748 RECALLING THE SCOTTISH WHEATEN

RECALLING THE SCOTTISH WHEATEN

by David Hancock

“Scotland is prolific in Terriers, and for the most part these are long-backed and short-legged dogs. Such are the Dandie Dinmont, the Skye, and the Aberdeen Terriers, the last now merged in the class recognized at our shows as the Scottish, or Scotch, Terrier; but the old hard and short-haired “Terry” of the West of Scotland was much nearer in shape to a modern Fox-terrier, though with a shorter and rounder head, the colour of his hard, wiry coat mostly sandy, the face free from long hair, although some show a beard, and the small ears carried in most instances semi-erect, in some pricked.”

“Scotland is prolific in Terriers, and for the most part these are long-backed and short-legged dogs. Such are the Dandie Dinmont, the Skye, and the Aberdeen Terriers, the last now merged in the class recognized at our shows as the Scottish, or Scotch, Terrier; but the old hard and short-haired “Terry” of the West of Scotland was much nearer in shape to a modern Fox-terrier, though with a shorter and rounder head, the colour of his hard, wiry coat mostly sandy, the face free from long hair, although some show a beard, and the small ears carried in most instances semi-erect, in some pricked.”

From British Dogs by WD Drury, Upcott Gill, 1903.

Whatever happened to the ‘Terry’, the old hard-haired sandy-coloured working terrier of the West of Scotland? Did it live on in the wheaten Scottish Terrier, before that variety lost favour? Nowadays when regarding an entry of show ring Scotties you could be forgiven for thinking the breed was only black-coated, just as the Westie is white. It is relevant too to keep in mind that both these breeds were once far less heavily coated, their working man owners not wishing to devote hours to their coats, unlike the grooming fetishists of the modern show ring, especially in North America. A heavy coat on a working dog, whatever its function was never sought by pioneer breeders. Weatherproofing comes from the texture of the coat and the hair-density not its length.

The wheaten hue is a common terrier colouration, being found in the Border, Lakeland, Norfolk, Norwich, Cairn and Scottish Terrier breeds, as well as the terriers from Ireland. Morning Nip was the first wheaten champion in Scottish Terriers. He was said to have a lovely golden coat, flecked with black hairs; he had great presence in the ring and was very highly rated as a model for the breed. After a highly successful show career, he was bought by Dr Fayette Ewing and taken to the United States. In the early 1920s black became the ‘only’ colour in the breed, which made the selling of a puppy in any other shade extremely difficult. This followed the production from purebred stock of white Scotties, leading to allegations of sly outcrosses to Sealyhams. Such ignorance of the breed’s colour gene-pool led to the favouring of solid jet black jackets, despite the fact that the use of brindle blood was known to improve coat texture.

This concentration on the colour black has not brought with it consistent quality. Judges of the breed in 2010 reported: ‘There were some common failings; dogs deep in chest but not wide, or slightly lacking forechest, putting front legs at the end of the body instead of underneath, and there were many with loose elbows.’ And another: ‘I was disappointed with the overall quality. Many were overweight and in soft condition, lacking muscletone and general fitness. Movement generally was not very good and quite a few failed in front action, lacking reach.’ These are disturbing faults in a sporting terrier breed. The breed is not being helped by the almost reckless awarding of coveted prizes: in 2009, a judge had an entry of just three dogs but still went ahead and awarded both challenge certificates on offer! Talented Scottie breeders of old like McCandlish, in the breed’s early days, and Medcalf, half a century later, would not have approved, they relentlessly sought real quality. It is never enough just to turn up on the day.

