780 THE CHANGING FORTUNES OF GUNDOGS

THE CHANGING FORTUNES OF GUNDOGS

by David Hancock

“The main body of this family is composed of Spaniels proper, the Setters and Retrievers, while pointing dogs and diminutive allies are the miscellaneous members of the group. Head characteristics are rather broad skulls which are convex or ‘domed’ across the top, well-defined stop, fairly thick, long and pendant ears, loose lips, and rather full round eyes. Body formation is generally lithe and muscular, with the back slightly sloping to the set-on, legs of substantial but not coarse bone, and feet fairly large with toes that are capable of spreading out on soft earth. Tails are naturally long (except in some foreign Pointers which are purposely docked, and most British Spaniels), tapering and flagged with long fine hair on the underside. Coats are always soft, usually medium in length and well feathered. Employment is usually in flushing, setting, pointing and retrieving game.”

Dogs in Britain, Clifford LB Hubbard, Macmillan and Co., 1948.

Native Breeds Admired

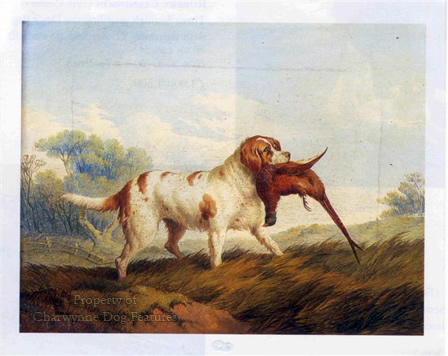

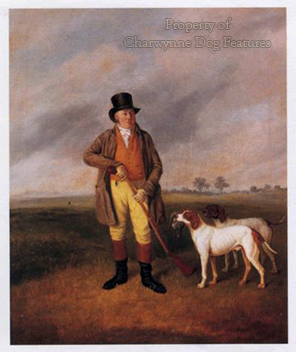

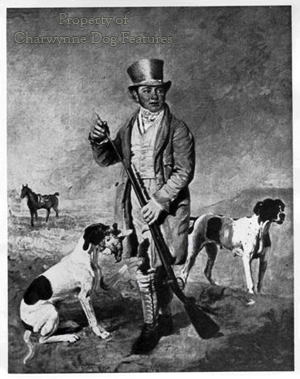

Britain has every reason to be proud of her contribution to the breeds of gundog in the world. Our sportsmen, supported by the landed families, developed the renowned breeds that are still active in the field today – pointers, setters and spaniels – although some of these breeds sadly are little used in the shooting field. If you want sheer style on the grouse moor, a dog that excels at flushing, starting or springing game, or a specialist retriever for picking up, our sporting breeds are still supreme. But if you want a dog that is capable of hunting game, pointing out where it is and then retrieving it to hand when it is shot, then you must choose a breed from overseas. In a later chapter I suggest that this should be rectified – that we in Britain should develop our own ‘hunt-point-retrieve’ breed. It is strange that British gundog breeders, revered the world over, have not responded to the contemporary demand for all-round skills in a gundog. As the paintings of George Morland, James Barenger and Ben Marshall illustrate, our Pointers once used to retrieve, as did some setters, as the Paul Jones painting of 1859 shows. Dog breeders are not usually so slow to respond to the market place, as our exports of gundogs in past centuries demonstrate.

Popularity has its Price

This book is a tribute to the gundog, whether a bird-dog, a water-dog, a decoy-dog, a flushing dog, a retrieving dog or a versatile all-rounder. Modern living presents many problems to sporting dogs, ranging from contemporary lifestyles that do not suit such active creatures to unwise unskilled breeding, often in the unashamed pursuit of money. But for some breeds, especially some gundog breeds, there is a special danger from their being appreciated, wanted, coveted and therefore over-bred – their sheer popularity. The sport of shooting is thriving; it is vital that the hard-working dogs providing irreplaceable support in the field to this sport are well-served, not just by trainers and shots once mature, but by their breeders, breed clubs and parent bodies. It would be good to see an energetic organisation like the British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) extending their remit still further in the promotion of healthier, better-bred and sounder gundogs, as well as the conservation of our native minor gundog breeds.

Challenge to British Breeds

If you look at the annual registrations of gundog breeds with the Kennel Club (KC), you can quickly see the fairly recent popularity nowadays of the hunt, point and retrieve (HPR) breeds from the continent. In the first decade of the 21st century, twice as many German Short-haired Pointers (GSPs) were registered here as our own native breed of Pointer; 1,000 more Hungarian Vizslas were registered than the combined totals of our Clumber, Field, Sussex and Irish Water Spaniels; more Weimaraners were registered than all our native setter breeds put together. More Italian Spinoni were registered than the combined totals of our Curly-coated Retrievers, Irish Red and White Setters and two of the minor spaniel breeds. Less than 50 years ago, only around 540 GSPs, 330 Weimaraners and under 100 Hungarian Vizslas were registered each year and no Spinoni. But nearly four times fewer Irish Setters were registered in 2000 as in 1975. Is this entirely down to sheer merit in the newly popular foreign breeds or an indication of our fondness for the exotic, the casual pursuit of novelty or copycat fashion-following?

