790 SHEPHERDS DOGS & AND NEW

SHEPHERDS’ DOGS OLD AND NEW

by David Hancock

“The group in which the sheepdogs are included is characterised by a high order of intelligence. In order that their duties may be performed creditably they must be sensible, tractable and hardy. Besides learning readily the lessons that are taught them at an early age, they must acquire certain powers of initiative that are shown sometimes in a form so remarkable as to make one wonder if psychologists are justified in denying the faculty of reasoning to dogs.”

“The group in which the sheepdogs are included is characterised by a high order of intelligence. In order that their duties may be performed creditably they must be sensible, tractable and hardy. Besides learning readily the lessons that are taught them at an early age, they must acquire certain powers of initiative that are shown sometimes in a form so remarkable as to make one wonder if psychologists are justified in denying the faculty of reasoning to dogs.”

From About Our Dogs by A Croxton Smith, Ward, Lock & Co., 1947.

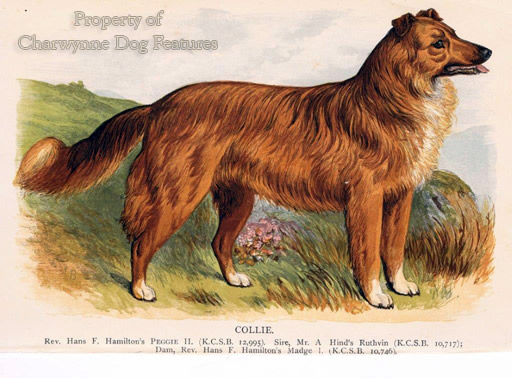

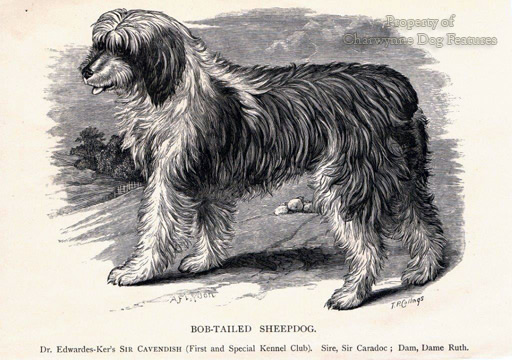

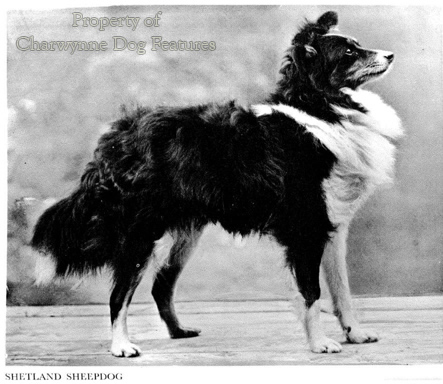

In 1908 there were just six pastoral breeds on the Kennel Club’s list of recognized pedigree dog breeds: Collies Rough and Smooth, Old English Sheepdogs, Shetland Sheepdogs and Welsh Corgis, plus the ‘Alsatian Wolf Dog’. In 2013, there were 31 – the biggest number of breeds in any of the KC’s Groups - although perversely the KC places pastoral breeds like the Hovawart, the Beauceron, the Bouvier des Flandres and the Swiss mountain dogs in their Working Group. It is worth a glance at these ‘dogs of the shepherds’ to see their widespread use across the globe, showing the immense value of such dogs to man: the Anatolian Shepherd Dog and the Kangal Dog (from Turkey); the two Australian breeds – their Cattle dog and their Shepherd Dog; the Bearded, Border, Rough and Smooth Collies, the Old English and Shetland Sheepdogs, the Lancashire Heeler and the two Welsh Corgi breeds, all from Britain; the four breeds of Belgian Shepherd Dog; the Briard from France and the Catalan Sheepdog from Spain, with the two Pyrenean breeds – Mountain Dog and Sheepdog and the Maremma Sheepdog of Italy coming from adjacent countries; the three Hungarian breeds: Kuvasz, Komondor and Puli; the Estrela Mountain Dog from Portugal and finally those from much further north, the Polish Lowland Sheepdog, the Norwegian Buhund, the Finnish Lapphund, the Samoyed, and the Swedish Vallhund.

Most of these originated overseas, but, because of its wide-ranging capabilities, our native breed - the Border Collie, once never even considered as a pedigree dog, attracts over 2,000 new registrations - our most favoured native pastoral breed. The German Shepherd Dog, however, totalled over 8,000, as our love affair with breeds from overseas showed itself again. Far too many of our native pastoral breeds are under threat of extinction in this century, with breeds like the Smooth Collie, the Cardigan Corgi and the Lancashire Heeler each only attracting around 100 new annual registrations each year.

