749 TOYING WITH TERRIERS

TOYING WITH TERRIERS

by David Hancock

.jpg) In so many ways the gap between the requirements of dog show breeders and sporting dog users is entirely predictable and a natural separation. Whilst there are some excellent dual-purpose gundogs, most exhibition gundogs are not bred for work. I see some well-constructed Whippets in the show ring, usually from certain kennels or lines but far too many show Whippets are just that – ornamental dogs. But it’s in the terrier world that I see the biggest gap between the working dogs and the show ones, with the occasional exception in the Parson Russell and Lakeland Terrier classes. It didn’t used to be like that, despite the Yorkshire Terrier being consigned to the Toy dog group. And it shouldn’t be like that, a sporting terrier should honour its title - wherever it appears.

In so many ways the gap between the requirements of dog show breeders and sporting dog users is entirely predictable and a natural separation. Whilst there are some excellent dual-purpose gundogs, most exhibition gundogs are not bred for work. I see some well-constructed Whippets in the show ring, usually from certain kennels or lines but far too many show Whippets are just that – ornamental dogs. But it’s in the terrier world that I see the biggest gap between the working dogs and the show ones, with the occasional exception in the Parson Russell and Lakeland Terrier classes. It didn’t used to be like that, despite the Yorkshire Terrier being consigned to the Toy dog group. And it shouldn’t be like that, a sporting terrier should honour its title - wherever it appears.

Many sporting terrier fanciers at the end of the 19th century and on into Edwardian times, from the Rev John Russell to Major Harding Cox, showed and worked their terriers. The pioneers in each breed of sporting terrier were quite often men who worked terriers and knew the requirements for the task. A century later and the separation between terriers that work and those that just pose is all too apparent and it’s not good for the terrier breeds. A devoted working terrier man like Sir Jocelyn Lucas acknowledged the differing needs and the different dogs the show ring was encouraging. In many terrier breeds the increasing separation was identified and regretted by the early breeders. They were rarely anti-show just pro-working construction in their dogs and often despaired of their fellow breeders, who so often put winning rosettes ahead of the best interests of their breed. Experts like Rosslyn Bruce in Fox Terriers, WL McCandlish in Scottish Terriers, Florence Ross in Cairn Terriers and, later, Walter Gardner in Border Terriers, saw the perils in breeding terriers that displayed features unwanted in a working dog. Each of them wrote valuable books on their breeds in a vain attempt to rectify this trend.

At the end of the 19th century and in stark contrast to today, the Kennel Club’s publication The Kennel Gazette, printed the most hard-hitting show critiques from knowledgeable judges who never hesitated to speak up for their breeds. Today that publication is a supine fawning glorification of show ring excess, contributing nothing to the betterment of breeds. I wrote for it for a decade before daring to write critically of the KC and being discarded. A self-regarding organisation like the Kennel Club needs dissenting voices more than most, if only to keep it honest. To see the effect of unregulated self-congratulatory showing, look at the Yorkshire Terrier of today, compared to the early specimens in this spirited little breed. Small black and tan working dogs have been known in Yorkshire for several centuries. The little Halifax Terrier and the Yorkshire Heeler were commonplace before the advent of breeding for ‘the pedigree’. The latter breed has been lost, unlike the neighbouring Lancashire Heeler, whilst the former is perpetuated in the Yorkshire Terrier, the tiny ornamental breed of that name, in the Kennel Club’s Toy group.

This modern show ‘terrier’ from Yorkshire is very much a manufactured breed, materialising around 1860. In time its devotees hijacked the breed name for the ornamental exhibitors’ type of seven pound dog and in due course, the Yorkshire Terrier Club was founded in 1898. It is not historically accurate for a long-coated dwarf dog with a coat of such silky texture, so tiny physically and displayed with its topknot beribboned to be dubbed the ‘Yorkshire Terrier’. Originally, this dog was bigger and more robust, with specimens weighing from 10 to 14lbs, but 6lbs has been the weight of most of the bigger exhibits for the last century; today we see a wee scrap of a dog with a suppressed terrier spirit in a highly ornamental container.

