789 THE NATURE OF THE GUNDOG

THE NATURE OF THE GUNDOG

by David Hancock

“Mr TA Knight, in a paper addressed, some years ago, to the Royal Society, remarks: “…A young spaniel, brought up with the terriers, showed no marks of emotion at the scent of polecat, but it pursued a woodcock, the first time it saw one, with clamour and exultation; and a young pointer, whom I am certain had never seen a partridge, stood trembling with anxiety, its eyes fixed, and its muscles rigid, when conducted into the midst of a covey of these birds. Yet each of these dogs is merely a variety of the same species, and to that species none of these habits are given by nature. The peculiarities of character can, therefore, be traced to no other source than the acquired habits of the parents, which are inherited by the offspring, and become what I call instinctive hereditary propensities.”

“Mr TA Knight, in a paper addressed, some years ago, to the Royal Society, remarks: “…A young spaniel, brought up with the terriers, showed no marks of emotion at the scent of polecat, but it pursued a woodcock, the first time it saw one, with clamour and exultation; and a young pointer, whom I am certain had never seen a partridge, stood trembling with anxiety, its eyes fixed, and its muscles rigid, when conducted into the midst of a covey of these birds. Yet each of these dogs is merely a variety of the same species, and to that species none of these habits are given by nature. The peculiarities of character can, therefore, be traced to no other source than the acquired habits of the parents, which are inherited by the offspring, and become what I call instinctive hereditary propensities.”

From Cassell’s Popular Natural History, 1890.

“The dog-show setters are most beautiful creatures, but the points on which they win here and in America are not the points that a sportsman requires. Slack loin is only a drawback at the shows but it stops a dog in work. A long refined head is a beauty at the shows, but it holds no brains that amount to anything…To be induced to range they must be excited. Now, in the truly bred pointer or setter you may start by repressing, go on by directing, and end by many ‘dressings’, but you cannot weaken the hunting instinct, however hard you try.”

From Teasdale-Buckell’s The Complete Shot of 1907.

Nurturing Their Innate Character

Books on training dogs a hundred years ago, especially on training dogs for the gun, often contained the word 'breaking' in their title. Some of the latter included such classics as: Dog Breaking by General Hutchinson (1909), Dog Breaking by 'Wildfowler' (1915) and Breaking and Training Dogs by 'Pathfinder' and Dalziel, a little earlier. The trainer is called the breaker in such books and a trained dog is described as 'broken'. Although words can change their meaning over the years, I have always felt considerable distaste over the use of the verb 'to break' in dog training; it suggests training by overt bullying. In Youatt's The Dog of 1854, he wrote: "The cruelties that are perpetuated on puppies during the course of the education or breaking-in, are sometimes infamous."

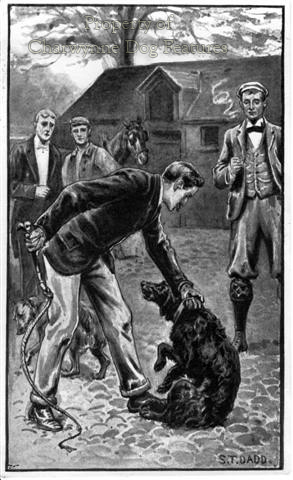

I was therefore pleased to see, in the preface to the 1908 edition of Hutchinson's book, these words by his son: "It is far less common than it used to be to see a dog brutally ill-treated, and I venture to think that the principles inculcated by my father in these pages have gone far to create a more intelligent sympathy between man and dog." The harm of course had already been done, with whole generations of sportsmen and indeed ordinary dog-owners believing that the expression 'dog-breaking' meant exactly that: breaking the dog's spirit. Yet in areas of dog use where the dog is expected to excel the dog's spirit is rightly considered to be of huge importance. It is vital with gundogs to nurture their innate character.

Steady Temperament

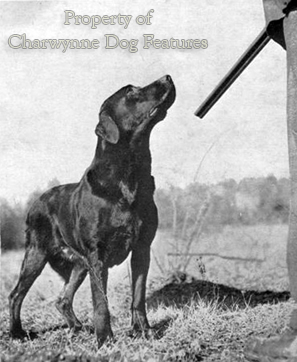

In her most informative book Advanced Labrador Breeding (Witherby) of 1988, experienced show and field breeder, Mary Roslin Williams, stressed the combination of construction and temperament in gundogs for functional performance. She put build and temperament as the first things to be looked for, linking the two together, pointing out that it’s no good having a dog of speedy agile build if the mental ability and game sense is missing. She accepted the need to sacrifice some of the solidity of the show dog, whilst keeping the correct breed type, but removing all traces of lumber, or cumbersome movement. She wanted a dog to be free-moving and agile, but essentially biddable, looking at you during training, neither feckless nor rowdy. She pointed out that the show ring can demonstrate both freedom of movement and steady temperament, if the judging is wise and enlightened. These are important features in a gundog for shooting men.

