766 Picking Up Some French

PICKING UP SOME FRENCH

by David Hancock

The French gundog breeds, epagneuls, griffons and braques, are, despite the richly deserved admiration here for the Brittany, largely unknown to us but well worth a look. And, just as we failed to recognise our individual varieties of spaniel, like the Norfolk, the Devon and Welsh Cockers, the Tweed and the English Water Spaniels, despite utilising their blood in successor breeds, the French did the same with some of their ancient types. And perhaps that is the way it goes; we can’t conserve every variety – some being lost through a sheer lack of patronage or simply a lack of field prowess. But since so many contemporary gundog breeds have alarming inbreeding coefficients, and worrying rates of inherited defects, you could question the folly of permitting old breeds to fade away. The survival of domestic livestock breeds has demonstrated the wisdom of valuing long-established if not fashionable breeds. Visionaries like Joe Henson and his Rare Breeds Survival Trust provide lessons for dog breeders too.

The French gundog breeds, epagneuls, griffons and braques, are, despite the richly deserved admiration here for the Brittany, largely unknown to us but well worth a look. And, just as we failed to recognise our individual varieties of spaniel, like the Norfolk, the Devon and Welsh Cockers, the Tweed and the English Water Spaniels, despite utilising their blood in successor breeds, the French did the same with some of their ancient types. And perhaps that is the way it goes; we can’t conserve every variety – some being lost through a sheer lack of patronage or simply a lack of field prowess. But since so many contemporary gundog breeds have alarming inbreeding coefficients, and worrying rates of inherited defects, you could question the folly of permitting old breeds to fade away. The survival of domestic livestock breeds has demonstrated the wisdom of valuing long-established if not fashionable breeds. Visionaries like Joe Henson and his Rare Breeds Survival Trust provide lessons for dog breeders too.

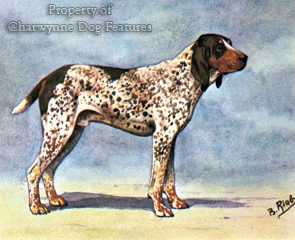

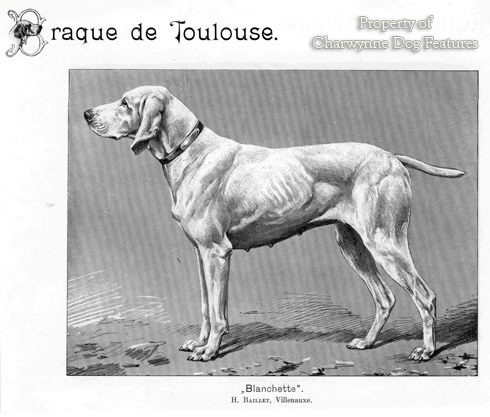

Even French gundog men have trouble remembering minor breeds or varieties such as the Epagneul de Saint-Usuge, the Epagneul du Larsac, the Braque de Toulouse, the Braque de Tarbes, the Gascony variety of the Braque Francais and the Griffon d’Arret Picard. They are of course big users of our gundog breeds. It is likely too that their native gundog breeds have received infusions of blood from ours in past centuries.

Only two French HPRs, the Brittany and the Korthals griffon, have so far made their mark outside France. Interest in the Braque du Bourbonnais here and in North America may be about to change that. After the Second World War only some 200 specimens of the breed existed, but now a well-planned resurgence is in place. An ancient breed from the very centre of France, its supporters claim that it has survived, without outcrosses, for nearly 500 years. Genetically, such minor breeds are very important, especially now that over breeding and unskilled breeding have left their mark on the highly-popular gundog breeds. An expensive but short-lived gundog is a poor investment both in training time and man-dog bonding terms.

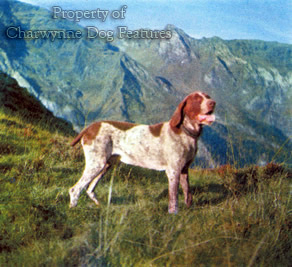

The Braque Francais, or French Pointer, is an ancient breed, according to the nationalistic French: "...undoubtedly the oldest breed of pointer in the world. It has been the origin of nearly all the continental and British ‘short-haired setters'." No concession to any Spanish origin there! The Auvergne Pointer comes from the old Pyrenean Braque and the Gascony Pointer. Drury, in his British Dogs of 1903, notes that the first pictorial record of the Pointer in Great Britain is the Tillemans painting of the Duke of Kingston with his kennel of Pointers in 1725. He commented that the latter were the "same elegant Franco-Italian type as the pointing dogs painted by Oudry and Desportes at the end of the 17th century."