Native Breed Decline

Even fifty years ago, the shooting men went for British gundogs; not any more. The preference for 'hunt, point and retrieve' breeds has largely caused this, but our national fascination with all things foreign plays a part too. The sustained popularity of the Labrador and Golden Retrievers and the English Springer and Cocker Spaniels mustn't be allowed to mask the worryingly small numbers of far too many of our native gundog breeds. In succeeding chapters I discuss this alarming decline in numbers of far too many of our long-established British breeds. There is also a regrettable fickleness in the fancying of gundog breeds. Taking the Gordon Setter as an example of this: in 1908, 27 were registered; in 1927, 74; in 1950, 100; in 1975, 255; in 1985, 586; in 2001, 288; in 2009, 192 and then 306 a year later. Such comparatively wide fluctuations in a small breeding population calls for extraordinary shrewdness from breeders if top quality dogs are to be bred and a virile gene pool maintained. Another of our native gundog breeds, the English Setter is declining alarmingly, with 240 being registered each year either side of the first World War, as many as 1,700 in 1980, a drop down to 768 in 2000, then further drops in 2009 (295) and 2011 (234). To lose 1,500 registrations in 30 years is a dramatic loss of patronage and of enormous concern to breed enthusiasts. This cannot be put down purely to changes in shooting habits.

Fashioning Fame

If you look at the list of the twenty most popular breeds of dog, as registered with the Kennel Club in 2011, you see a wide range of types. There are terrier and spaniel breeds, gundogs and herding dogs, foreign breeds and British ones, Toy dogs and working breeds. The Labrador Retriever easily heads the list, with nearly 40,000 registered, as in the previous four years. The Golden Retriever and the Cocker and English Springer Spaniels feature high in the popularity stakes, with all three breeds proving popular overseas too. The fashion-following of the dog-owning public can be seen in the changing fortunes of two British breeds: the Cocker Spaniel and the Fox Terrier. In 1910, over 600 Cockers and 1,500 wire-haired Fox Terriers were registered. The wire-haired Fox Terrier was top dog from 1920 to 1925 and again from 1928-1935. It was still the third most popular breed half a century ago. Eighty years ago it was the third most popular breed in the US too. Now less than 700 are registered here annually, only one third of the numbers registered in 1956.

The Cocker Spaniel was top dog here from 1936 to 1953, with over 7,000 registered each year in the 1950s. In the US in 1977, as many as 53,000 were registered, the breed having been top there even thirty years before. The registrations here of Cockers went up by 1,600 between 1989 and 1998, with the breed moving into third place here in 2000, with 13,000 registrations. Unlike the Fox Terrier, this is a story of sustained popularity. There seems no discernible reason for such varying fortunes. The Fox Terrier has lost its working role but perhaps the rise of the Jack Russell has contributed to its fall. The Cocker Spaniel is not worked as much as it once was, but the steady rise of another small spaniel breed - the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel has not affected its numbers. It is now more popular than the English Springer Spaniel.

Success Stories

The gundog breed success story of the 20th century here was undoubtedly that of the Labrador Retriever, with the Golden Retriever, the Cocker Spaniel and the English Springer not far behind. In his Dogs since 1900 of 1950, Arthur Croxton Smith wrote: "The year 1903 was memorable in the history of Labradors, which had hitherto been little known except among a few select sporting families...I must admit that before 1903 I had never seen one...Then in that year a class was provided for them at the Kennel Club show at the Crystal Palace." In 1908, 123 were registered, in 1912 - 281, in 1922 - 916, by the 1950s 4,000 were being registered each year, in the 1980s - 15,000 a year, rising to nearly 36,000 in 1998 and over 45,000 a year more recently. No other breed in the history of purebred dogs can match that rise in popularity. This degree of popularity calls for visionary breeding control, both a voluntary one at breeder level and firm leadership at the top, both at breed club and KC level. Sadly, this has not been entirely successful and far too many unsound unhealthy dogs have been born – and bred from, to respond to public demand. The breed and indeed the public deserve better and I argue for that in succeeding pages.