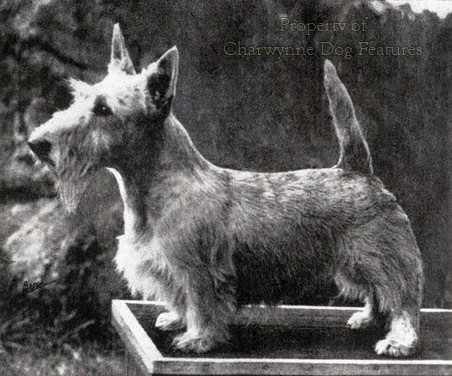

The Medwal kennel of Walter Medcalf became renowned for its wheaten Scotties from immediately before the Second World War to the 1950s. Medcalf likened this coat colour to a lightly baked loaf of bread; others compared it to a field of ripe corn. He found this coat colour provided the best waterproofing, thought that the blacks were usually too soft-coated but also admired the brindles. The Medwal dogs always had excellent pigmentation as well as extremely handsome coats. Every wheaten Scottie bred here goes back to his line. Not many wheaten Scotties are seen on the show benches today. I believe the last wheaten champion was Glenecker Golden Girl in 1966. The first published standard for the breed didn’t include the wheaten shade but the 1885 one laid down the breed’s colour range as: steel or iron-grey, brindled or grizzled, black, sandy and wheaten. Walter Medcalf’s daughter Mrs GB Willatt tells me that her father always encouraged his dogs to rat and introduced pups early to their traditional foe. His outstanding bitch Medwal Miss Mustard produced a litter of five champions. Walter’s father George Medcalf was a distinguished breeder of Fox Terriers, both wires and smooths, selling winning stock to the Duchess of Newcastle and to success on the Continent; a fine terrier dynasty.

Sandy-wheaten, silver-grey and grey-wheaten can be confused, but the real wheaten coat is truly golden and very attractive. In his book The Inheritance of Coat Colour in Dogs, of 1979, Clarence C Little writes: ‘Light-yellow or cream and pure-white Scotties (formerly known as Roseneath Terriers) represent a wheaten type in which the gene for full pigmentation has been replaced by the paling gene…Wheatens, like sables in other breeds, may be clear-colored or may show varying amounts of scattered dark pigment, especially on the back and sides. Usually this disappears with age.’ In a number of terrier breeds the pups can be much darker than their parents but lighten gradually to their final colour. Choosing a pup on a preferred shade of coat needs more knowledge than most pet owners possess. Adulthood can bring change.

Pet owners would however warm to the words of perhaps the greatest expert on Scotties, WL McCandlish, who wrote, in his book on the breed of nearly a century ago: ‘The first aim of a breeder should be to produce the dog best fitted to be the companion of man in and out of doors…I should like to shoot all breeders of Scottish Terriers who breed dogs to suit judges, those who tell you, for instance, that you must breed for straight fronts and short backs, because such judges insist on these two catch-penny phrases, even though they are fully aware that to obtain these two subsidiary features they must ignore expression and intelligence, type of body, and true activity.’ A visitor to his kennel in 1905 reported her amazement at seeing 30 to 40 Scotties that all looked completely uniform in appearance. Before the First World War, his was the leading kennel, bringing balance, great quality heads and ears, bigger quarters with muscular thighs, tails with a good strong root, and a symmetrical build without losing workmanlike attributes too, some feat. McCandlish favoured an 18lb dog, nowadays the standard asks for a 19-23lb dog. In his day steel or iron grey coats were listed, today they are not; sandy was then an accepted coat colour, today it is not listed.

Writing in his The Dogs of Scotland of 1891, Thomson Gray, the great authority on dogs there before the show ring took them over, stated: ‘The usual colour of the old Scottish Terrier was sandy. No other word is so expressive of the colour, and will readily be understood by all Scotsmen. There were other colours, such as grizzle and brindle, but “sandy” was the popular one. They were not bred for ‘fancy’ but for work, consequently the carriage of ears, and other little ‘points of beauty’ so greatly insisted upon by ‘fanciers’, were ignored, and only the sterling qualities of the animal prized. If he could kill rats, draw a badger, and face a cat without flinching, he was termed a terrier; if not, he was a “guid-for-naething useless brute…’ He was probably describing what others have called the ‘terry’, leggier and hard-coated; he would have been more than surprised to find the Scottish Terrier of today forever in black.