779 AMERICAN BULLDOGS

THE BULLDOGS OF THE AMERICAS

by David Hancock

In North America most European breeds of dog have found their way to Canada and the United States. The American-made breed of Boston Terrier came originally from a Bulldog cross. In his book on the American Pit Bull Terrier of 1997, Louis Colby lists family after family which emigrated from Ireland, England and Wales, with their Bulldogs and Bull Terriers. In Canada, Lolly Wilkinson is still breeding her 'Original English Bulldogges' from stock originally taken to a remote area of Nova Scotia by English immigrants. The early colonists and settlers in North America needed stock dogs and hunting dogs, with cattle-pinning dogs becoming an urgent requirement. Perhaps predictably, the American stockmen took the English Bulldogs being imported and developed them into the American Bulldog, a bigger, usually more active and certainly less placid breed.

In North America most European breeds of dog have found their way to Canada and the United States. The American-made breed of Boston Terrier came originally from a Bulldog cross. In his book on the American Pit Bull Terrier of 1997, Louis Colby lists family after family which emigrated from Ireland, England and Wales, with their Bulldogs and Bull Terriers. In Canada, Lolly Wilkinson is still breeding her 'Original English Bulldogges' from stock originally taken to a remote area of Nova Scotia by English immigrants. The early colonists and settlers in North America needed stock dogs and hunting dogs, with cattle-pinning dogs becoming an urgent requirement. Perhaps predictably, the American stockmen took the English Bulldogs being imported and developed them into the American Bulldog, a bigger, usually more active and certainly less placid breed.

Variants of the Bulldog are bred in many places in the United States, with names like the Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog, which is now a stabilised type, the Georgia Bulldog, very much like a more powerful 18th century English Bulldog, Old Country Bulldogs and Old English Whites. But the most numerous and the best known are called simply American Bulldogs. One of the best known breeders of such dogs has been John D. Johnson of Summerville, Georgia, who believes the original stock came from an English settlement at Savannah in Georgia in 1733. He breeds huge, powerful but active dogs weighing over 100lbs. He started his kennel in the early 1950s, buying the best dogs he could from 'bulldog country' like Calhoun, Georgia, Big Sand Mountain in Alabama and Lookout Mountain in Tennessee.

John Blackwell of Collinsville, Oklahoma, one-time President of The American Bulldog Club of America, told me that the breed is free from the physical and mental weaknesses of so many purebred dogs registered with the American Kennel club and require no training as guard-dogs. Other early breeders of note were Alan Scott, Jack Tate, WC Bailey, Cell Ashley and Louie Hegwood. Respected breeders of the last twenty years or so include Tim Phaneuf, Mike MacDonald and David Farnetti. Sadly, after their influence for good, breeding standards have not been so high, with unwise and needless outcrosses to Pit Bull Terriers and Bullmastiffs, an absurd pursuit of huge dogs at the expense of soundness and an obsession with protection training in a type of dog which shouldn't require it.

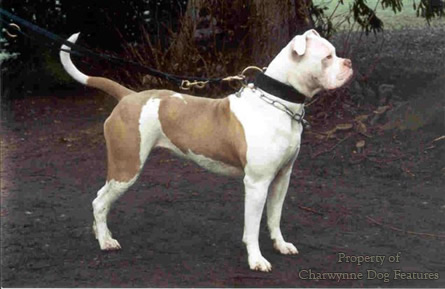

American breeders are prone to rate gigantic specimens in this breed, as if size itself had virtue. Closer acquaintance with the Mastiff breed in England would soon convince them of the folly of this approach. The American Bulldog comes in a variety of colours, but white or mostly white is the most common. Brindle and fawn dogs are not uncommon but usually feature plenty of white. Dogs can range in weight from 85 to 135lbs, bitches from 70 to around 100lbs. The smaller specimens have a distinct American Pit Bull Terrier look to them, which is hardly surprising for their blood was used in the creation of the latter breed. Bill Hines of Harlingen, Texas, has used his American Bulldogs as hog-dogs, in the classic medieval catch-dog manner, with all his stock being from old working lines.

If you lined up an American Bulldog with a solid brindle coat with a brindle Bullmastiff, few would argue against a common origin. In the United States, Tonia and Jon Lorensen, from their Templar Kennels, Litchfield, CT, have produced some admirable brindle American Bulldogs. They have their stock thoroughly health-checked and breed dogs both mentally and structurally sound. It is vital for such heavy dogs to be hip scored and for such powerful dogs to be bred with stable temperaments. The Templar Kennels set an excellent example in this respect. If British breeders of Bullmastiffs consider it necessary to widen their gene pool in the future, then the brindles at the Lorensen's kennels will be worth a glance.

In past millennia, the modified brachycephalic types of dog gave remarkable service to man as he explored the world. In Puerto Rico, the mastiff breed of Gran Mastino de Borinquen has been saved after years of neglect. The colonialisation which brought mastiff-like dogs to the Americas included many countries which do not have a recognised mastiff breed today. The Spanish and Portuguese, with their Filas, in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, explored a wide range of coastlines in the Americas, from California, Mexico and Florida to the north, Cuba, Panama and Central America in the middle, to Colombia, Equador, Peru and Chile on the western coast and Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina on the eastern coast of South America.

In Uruguay, the Perro Cimarron (otherwise known as the Perro Criollo or Perro Gaucho), a fawn or brindle 40kg dog about 60cms at the withers, is used as a watchdog, guard dog and boar catch-dog. Little known outside Uruguay, it is in fact now the national breed, with FCI recognition being sought. Cimarrones are agile, active, muscular dogs, with great determination in the chase. They are used in boar-hunting with a number of other breeds like the Dogo Argentino (banned in Britain under the DDA), exactly as medieval hunters used running mastiffs with hunting mastiffs or catch-dogs/holding dogs. This resuscitated breed bears the classic phenotype of the ancient hunting mastiffs.

