787 THE CHANGING FORTUNES OF OUR HARRIER

THE CHANGING FORTUNES OF OUR HARRIER

by David Hancock

“What is a harrier? Well, the encyclopaedia tells us that it is ‘the English name for the hound used in hunting the hare’, and it would be difficult to give a more definite description, for he would be a bold man who would undertake to say that there is now-a-days a distinct breed of this nature in the United Kingdom, nor is it worth while to inquire whether there ever was such a breed…many packs consist entirely of dwarf fox-hounds, that being the simplest, most expeditious, and probably the cheapest method of getting and keeping together a ‘cry of hare-dogs’.”

“What is a harrier? Well, the encyclopaedia tells us that it is ‘the English name for the hound used in hunting the hare’, and it would be difficult to give a more definite description, for he would be a bold man who would undertake to say that there is now-a-days a distinct breed of this nature in the United Kingdom, nor is it worth while to inquire whether there ever was such a breed…many packs consist entirely of dwarf fox-hounds, that being the simplest, most expeditious, and probably the cheapest method of getting and keeping together a ‘cry of hare-dogs’.”

Those slightly patronising words from the Duke of Beaufort in his Hunting of 1894 quickly illustrate the lack of recognition of the Harrier over the last century or so. That lack of recognition may be rooted in a lack of identity. In his Hounds in Old Days of 1913, Sir Walter Gilbey wrote: “It is impossible to dissociate the harrier from the stag- or buck-hound, for the sufficient reason that they were the same breed. For hundreds of years, down to the present time, the same hounds have hunted stag, buck and hare; the Anglesey harriers and the Scarteen black and tan beagles in Ireland, for example, hunt both hare and deer at the present day.”

Lack of Recognition

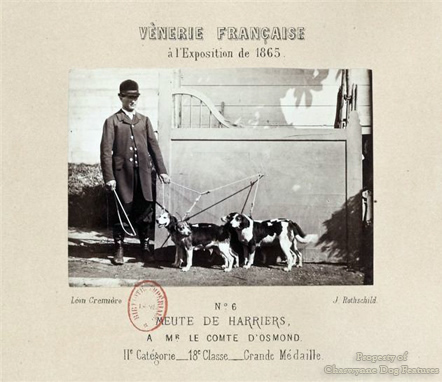

The Foxhound, the Beagle and the Basset Hound are recognized as breeds by the Kennel Club but not at the moment the Harrier. This has not always been the case. Four were registered with the KC in 1913 and 20 in 1925. At the Armagh Dog Show in 1892 the Harrier judge reported in The Kennel Gazette in December of that year that: "Harriers had six couples, all from the same kennel. They were a very even lot..." The KC does however recognise hare-hounds from abroad as the Hamiltonstovare, the Basset Fauve de Bretagne, the Segugio Italiano and the two Basset Griffon Vendeen breeds demonstrate. The American Kennel Club does recognise our Harrier, to me a sad reflection on our custody of native breeds. But the fortunes of the Harrier have always varied. If you take for example the chronology of hare-hunting in just Surrey and Sussex from 1738 to 1925, it shows that 24 packs of Harriers either disbanded, merged or changed to another breed in that period, a period when hunting was an obsession rather than a pastime. This rate of change has rarely been matched in other breeds of packhounds.

In his The Dogs of the British Islands of 1878, Stonehenge alias JH Walsh, wrote on this breed that: "In the present day it is very difficult to meet with a harrier possessed of blood entirely unmixed with that of the foxhound...Breeders still take special care to have a combination of intelligence and high scenting power sufficient to meet the wiles of the hare, which are much more varied than those of the fox..." He also referred to a Rough Welsh Harrier stating that it "still exists in a state of comparative purity"; another native breed neglected to the point of extinction.

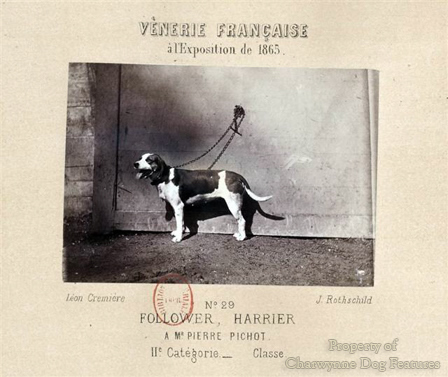

In his The Illustrated Book of the Dog of 1879, Vero Shaw writes on the breed: "It is as a dwarf Southern Hound that the Harrier should be most properly regarded...One peculiarity, however, which distinguishes a Harrier from a Foxhound is the recognition of blue-mottle as a correct colour for the breed". For hare-hunting however, the esteemed Beckford, regarded as the authority on packhounds in the late 18th century and early 19th century, favoured a cross "between the large, slow-hunting Harrier and the little Fox Beagle". Rawdon Lee, in his Modern Dogs, Sporting Division: Vol I of 1897, wrote that: "Unless some very considerable change takes place, it is extremely likely that the harrier will not survive very many generations, at any rate in this country." He referred to a smooth-coated Welsh Harrier, black or black and tan in colour, and, separately to a range of shoulder height in the breed from 15½ to 22 inches.