Threat from Abroad

Is there a need to restrict the often whimsical way in which fresh foreign breeds are imported into this country? Coming along behind the German short- and wire-haired pointers are the Stichelhaars and the Langhaars; behind the Large Munsterlander is the small variety and then there are the French Braques and Epagneuls, as well as the Dutch dogs: the Stabyhoun (Frisian Pointing Dog) and the Drentse Patrijshond, with the Italian Spinone and Bracco, the Portuguese Pointer and the Slovakian Rough-haired Pointer already imported. I am full of admiration for these breeds and have seen many of them at work in their native countries. I’d like to see talented well-bred specimens from those breeds gracing our shooting fields but I wouldn't want them to gain ground here at the expense of our own breeds. As I argue in Chapter 3, we are more than capable of creating our own ‘hunt-point-retrieve’ breed from native working stock.

Threats from Within

One of the less satisfactory aspects of the purebred dog industry in breeds that still work is the tiny contribution to the gene pool from the top working dogs. In the retriever world, the early dogs nearly always had field trial champions in their five-generation pedigree. Nowadays with over 50,000 retrievers being newly registered with the Kennel Club each year only a very small percentage have that input. Gundog experts who take the view that if the top working dogs are good then there is little wrong with the breed are not living in the real world. It is illuminating too to note that the only group of sporting dogs still earning their keep in the field and whose breeders still register their stock with the KC is the gundog group. Racing Greyhounds, hounds of the pack and working terriers do not feature in KC lists. Working sheepdogs never have. This is discussed in the

Changing Fortunes

Generally speaking, in the world of dogs, kennel clubs keep the breeds going and sportsmen keep the functions alive. Our Kennel Club does stage field trials, working tests, agility and obedience events but it's sportsmen who use hounds, gundogs and terriers as sporting assistants. The KC oversees the world of the pedigree gundog; in every decade, in the world of the show gundog, the faddists are at work, sadly in far too many breeds. Sporting dogs, like the setters, were once famed for their lung-power; now they are mostly slab-sided in the chest, despite the evidence that such a structure enhances the likelihood of bloat. A Cocker Spaniel can, it appears win Best-in-Show at Crufts with ears that defy the breed standard. ‘Oh, doesn't he know’, I can hear the gundog gurus proclaim, ‘that there is a division now between working and show gundogs?’ My response is two-fold: firstly nearly all the gundogs taking part in the working tests I have judged were show-bred; secondly I am prepared to bet that many readers of sporting magazines buy their gundog from a show breeder. In later pages, I make regular reference to the views of show ring judges; this is usually overlooked in books on dogs but here provides extremely valuable insight into the state of each gundog breed and is of value to the future breeding of each breed. I have also made full use of registration figures to illustrate the changing fortunes of each breed; popularity does not bring security to a breed, a lack of it can spell disaster for limited gene pools.

Fads may be passing indulgences for fanciers but they so often do lasting harm to breeds. If they did harm to the breeders who inflict them, rather than to the wretched dogs that suffer them, fads would be more tolerable and certainly more short-lived. But what are the comments of veterinary surgeons treating the ill-effects of misguided fads? In his informative book The Dog: Structure and Movement, published in 1970, RH Smythe, himself a vet, wrote: "...many of the people who keep, breed and exhibit dogs, have little knowledge of their basic anatomy or of the structural features underlying the physical formation insisted upon in the standards laid down for any particular breed. Nor do many of them - and this includes some of the accepted judges - know, when they handle a dog in or outside the show ring, the nature of the structures which give rise to the varying contours of the body, or why certain types of conformation are desirable and others harmful." Every gundog owner needs to know what his dog is for! This is covered in later chapters.

Celebratory Survey

I have striven in this book to promote the best long-term interests of gundogs, a book intended to be a celebratory survey of the gundog breeds, covering their origin, evolution, employment, essential form and their future. It is not a manual covering animal husbandry, training and breeding. It aims at the production of better gundogs in the years to come, with a renewed respect for their needs and best interests. Gundogs represent a very special collection of breeds both native and imported; they were developed by skilled breeders for a precise sporting function. It is our duty to continue the inspired work of those pioneers in each breed who bequeathed these precious breeds into our care. These words are intended to encourage just that.

“The discovery of the gun superseding the use of the falcon, the powers of the Dog were directed to the new acquisition; but his fleetness, wildness and courage, in quest of game, rendering him difficult to manage, a more useful kind was established, with shorter limbs and less speed…”

Sydenham Edwards in his Cynographica Britannica of 1800.

“There was great competition amongst English sportsmen at the beginning of the nineteenth century to secure the ideal gundog. There were plenty of breeds to choose from because gundogs had appeared long before the gun in England. Springers had flushed game for the falconer. ‘Crouchers’ had driven partridges or quails into a net and setters had been developed for the same purpose.”

Carson I A Ritchie in his The British Dog, Robert Hale, 1981.