751PERFECTING THE PUDELPOINTER

PERFECTING THE PUDELPOINTER

by David Hancock

Sportsmen have long striven to improve their gundogs and at times, especially in the late 19th century, each breed has benefited from such strivings. All sporting dogs whether they are hounds, terriers or gundogs have to suit the terrain over which they hunt, the quarry they pursue and the objects of the sport itself. When function was the only decider, form was easier to shape. Stamina, robustness and ability to perform their set task, backed by perseverance, decided the stock to be used as breeding material. Nearly all our revered gundog breeds came down to us as the direct result of the dedication of pioneer breeders. Some were gifted, some inspired, a few almost fanatical, in their pursuit of the perfect gundog for their needs.

Sportsmen have long striven to improve their gundogs and at times, especially in the late 19th century, each breed has benefited from such strivings. All sporting dogs whether they are hounds, terriers or gundogs have to suit the terrain over which they hunt, the quarry they pursue and the objects of the sport itself. When function was the only decider, form was easier to shape. Stamina, robustness and ability to perform their set task, backed by perseverance, decided the stock to be used as breeding material. Nearly all our revered gundog breeds came down to us as the direct result of the dedication of pioneer breeders. Some were gifted, some inspired, a few almost fanatical, in their pursuit of the perfect gundog for their needs.

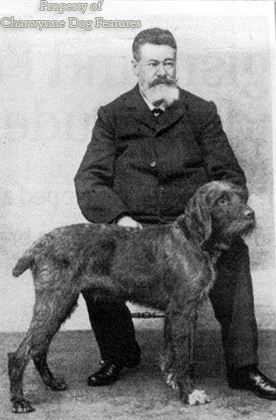

The contribution of Laverack and Llewellin to the setters, Arkwright to Pointers, Shirley to Flatcoats and Phillips to the spaniels is well documented. The remarkable dedicated pursuit of clearly identified qualities in an all-rounder led Korthals to bequeath us the Wire-haired Pointing Griffon that bears his name. But both the breed of Pudelpointer and its creator, despite having a long established history, is hardly known here. Sigismund Freiherr von Zedlitz-Neukirch is not a name to be forgotten quickly or, sadly, remembered easily, but in the second half of the 19th century he almost single-handedly created, from Pointer and Poodle stock, the breed of Pudelpointer. He is to this day remembered as perhaps the most important pioneer in German pointing dogs. It is surprising too that in Germany he chose to base his breeding plans on the Pointer from Britain and the Poodle, normally linked with France. But he knew what he wanted and where to get it.

Born to a noble family, a keen hunter and an innovator, von Zedlitz wished to preserve what he called ‘the real German working dog’. He set out the desired qualities as: having a good nose, great stamina, a griffon coat in a ‘forest’ colour, with sound temperament. He insisted that the dog should be highly proficient in water, be extremely biddable, be bold and curious, and, unusually, give tongue when working. Surprisingly, he did not consider that the German gundogs of that time, 1870-80, possess these qualities to his expectations, which would not have made him at all popular with his sporting peers. In an article published in 1881, he wrote what could loosely be translated as ‘We ought to try, utilising the bloodlines of the Pointer and the Poodle, to produce top-quality working dogs that will pass on to their offspring, strongly and consistently, these stated qualities. We are seeking a leggy, rough-coated, stylish but strongly-made pointing dog. It will not resemble a Poodle, but display its cleverness and common sense.’

For this breeding plan, he himself provided a black standard Poodle bitch and persuaded a royal forester called Walter to mate her to a substantially-built brown and white Pointer from the kennels of the Prince of Wales but owned by the future emperor of Germany, Friedrich III. Their first litter was born in 1881. Originally named by breed-type as Hegewald (von Zedlitz’s pen-name) Rauhbarten (rough beards), under the affix vom Wolfsdorf, their breeders were delighted with the results. Von Zedlitz admired the combination of the intelligence of the Poodle with the quartering, scent-seeking, stamina and obedience of the Pointer. The short harsh coat was weather-proof and its colour blended well with their hunting grounds. A further infusion of Pointer blood was used and gradually the vom Wolfsdorf dogs became more widely known. Less adventurous and more conventional German gundog men were outraged by such imaginative thinking - and irritated by its success!

The well-known German writer of that time, Richard Strebel, a man of some influence, led the opposition, declaring, in rough translation: ‘…this brings nothing new, the result is a dog resembling a German pointing dog, nothing else’, calling it a ‘stillborn child’. But von Zedlitz ignored the scorn and abuse, and like Korthals, used his writings to expose the limited thinking of the German gundog world at that time. Unabashed, von Zedlitz founded the Society for Testing Working Dogs in the Field in 1891 and a year later, the first working test for Pudelpointers took place. Two dogs from the new breed were successfully entered by their breeder Walter. The breed prospered and between 1894 and 1899, 120 dogs were placed on the breed register. By 1934, there were over 500 Pudelpointers, but occasionally, unwanted features such as a woolly black coat cropped up and had to be bred out.

The Second World War did the breed no favours but by 2000, there were around 180 Pudelpointer breeders in Germany, some exporting their stock to neighbouring countries and to North America. Two feet high, with a harsh weatherproof coat in a distinctive hue, they could from afar be seen to be either a Korthals or even a wire-haired German Pointer, but the Pudelpointer is preferred in a solid chestnut to dead-leaf coat-colour and when all three breeds are alongside each other, the separate breed identities soon manifest themselves. It’s worth a thought however on how the other German wire and stichel-haar breeds were first bred and from what ingredients. Sportsmen who have used all of these in the field have reported different styles of working but none have complained about the working performance of the Pudelpointer. When working in Germany, I heard it described as the perfect rough shooter’s dog: staunch and enduring, a gifted tracker, a fine retriever, especially from water, intelligent and easy to train, with a non-shedding coat. It was not considered a show dog but one brought up for the demands of fieldwork, not notably pet dog material; a dog looking for employment. I was pleased to learn that a Scottish sportsman has imported the breed and been highly impressed by them, in demanding terrain.

The sheer determination of an individual like von Zedlitz brings outstanding dogs into our use; his utter conviction was unusual and admirable. Who in late Victorian Britain would have had the will and the commitment to breed a totally new breed of gundog? In more enlightened times, we do come across deliberate gundog hybrids being favoured by quite experienced gundog men. How enterprising and how admirable the self-confidence to proceed with such a non-conformist approach. Sporting dogs must always be fit for purpose; casually-perpetuated pure-breeding can sometimes be the laziest of answers.