765 The Real English Mastiff

REVIVING THE REAL ENGLISH MASTIFF

by David Hancock

by Ben Marshall.jpg) I do not believe that breeders of today have kept faith with the heritage behind the magnificent breeds handed down to them by those who used the breeds of Mastiff, Bullmastiff and Bulldog and designed them for that use. Any observer of giant badly-constructed Mastiffs and muzzle-less unathletic Bulldogs in our show rings cannot deny this. The Mastiff of the 18th century was more the size of the Bullmastiff. Dr J Sidney Turner, a well-known and respected Mastiff breeder of the 1890s, had only one of his top seven dogs exceeding 29 inches at the withers. Wynn, the acknowledged Mastiff expert of the 19th century, wrote: "Many good dogs are only 28 or 29 inches." The introduction of outside blood in any breed has long-lasting effects. When working and living in Germany on three separate occasions and researching the Great Dane, the German boarhound, there, it was apparent that boarhounds in the medieval hunt were around two feet at the shoulder. They were never bred for great size.

I do not believe that breeders of today have kept faith with the heritage behind the magnificent breeds handed down to them by those who used the breeds of Mastiff, Bullmastiff and Bulldog and designed them for that use. Any observer of giant badly-constructed Mastiffs and muzzle-less unathletic Bulldogs in our show rings cannot deny this. The Mastiff of the 18th century was more the size of the Bullmastiff. Dr J Sidney Turner, a well-known and respected Mastiff breeder of the 1890s, had only one of his top seven dogs exceeding 29 inches at the withers. Wynn, the acknowledged Mastiff expert of the 19th century, wrote: "Many good dogs are only 28 or 29 inches." The introduction of outside blood in any breed has long-lasting effects. When working and living in Germany on three separate occasions and researching the Great Dane, the German boarhound, there, it was apparent that boarhounds in the medieval hunt were around two feet at the shoulder. They were never bred for great size.

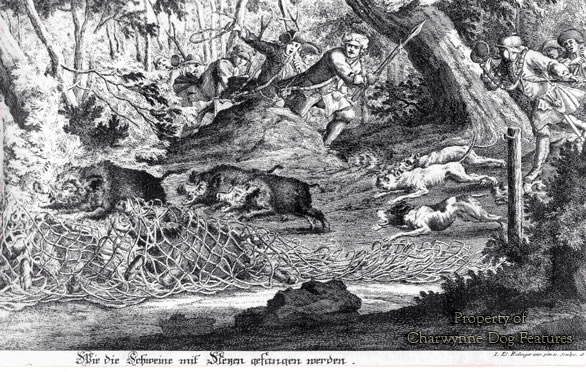

The great forests of central Europe once provided endless opportunities for hunting large quarry with dogs and in the 19th century this pursuit was conducted on a vast scale. In France there were over 350 packs of hounds. In 1890 the Czar of Russia organised a grand fourteen day hunt in which his party killed 42 European bison, 36 elk and 138 wild boar. In many of these hunts, scenthounds, sighthounds, running mastiffs or par force hounds (the true gazehounds) and hunting mastiffs (often held on the leash until needed at the kill and called 'bandogges' by the Saxons) were used in the same hunt. ‘Hunting cunning’ this was not!

The strong-headed broad-mouthed type of hunting mastiff was used all over medieval Europe in the pursuit of quarry such as elk, bison, boar, stag, bear and even aurochs. The surviving mastiff breeds range from those in England, France, Italy, Denmark and Germany to those developed in overseas possessions such as Brazil, Puerto Rico, the Canary Islands and South Africa. To be true to their heritage, these breeds need to be powerful but athletic, strongly-muscled yet still agile. Is our native breed, still not proudly claimed by the title - the English Mastiff, true to its heritage? It has a greater claim than the Bulldog to be a national emblem. Our canine heritage is part of our national culture and our native breeds represent the legacy of a considerable breeding achievement. In the world of dogs, our reputation as breeders is slipping and our reputation as exaggerators growing. I am all in favour of fanciers being able to import outstanding dogs from abroad; I am not in favour of our native breeds being not just neglected but bred carelessly to a 'new' design. One of our most famous native breeds now looks less and less like its distant ancestors and this breed, the Mastiff, should be treasured.