Struggle for Identity

Against that background, it is easy to see why this breed has struggled to maintain its identity over two centuries yet emerged with distinction. In his Hounds of 1913, Frank Townend Barton writes on Harriers that "there are about eighty-five packs in England and Wales, forty packs in Ireland, but only one in Scotland...one of the oldest packs of Harriers is the Pennistone...consisting of thirteen couples of 22 to 24 inch pure Harriers, or hounds of the English type". He stated that the Holcombe Harriers, 200 years old, was composed of twenty couples of 22 inch 'Old English Harriers'. I believe there are just over a dozen packs of Harrier still in existence, and, whilst a big reduction from the 85 of a century ago, the breed has survived rather better than Rawdon Lee's gloomy prediction.

But if the breed is to be recognised as such away from the hunting field, what should it look like? Should it resemble the Southern Hound with ears like the Sabueso Espanol and the Swiss Laufhund breeds? Should it be black and tan like the Welsh Harrier of old and the Schillerstovare, the Slovene Mountain Hound and the Kerry Beagles of the Scarteen pack? Should it be blue-mottled like the Hailsham Harriers or lemon and mainly white like the Istrian Hound and our own West Country Harrier? The Old English Harrier was cloddier than say our Studbook Harrier of today; but is that the right template? Is the

Harrier a 16 inch high hound or one standing at 22 inches?

Correct Phenotype

Devon and Sussex used to be strongholds of the Southern Hound blood, but there was once a harrier pack in Devon, hunted by a Mr Webber, and predecessors of the Silverton Harriers, which was slate-grey, rather like the Steinbracke of Germany. The wide diversity of view over the correct phenotype for the Harrier led to the Association of Masters of Harriers and Beagles to examine this in 1891 by way of a committee report. This committee found that there were at least a dozen different kinds of hare-hounds, quite diverse in type, with half their owners claiming theirs to be 'pure Harriers'. The committee recommended that all Harriers should be admitted to the Studbook, and then the book be closed. This led to a division between Studbook and Pure Harriers which continued to arouse great debate.

The Pure Harriers, like the Holcombe in Lancashire, were said to have better scenting skill; the Studbook Harriers to have too much drive. What is quite clear from this debate however, is that the aim was to breed a hunting dog to suit the country being hunted by that pack. What is the point of uniformity if a longer-legged hound is required in open country and a slower better scenting hound in very close country? In The Kennel Gazette of May 1884, there is a description of Harding Cox's Harriers running for seven hours seven minutes over a course of forty-eight miles. The hounds on this occasion were described as simply racing along and that "it took some pretty fast galloping to live with them." There are a number of salient points arising from this account.

Firstly, when breeders of sporting dogs are arguing about the correct shoulder height for their breed, the crucial question should always be asked: what terrain were they designed to work over? Secondly, the physique displayed by sporting breeds is rooted in field prowess and anyone tinkering with a breed standard needs watching. Sporting breeds like the Harrier developed in a hard school in which failure was not tolerated. For breeds that for centuries excelled in the hunting field to appear in the show ring featuring upright shoulders, under-muscled hindquarters or weak feet is a betrayal of the worst kind. What really is the point of fancying a particular breed if you then set out to sabotage its heritage?

Pursuit of Field Performance

The wide range of colours that once featured in the Harrier appeals to me. Harrier experts in the 19th century considered the blue-mottled or blue-pied hounds the 'true harrier type' but Foxhound blood has introduced the tricolours. The other colours favoured in the last century include hare-pied, badger-pied, lemon-pied, slate-grey or mainly white, especially in the West Country. Old English Red, as it was called, was a famous hound colour in the West, with black and tan favoured in Ireland. The Scarteen pack of Kerry Beagles, perpetuated by the remarkable Ryan family over three centuries, are handsome hounds, with admirers the world over. Few hound breeders breed on colour alone but favoured a jacket that produced a uniform pack. Hound breeders are seeking performance not a mindless observation of the wording of a breed's word picture or standard, so often sadly the case in KC show rings. If an outcross is needed the system permits this, in the packs: a Stud book Harrier dog mated to a Foxhound bitch is listed as ‘Appendix’ then when the resultant bitches are bred back to a Studbook Harrier dog, their offspring are then eligible for the Studbook as Harriers; the stallion must be a Harrier, not the other way around.

Cross-breeding in the constant search for field performance has given us so many distinguished pedigree breeds. The Harrier has been used successfully, i.e. Colonel Morrison's use of the Studbook Harrier Dunston Gangway to improve the Basset Hound's conformation, as an outcross. A world in which the closed gene pool is adhered to, no matter how diseased the progeny, how short-lived the dogs and no matter how exaggerations exaggerate themselves to the distress of the dog has little appeal for me. I'm not content either to see the ancient Harrier of England lost to us through a change in the law, now that hunting with dogs is legally regulated. Now is the time to conserve such a distinctive and well-bred hound; it is very much part of our national sporting heritage. We should benefit from the past not lightly discard it.

For me the Harrier is the perfect hound, handsome and with no exaggeration, representing all that is best in British hound breeding. The Cambridgeshire Harriers of Betty Gingell a few decades back, especially her Harkaway and her Housemaid, represented, for me, near-perfection in hound conformation. We have every reason to be proud of our Harrier. It is immensely cheering to learn of the new young huntsman at the Waveney Harriers, with country in East Suffolk/Norfolk, Joe Tesseyman, aged just 22, schooled at the Cottesmore and before that at the Badsworth and Bramham Moor, with great enthusiasm for his 22 couple pack, supported mainly by amateur whippers-in. If a small pack like this can be backed with such commitment and energy then the future of these excellent hounds is in good hands.