In Puerto Rico, a Spanish colony until ceded to the United States in 1898, the Gran Mastino de Borinquen, a Bullmastiff-like breed, has been revived by Professor Hector De La Cruz Romero. Also known as the Puerto Rican Sporting Mastiff, Viejo Perro de Lydia Espanol and Gran Sato Bravo de los Campos (Barsino de Borinquen)/Perro Jibaro, those who can remember the breed from the turn of the century refer to them as the Old Perros Bravos. Some link the high incidence of rear dew claws in the breed to the old Spanish fighting breeds of mastiff type. Fanciers like Pura Cabassa, Modesto Maldonado, Edgardo Pauneto, Dr Gallardo and Anibal Torres have done much to develop this emergent mastiff breed. Ranging in height from 24" to 28" for males, 22" to 26" for females, weighing around 80lbs if from the fighting strain or up to 150lbs if from the boar catching strain, the coat colours are black, red, chestnut, buckskin or any of these brindled. It is good to hear of the progress of this mastiff breed. There may well be others in Central and South America awaiting discovery.

Those involved in the training of protection dogs will tell you how hard it is to find a dog that will actually attack a human being. It is thankfully rare to find a dog that will kill another dog, without being carefully bred and incited to do so. The mastiff breeds of today are famous for their relaxed attitude towards children, and quite remarkable tolerance of them, their stable temperament, faithfulness with their own family, natural instinctive guarding qualities and steadfastness when provoked. As guard dogs they rarely bark and seem to have an innate ability to distinguish between acceptable visitors and unwelcome intruders. For dogs with their violent past to emerge with such tolerance, trust and restraint is a telling commentary on their inherent qualities.

(there follows a critique written after judging the American Bulldog at a show, just over a decade ago)

AMERICAN & VICTORIAN BULLDOG CLASS CRITIQUE (as once judged by David Hancock)

General: An entry of a dozen American Bulldogs and one Victorian Bulldog produced a mixture of quality but a welcome consistency of active, lively, unexaggerated dogs and made an interesting contrast with a KC show ring for Bulldogs, where exaggeration amounting to deformity is the norm. The slippery surface made movement and the judging of it far from easy; the dogs were made to move slowly to give them the best chance of displaying soundness in these conditions. A larger outdoor ring would have permitted the extended trot that gives a judge a more valuable view of movement and so often reveals anatomical faults, especially a lack of coordination. Sound movement is much more vital in a large substantial dog, where excessive wear and tear on a heavy frame can be harmful to the dog. The pursuit of size for its own sake has ruined more than one KC- registered breed. For a 'catch-dog', agility, dash, power and sheer pound for pound physical strength will always be more important than height at the shoulder and great weight .

.

Forequarters: Heads were generally sound, with no massive skulls or dripping flews. A disproportionately large head is of no benefit to a Bulldog; too short a muzzle is a disaster. A breed expected to grip a dangerous adversary must be provided with a jaw that can seize and hold; this demands breadth and width. The KC-registered Bulldogs are practically muzzle-less and could never emulate their ancestors in the baiting ring. The muzzle should be at least one third of the skull length if function is to be honoured. Eyes were good, with no small, sunken ones or slightly bulging ones, two faults that easily appear in the bull-breeds. Fronts were good, the skill is to obtain width without the dog being 'out at elbow', a dreadful fault in show Bulldogs one hundred years ago. Fore legs were good with no over-boning, an undesirable feature in so many mastiff-type dogs. We are breeding active agile animals here not cart-horses. Feet were disappointing, just not tight enough. Elbows were encouraging, close fitting but not restricting forward reach. Shoulders were well placed, allowing free movement. Necks could have been more powerful, this feature is vital for a holding dog. In dogs of this type, the weight is on the forehand with the centre of gravity well forward. This means that, on the move, the dog prefers to carry its head relatively low; handlers should not impose a high head carriage on such a dog when demonstrating movement.

Torsos: It was good to see no 'dippy' backs or croups higher than the shoulders. This latter fault is seen in both the Fila Brasileiro and the Neapolitan Mastiff, with some fanciers of the latter claiming it as a breed characteristic! When the dog is higher at the croup than the shoulders, it has to walk with an unnatural rolling gait, which places great stress on the hips, and 'crabbing' on the move because the hindlegs are longer than the front ones. This is far too tiring for a dog requiring to be active. A more or less level topline provides the strength of body essential in a holding breed. Ribs were well sprung and reached well back. Loins were strong. I look for a hand's width between the leading edge of the dog's thigh and the last rib. More than that and the dog can have a weak loin; less than that and the dog is too cobby and will often lack stamina. I also look for three fingers width between the shoulder blades, to allow free movement in the charge, without ranginess.

Hindquarters: Most dogs had commendably free movement behind but lacked a power-packed first and second thigh. There is a lack of thigh muscle in far too many American Bulldogs and it is a fault needing to be bred out. Holding dogs must have immense drive from their hindquarters; the weight is already well forward and balance can only be achieved if the dog has a really hefty backside.

Temperament: This was admirable; any dog of this size and build not displaying sound temperament will disgrace the breed one day. Dogs of this size and strength must not be allowed to jump up at people in greeting, it is dangerous (and painful!) It was disappointing to witness owners permitting their dogs to bark at will. Holding dogs giving tongue are a menace in the hunting field and a nuisance in society. Such dogs were once praised for their silence in combat (Japanese Tosas still are). A powerful brave willing dog yapping like a village cur is not a good advertisement for any catch-dog breed.

Final comment: It was a privilege to have the opportunity of going over these splendid dogs and to meet their owners. Keep the flag flying for real dogs!