Arkwright himself wrote that: "...the French were the chief admirers of the Italian braque...And after a time, though the heavier type of their own and the Navarrese braque still survived, it was quite eclipsed by the beautiful and racing-like Italian dogs with which Louis XIV and Louis XV filled their kennels." The French braques have come down from such stock. From Louis XIV onwards the French braques were envied all over Europe.

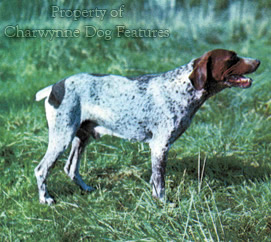

The French have quite a wide range of braques or pointing breeds: the Braque d'Auvergne (now introduced into the UK), the Braque Saint-Germain, the Braque de l'Ariege, the Braque du Bourbonnais, the Braque Dupuy - with few specimens remaining - as well as the Braque Francais in two sizes. They also have a good span of what we would call setters - their epagneul breeds: Breton, Francais, Picard, Pont-Audemer and Bleu de Picard. The Brittany is well established here and the Braque du Bourbonnais already introduced. The Bourbonnais Pointer is shown at Continental shows, with over 100 registered annually, after nearly disappearing in the 1960s-70s. Some are born tail-less or with just a rudimentary tail. A distinctive breed, with a very individual coat colour, roan with a pattern described either 'dressed like a trout' or 'lie de vin' (dregs of wine). I have heard this breed described as a short-haired Brittany in North America but my French colleagues dispute this. It is good to know that such a distinctive sporting breed has been saved. Sadly the Braque Charles X has been lost, perhaps subsumed into the other braque breeds.

We are learning to value the excellent Korthals Griffon, developed by a Dutchman in Germany but now registered as a French breed, but know little of another griffon variety named after its creator, the Boulet Griffon, developed using even more of the Barbet, in France. Emmanuel Boulet, a northern French industrialist, was advised by the great sporting authority of that time, Leon Vernier, and after ten years of experimental crosses, produced two particularly talented gundogs, Marco and Myra, behind every soft-coated griffon of that name. This soft-coat comes from the waterdog blood of the Barbet, possibly the original waterdog of Europe. Boulet sought the ‘dead-leaf’ colour in the coat of his breed, to blend with the vegetation of his favourite shooting ground, the forests of Londe. A number of French breeds have the imprint of their first advocate on them.

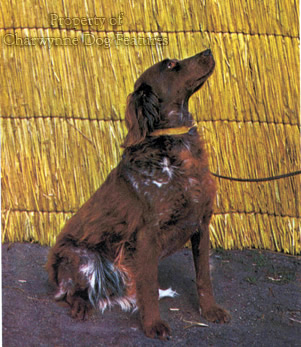

TheseFrench breeds are both distinctive and individual and should neverdisplay the 'type' shown in our setter breeds. One leading American expert on the breed has compared the Brittany to "a good riding cob, short-backed, full of fire and go, neither nervous nor high-strung, the epitome of stamina and carrying power for his size". And it is in America that the Brittany has made the greatest advance outside its native province, mainly as a field dog. The American Brittany club, formed as long ago as 1942, dropped the noun spaniel from its title, recognising that the misleading translation of epagneul as spaniel could bring misuse in the shooting field. (How I wish we ourselves would drop the noun spaniel from our Irish Water Spaniel breed-name, for it has and always will be a water retriever.)

But whether established in America or just becoming appreciated in the United Kingdom, the Brittany is essentially a working dog, they need the attention of one owner to develop best and regular field work to bring out their full personality and spirit. The story goes that the breed originated in the middle of the last century from a highly-talented hunting dog, born tailless, and so impressive in the field that visiting British sportsmen used him on their English, Irish and Gordon Setters, some of which remained in Brittany in the hands of local hunters. This is held to account for the range of colours found in the modern breed, although black is not acceptable in the United States. I am inclined to think that this range of colours existed in the setter-like gundogs on the continent well before the middle of the last century, as the contemporary epagneul breeds display in Holland and Germany, as well as France. But there is no doubt that these tailless setters hunted the wind in great style and made their name in their own way with sportsmen willing to try them. It always pays to be open-minded about breeds of dog, whether from here or afar.