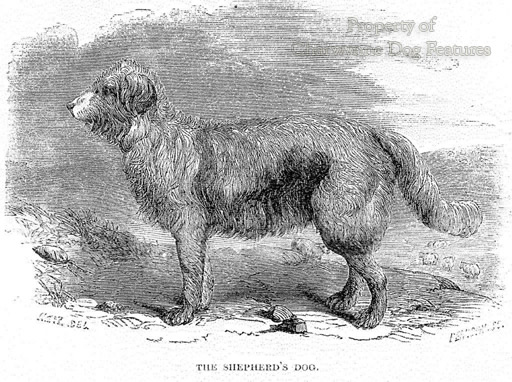

Never listed by the KC were the Smithfield Sheepdog (a leggy, shaggy-coated drover’s dog), the Blue Shag of Dorset (a mainly blue-grey bob-tailed sheepdog), the Welsh Hillman (the longer-legged uplands sheepdog of Wales), the Old Welsh Grey (the bearded sheepdog of Wales), the Welsh Black and Tan Sheepdog (the shorter-coated ‘valleys’ sheepdog of South Wales), the Galway Sheepdog of Southern Ireland (a big tricolour dog – resembling the Bernese Mountain Dog) and the Glenwherry Collie of Antrim (a mainly merle or marbled type, often wall-eyed), each one a distinct type, however little known outside their favoured areas. Every year, the use of pastoral dogs declines a little further, as modern pressures alter our agricultural methods and the urban sprawl continues. But every year it seems a new use is found for that talented breed - the Border Collie, as its sheer versatility and wide range of skills find employment. It is now the case that many pastoral breeds are, more often than not, unlikely to be utilised in the pastures and far more likely to be employed as service dogs, with the military, the police and search and rescue organisations. They are still valued; they can still do things that humans cannot.

The international kennel club, the Federation Cynologique Internationale (FCI) lists quite a number of pastoral breeds in their Group 1 that are not recognized by our KC: the Picardy Sheepdog, the South Russian Sheepdog, the Croatian Sheepdog, the Dutch Shepherd, the Mallorquin Sheepdog, the Portuguese Sheepdog, the Kelpie, the Schapendoes, the Hungarian Mudi and Pumi but put the flock-guarding breeds like the Anatolian Shepherd Dog, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, the Caucasian Sheepdog, the Estrela Mountain Dog and the Hovawart into a separate Group, 2. This does not help the allocation of judges from England to their shows or the reverse; judges need to appreciate role, the function that led to the design of the breed. Herdingfdogs need a very different anatomy from the mountain dogs or flock protectors and the rating of such physical points deserves specialist knowledge and judgement.

The FCI also recognizes foreign breeds in this Group quite unknown in Britain: the Cao de Castro Laboreiro and Rafeiro do Alentejo from Portugal, the Karst and Sarplaninac from the former Yugoslavia and the Central Asian Sheepdog. As, especially in countries that emerged from behind the ‘Iron Curtain’, more native pastoral breeds are ratified, this process will continue. Breeds such as Roumania’s Mioritic Shepherd, the Bucovina Shepherd, the Carpathian Shepherd and the jet black appropriately-named Raven Dog have been presented at the country’s shows for the first time. In Western Europe too, native breeds are becoming recognised as the canine heritage of each nation is at last being valued by the show fraternity; in Spain for example at the 2013 Madrid show, the Garafino Sheepdog (from the Canary Islands) was paraded, then three other native breeds, the Carea Leones, the Carea Manchego and the Euskal Artzain Txakurra were introduced to the curious onlookers in the main ring programme. In this book, I aim to cover many of these, but because their function was the same as the pastoral breeds already recognized, their physical form is remarkably similar to the better-known herders and flock guardians.

Unlikely to survive a lack of recognition and failing interest in the pastures are the brindle Cypro Kukur or Kumaon Mastiff of Northern India, the Cane Garouf or Italian Alpine Mastiff or Patua, and the Corsican native livestock protection dog, the Cursinu, resembling the Karst. The little Croatian heeler the Medi is now being promoted, the Portuguese (Azores) version of our Old English Sheepdog: the Barbado da Terceira, the huge Cao de Gado Transmontano of North Portugal, quite similar to the registered Rafeiro da Alentejo, and the Chodsky Pes, a Czech herding dog rather like a smaller Tervueren, are all attracting interest at long last. Meanwhile, as ever, zealous individuals are at work, promoting newly-developed breeds like the Panda Shepherd in Canada, a GSD with a very specific coat colour, the King Shepherd and Shiloh Shepherd in America - ‘improved’ GSDs, the Swiss Shepherd – an all-white GSD that is gaining support in Switzerland, with the Welsh Mountain Dog being promoted in the Principality. It is noticeable that in several countries the GSD is being ‘improved’ by dissatisfied fanciers of the show GSD in the 1990s style of that dog. The recently-developed Eastern European Shepherd, an attractive, more traditional GSD-variant, became Russia’s most popular breed.

In this book, I aim to make a case for the origin and function of all pastoral types, ancient and modern, to be respected, not in the pursuit of historical accuracy, important as that is, but because they can only be bred both soundly and honestly if their past development and traditional form is honoured. Their original lowly rural breeders have left these magnificent canine servants to us and we have a duty of care towards these impressive and quite admirable breeds of dog. There is less research material on the dogs of the shepherds than say on sporting dogs such as gundogs and hounds. Both the latter types were owned and patronised by the wealthy and better-educated, the former usually by illiterate agricultural workers. This increases my resolve to do them justice after centuries of neglect. My personal affection for this type of dog rests on the thirty-odd years of loyal yet stimulating companionship that I was given by my own working sheepdogs, perhaps better described as unregistered Border Collies; they taught me an enormous amount about dogs – and quite a lot about myself.

“The sheepdog is so completely absorbed in what seems the sole business and employment of his life, that he does not bestow a look, or indulge a wish beyond the constant protection of the trust reposed in him, and to execute the commands of his master; which he is always anxious to receive, and in fact is invariably looking for by every solicitous attention it is possible to conceive. Inured to all weathers, fatigue and hunger, he is the least voracious of the species, subsists on little…the sagacity, fidelity, and comprehensive penetration of this kind of dog is equal to any other, but that there is a thoughtful or expressive gravity annexed to this particular race, as if they were absolutely conscious of their own utility in business of importance, and of the value of the stock so confidently committed to their care.”

From The Sportsman’s Cabinet of 1803

(this serial is taken from David’s Dogs of the Shepherds to be published in 2014)