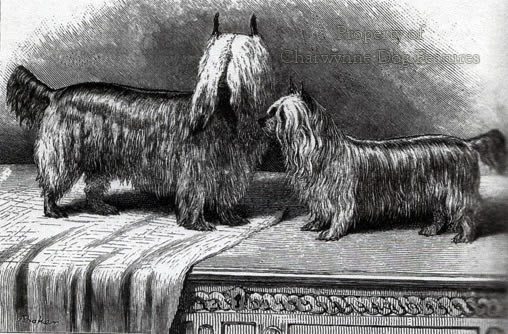

Now I have nothing against small companion dogs that bring comfort to so many older or lonely people. I have nothing but admiration for the Yorkie; a dog of that size needs all the support it can get! I do object however to the name Yorkshire Terrier being misapplied in this way. This is not the earth-dog of that great sporting county. Its origins lie in sporting terriers, mainly those from Scotland. The links between the Clydesdale, Paisley, Skye, Dandie Dinmont and the working terriers of Yorkshire are many. The Clydesdale was a soft-coated Skye Terrier, a bright steel blue colour with a clear golden tan on the head, legs and feet. At the Islington show of 1862, Scotch terriers under six pounds were exhibited and a year later, white, fawn and blue Scotch, under seven and over seven pounds were shown. Among the blues was Platt’s Mossy, no. 3628 in the Yorkshire Terrier stud book. In 1869, the famous Huddersfield Ben made his first appearance, being placed second as a Scotch Terrier. He subsequently sired many of the ‘Toy Terriers (rough and broken-haired)’ entries and is a founder of the modern breed of Yorkie. The great sporting county of Yorkshire surrendered its breed of working earth-dog to the show ring.

The Yorkie should be called just that and the title of terrier removed. Then the very capable breeders of Yorkshire’s working terriers could produce a true terrier bearing their county’s name. Preferably blue and tan, 12 to 14 inches at the withers, 12 to 14lbs in weight, with a harsh close ‘pin-wire’ coat, it could be a winner! What a challenge for an artisan breeder and what a reward for a true Yorkshireman! It would also demonstrate to the show fraternity that they may have created a gap between working and ornamental dogs, but that gap can be closed and the terriermen of Yorkshire could show them how. We may have lost the Cheshire Terrier and not persevered with a Devonshire Terrier as such, but the Norfolk was revived and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier became recognised. The Sporting Lucas is evolving and the Plummer in safe hands despite desires to get KC-recognition for the latter.

It is worth recalling the words of two famous working terriermen on this gap between show and field. Jocelyn Lucas, in his The New Book of the Sealyham, Simpkin Marshall Ltd., 1929, writes: “The greatest tragedy that can ever befall a breed is to become purely a fancier’s dog…breeders must aim not merely at producing a good-looking dog, but also a workman. The cloddy dog who gets tired after walking half a mile, and who is too slow to catch a rat is a danger to the breed.” He might well have added that it is better to have a dog bigger than a rat! And the renowned terrier fancier Arthur Blake Heinemann, in his words on Hunt Terriers in The Foxhound, October, 1912, stated: “To-day it is fashionable to hold classes for working terriers at Dog Shows, and specialize in various breeds or strains, each vying with the other for press-puffs and paragraphs, and capping each other’s fairy-tales as to their terrier’s exploits; for…this is a profitable game, and as one judge and breeder of the latest candidates for fashion’s favour said to me, ‘I know they’re no use except at home amongst themselves, but what would you do? I can sell them like hot cakes.’”

The Kennel Club-recognised breed of Yorkshire Terrier certainly sells like hotcakes; thirty years ago around 20,000 were being registered with the KC each year, there are still more being registered each year than the combined totals of fourteen of our sporting terrier breeds. It is easy to see what caused the gap between bench and field; real terriermen don’t breed their dogs for financial reward. Their reward comes from the pride in seeing what their progeny can do rather than what they look like. The great Irish Terrier breeder of one hundred years ago, William Graham, once cast his eye over a show entry of his time and declared: 'Some men show pedigrees; I show dogs and take the prizes.' A genuine Yorkshire Terrier would win - and work!