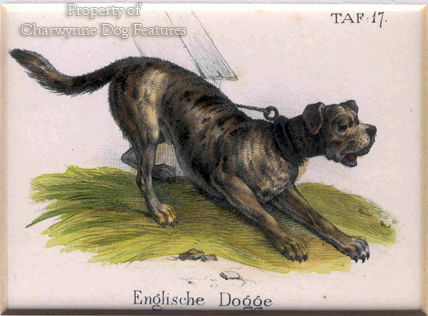

The lack of a modern function for this distinguished breed, allied to misguided show criteria and a closed gene pool, hasn't helped. Our Mastiff was once revered all over northern Europe as a hunting dog: the Englische Dogge. It was a powerful strong-headed active agile heavy hound, used to close with quarry and seize it for the accompanying hunters. It was not a giant sloth but a mighty canine athlete. In the nineteenth century, in a misplaced desire for great size and immense bulk, breeders blended Mastiff blood with that of imported dogs, such as Great Danes, Alpine Mastiffs and Tibetan Mastiffs, to create the giant breed we have with us today. As a direct result we are left with a very different Englische Dogge, more a fawn Alpine Mastiff, and shame on us for that.

In the Middle Ages, Northern European sportsmen favoured what they themselves called the Englische Dogge, a blend of mastiff and scenthound, often called staghounds in England at that time. As specialist hounds became favoured in Britain and much of our big game became extinct, these huge, strong-headed, tucked-up, hard-running hunting dogs stayed in fashion in Central Europe, to hunt bison, wild bull, boar and stag. Cox, writing in 1674, described how the King of Poland 'hath a great race of English Mastiffs' which 'are brought up to play upon greater Beasts.' In Germany there were strong-headed par force hounds known as hetzrude or saurude, which contributed to the development of the Deutsche Dogge or Great Dane. The Saxons and the Celts had their par force hounds, big, ferocious, strong-running, heavy-headed and recklessly-brave hunting dogs.

Heinrich Wilm Doebel, in his Huntsman Practica of the late 1700s, wrote of them: "Besides the English Doggen which are the largest there are the Baren and Bullenbeisser which...are much smaller...as the former sometimes stand three feet high." In 1836, Hartig was writing in his hunting lexicon that: "The stature of the English Dogge is beautiful, long and gracefully muscular. The stature of the Bullenbeisser is less pleasing. It is chunkier and the head is broad, dull and short. But these dogs are extremely courageous fearing no danger. Most of them are fawn with a black mask." There is a fair description of a prototypal mastiff-like 'catch-dog', leading to the development of our Bulldog type..

Against a background of the unrestricted movement of valuable dogs, it is possible to detect distinct forms of 'doggen', or mastiff-type dogs, in Northern Europe from the 14th to the 19th century. The word 'dogge', pronounced 'dogga', comes from the Old English word ‘docga’ – meaning the mastiff type; dogge is German for mastiff, dogg in Swedish, dogue in French, dogo in Spanish, and is used here to avoid confusion by using the word mastiff, nowadays used precisely as a breed name, to refer to a powerfully-built, short-haired, large-headed, drop-eared, strongly-muzzled heavy hound or hunting dog with immensely strong jaws and a willingness to attack and kill its quarry, rather than just chase it and then bay it. For continental hunters to prize our ‘Englische Dogge’ so highly is an immense compliment; they would not rate the contemporary English Mastiff, now bred for bulk not any distinct function.

When I see the Mastiff of my country in the show ring at World Dog Shows I could weep for the breed. When I see hybrid mastiffs at unofficial dog shows I am enormously encouraged; their breeders are seeking substantial but unexaggerated dogs, combining size, strength and soundness, not the slavish perpetuation of a breed ‘gone wrong’. The show ring has saved some pedigree breeds from extinction; but it has condemned a few to a shortened pain-filled existence, purely to satisfy a misguided human whim – the favouring of a dog breed because of its pedigree not its performance. The Englische Dogge was widely admired; the English Mastiff of today is pitied by any right-minded dog lover. This is a situation screaming out for action and it would not be that difficult to restore this breed to a more honest representation. On animal welfare grounds alone this once magnificent hunting mastiff urgently needs recasting, but where is the will to do so? Certainly not within the pedigree Mastiff breed fanciers, they seem curiously content with the massive inactive lump disgracing our national show rings. Shame on them!