Importance of Individuality

Many books on training gundogs tell you how to train the dog for a task but rarely advise on individual dogs, dogs with great potential but a wayward reaction to being taught a skill. In his The Scientific Education of Dogs for the Gun of 1920, gundog training expert ‘HH’ wrote: “You must study your pupil’s disposition and general character; if he is open-hearted, bright, and has great courage, you can afford to educate highly, but if he is the least shy, sulky, or indifferent, let it alone or you will spoil him for the real business; indeed, the moment that you observe the least ‘slackness’ in anything, drop it at once, at all events for a time.” Most gundogs are willing, responsive and nice-natured; but it is wrong to think of every member of a gundog breed having the predictable expected temperament of that breed. Some wayward individuals when young have become quite outstanding performers when mature. The skill of the gifted trainer is in acknowledging individuality. One ‘size’ of temperament does not fit all!

Man-Dog Rapport

The same dictum does of course apply to man! As Badcock wrote in his perceptive The Early Life and Training of a Gundog of 1931: “Dogs vary in their natures very much like humans do. What does not change, and what so much endears them to us, is that their moods never vary. They always adapt their moods to the company they are in…It is this that makes them such charming companions, and is why incompatibility of temper between a man and his dog should never occur.” I have been out shooting with a man so soft-natured and indecisive that his dog disgraced him (and itself); it was confused and ill-directed. I have been at a working test where the behaviour of a handler disgusted everyone present; even his dog looked embarrassed! The behaviour of dogs can so often reveal the temperamental failings of their owners. The rapport between man and gundog is key. As Badcock advised: “Only your own intelligence will help you in matters such as these. In all things remember that if a dog fails, search yourself and your own methods first before putting the blame on him…”

Bench and Field Control

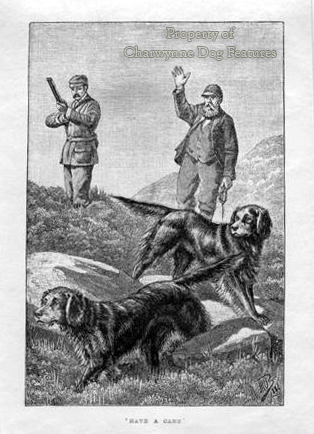

It is never easy to judge a gundog’s potential in the show ring, where it’s controlled by collar and lead, and its field future – an environment where control is imposed on a free-running dog. Dogs over-schooled for the ring can feel lost when let off the lead – as far as control is concerned. As ‘Pathfinder’ and Hugh Dalziel wrote in their Breaking and Training Dogs of 1906: “So far as show-rings themselves are concerned, they are useless for testing even the elements of intelligence possessed by any gundog – Retriever or other wise. Apart from the restricted area in which the judging takes place, the dogs themselves are, by Rules which are imperative, still further restricted in action by chain and handler.” They went on to suggest quite separate intelligence-testing off the lead, to examine the dog’s ability to think for itself. A gundog needs this capability as well as a good memory and great drive, based on sheer determination and natural zest, never linked to any sign of aggression; a gundog with unreliable temperament is more than a menace.

Problems of Aggression

Dr. Roger Mugford, the distinguished consultant in animal behaviour, compiled a table of his cases involving dogs with serious problems of aggression. It showed that of Britain's most popular four breeds, three topped the league for unwanted aggression; two of them were gundog breeds, the Labrador and the red-gold Cocker Spaniel. But the Golden Retriever came sixth and the Irish Setter eleventh; the Dobermann came twelth. The savage unpredictable behaviour found in far too many golden Cocker Spaniels has been traced back to four show champions which were extensively bred from and their offspring exported. Thirty years ago when I was researching their native breeds in Portugal, a local dog owner complained bitterly about his "English spaniel" which had bitten his little daughter quite badly. I asked him if it had been a golden Cocker and he looked surprised at my knowing not just the breed but the coat colour involved too. The "rage syndrome" has been known for some time in golden Cockers but not often publicly acknowledged.

As Dr Mugford has scornfully pointed out: "Very little thought is given to the physical well-being or temperamental characteristics of pedigree dogs so long as their ears point in the right direction". Much of the aggression found in dogs is rooted in fear--perhaps in humans too! The Germans used to label such dogs on their show benches with the warning notice "Angstbeisser" or biter from anxiety. The honorary secretary of the British Veterinary Association once stated that: "If the judges at dog shows, when they see a nervy, snarly dog, no matter how beautiful, said, 'Sorry, we're not looking at him', that would be the end of it." But of course show ring judges lack the moral fibre to do just that and so "angstbeissers" win prizes and are bred from. The late Dr Malcolm Willis, in his time, the leading canine geneticist in this country (once foolishly expelled from membership of the Kennel Club) once stated that "The Kennel Club could force judges to be more careful about character but they don't. When they say they can't do anything, it means they don't want to do anything." The Kennel Club expects breeders to shoulder all responsibility and impose discipline on themselves. But just as the KC needs registration fees income, breeders need puppy sales and stud-fee income. The owner of a Golden Retriever stud dog was once informed that his dog carried and transmitted an inherited disease affecting the brain; he refused to cooperate with his own veterinary surgeon, who, quite naturally, wished to contain the disease. The veterinary surgeon is under no legal obligation to report such an incident and all this stud dog's progeny can be registered with the KC. Who is going to stop such human folly?

