alpini. But most of this breed are over-coated for field work, although when they have a good coat it's really good. Surely a blend of setter, retriever, hound and sheepdog could produce a strongly-performing gundog - but what would it be called? Such a dog would need to seek, track, respond, indicate, verify (with its handler), evaluate (as sheepdogs do every day in the pastures) and recover (shot game). That list deserves an acronym! Look at the first letters in each key word and it spells Striver. We had the dropper; we have the setter and the pointer. Now we could have the Striver, our all-new national HPR breed! I warm to dogs that strive! No demand for a British HPR? Keep in mind that in 1980, a grand total of 1,888 HPRs of all breeds was registered in that year by the Kennel Club; in 2010, just 30 years later, it had more than trebled. We are more adventurous than we think! Now we need to match that sense of adventure with ambition - an ambition to produce a British HPR that would be a world-beater.

But what about air-scenting? We have a black and tan setter in Britain, the under-used, under-rated Gordon Setter, although the Duke himself preferred tricolours. I have only seen one top-class Gordon, but that was in Italy and owned by an Italian Colonel in the Alpini. But most of this breed are over-coated for field work, although when they have a good coat it's really good. Surely a blend of setter, retriever, hound and sheepdog could produce a strongly-performing gundog - but what would it be called? Such a dog would need to seek, track, respond, indicate, verify (with its handler), evaluate (as sheepdogs do every day in the pastures) and recover (shot game). That list deserves an acronym! Look at the first letters in each key word and it spells Striver. We had the dropper; we have the setter and the pointer. Now we could have the Striver, our all-new national HPR breed! I warm to dogs that strive! No demand for a British HPR? Keep in mind that in 1980, a grand total of 1,888 HPRs of all breeds was registered in that year by the Kennel Club; in 2010, just 30 years later, it had more than trebled. We are more adventurous than we think! Now we need to match that sense of adventure with ambition - an ambition to produce a British HPR that would be a world-beater.