Unwise Breeding

Once they reach sexual maturity, bitches can have two litters a year. If a bitch with a genetic defect has only four offspring a year, of which half are female, she could produce (and infect) well over 4,000 descendants in only seven years. Since show champions are not checked for behavioural defects and extensively bred from, we are creating wholly undesirable and quite needless problems for future dog owners. We say we love our dogs but surely we really do love our children; who is protecting them from dogs bred to a cosmetic design but not for mental stability? Unpredictable unstable Rottweilers are produced by irresponsible breeders but so are unreliable golden Cockers and the general public don't know. A dog's pedigree and its registration with the Kennel Club is simply meaningless in terms of quality.

Battersea Dogs' Home receive over 600 abandoned gundogs each year. We know that a quarter of all dogs taken to vets for destruction are taken there for behavioural reasons. How many of the abandoned gundogs had behavioural problems? Inherited behavioural problems can destroy the reputation of a breed faster and more lastingly than any inherited physical defect, as Rottweiler breeders have learned to their cost, (10,000 registered in 1989, under half that number in 1998 and around 6,500 a year more recently). If we really care about dogs, the remedy is simple: all stud-dogs with suspect temperament must be castrated, all breeding bitches with suspect temperament must be speyed. The Kennel Club must deregister any pedigree dog guilty of biting someone in unjustifiable circumstances and its past progeny, not just its future offspring. Sadly I cannot see that happening.

Popularity Penalty

It is a noticeable feature of statistics on breeds afflicted by hereditary defects that the most popular ones head the incident list proportionately and the less numerous breeds feature the least. In a wide-ranging Canadian study, Golden Retrievers were 7th in the list of most-afflicted breeds and 6th in the popularity stakes. Least cited breeds were the German pointers, Welsh Springers, wire-haired Vizslas and Field Spaniels, none of which are over-bred. The same survey indicated that problems of temperament in Labrador and Golden Retrievers were far more prevalent than in the much less popular Curly-coated Retriever. Problems of temperament in English Springers, Irish and English Setters were far worse than in the less numerous Clumber Spaniel.

Dr. Victoria Voith from the USA, who has studied mental illness in companion animals, has linked boredom and lack of employment with unacceptable aggression in dogs. Disturbed dogs that wreck the interior of cars could be fighting boredom. A potential pack-leader lacking exercise may try to impose his will on members of his human family out of pent-up frustration. Both types need the working outlet to expend unused energy and undoubtedly have a spiritual need to carry out the function in the field they were purpose-bred to fulfil. Is it therefore fair to have as a companion-breed a gundog which is never ever required to work? Is it reasonable to buy a powerful energetic 'supercharged' Labrador with field trial champions behind it only for it to spend most of the day sitting on a doormat in the yard of a suburban house?

Danger of Complacency

Half a century ago, when I was working in Germany, the little German dog of one of my many German neighbours was savagely killed by the big English dog of one of my few English neighbours. The latter dog was a black Labrador - with hard, cruel eyes and the head of a Rottweiler. Relating this does not diminish my admiration for the breed of Labrador. Breeds don't misbehave; individual dogs do, partly through their breeding and partly through their upbringing and lifestyle. We can do something about all three if we address this problem. But, as usual with dogs, it'll end up being someone else's problem. I am constantly amazed when highly intelligent parents go out and buy a puppy to live with their family without one single check on its likely temperament. Such parents can spend hours verifying the safety features of the next car; both cars and dogs can harm children if safety checks are not made. We are all being far too complacent about the temperament of our gundog breeds; it is not in their nature to be sharp-tempered.

“The explanation why the average collie is better trained than the average sporting dog is not far to seek. More work is put on him, but so gradually, that his brain can absorb and remember – he is kept up to the mark by having to do certain things daily, and not allowed to forget; he is not taken on a string half a dozen times a year and expected to do a dozen different things of which he never learned the rudiments.”

From The Keeper’s Book by Sir Peter Jeffrey Mackie, Foulis, 1924.

“There is so much that is paradoxical in the mentality of the modern-day shooting man that it is difficult to know what he expects of his dog. He will spend vast sums on a shoot and rearing a large head of game. He will give over £200 for a pair of guns, blaze away hundreds of cartridges at a shooting school to perfect his shooting, and give a long price for a dog only to ruin it in the first half-hour simply and solely because in the art of understanding a dog’s mind he is himself totally uneducated and probably worse.”

Lt.Col.GH Badcock, writing in his The Early Life and Training of a Gundog, Watmoughs Ltd., 1931.

“A good shrill whistle, a good stout whip, a check cord and spiked collar for emergencies, and a plentiful command of language, and the thing is done. Is it? Follow this system and succeed in your object, and in nine cases out of ten you get a sulky slave, a senseless automaton, a mechanical apparatus. It may serve its turn, do its business as long as no complication occurs, but the moment you want something out of the common, presence of mind, thought, or great courage and perseverance, you are nowhere.”

‘HH’, writing in his The Scientific Education of Dogs for the Gun, Sampson Low, 1920.