735 THE HIMALAYAN SIGHTHOUND

THE HIMALAYAN SIGHTHOUND

by David Hancock

If the Saluki is the canine aristocrat of the desert, then surely the Afghan Hound is the canine aristocrat of the mountains. Those mountains determined the coat of the Afghan Hound, unique amongst sighthounds for that longer thicker jacket. I have read of this breed being developed in isolation because of the location of its homeland. This is contradicted by the perpetual invasions; Afghanistan, like Poland, is one of those ‘cross-road’ countries, where invaders are either entering from the west or east or coming in from the south and north too. The Arabs brought their Salukis, the Tajiks their Tazis and, no doubt, Alexander the Great some Greek hunting dogs. More primitive dogs resemble each other; when restricted to pure-breeding, they unsurprisingly take on the exaggerations that define them. The Afghan Hound has emerged as a very distinctive breed but this has, sadly but inevitably, led to its coat being prized ahead of its sighthound capabilities.

If the Saluki is the canine aristocrat of the desert, then surely the Afghan Hound is the canine aristocrat of the mountains. Those mountains determined the coat of the Afghan Hound, unique amongst sighthounds for that longer thicker jacket. I have read of this breed being developed in isolation because of the location of its homeland. This is contradicted by the perpetual invasions; Afghanistan, like Poland, is one of those ‘cross-road’ countries, where invaders are either entering from the west or east or coming in from the south and north too. The Arabs brought their Salukis, the Tajiks their Tazis and, no doubt, Alexander the Great some Greek hunting dogs. More primitive dogs resemble each other; when restricted to pure-breeding, they unsurprisingly take on the exaggerations that define them. The Afghan Hound has emerged as a very distinctive breed but this has, sadly but inevitably, led to its coat being prized ahead of its sighthound capabilities.

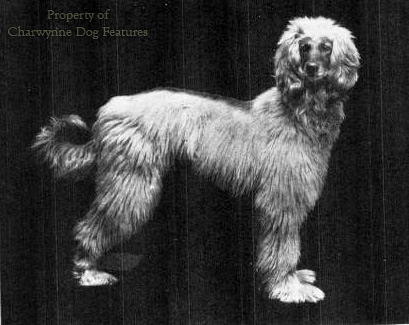

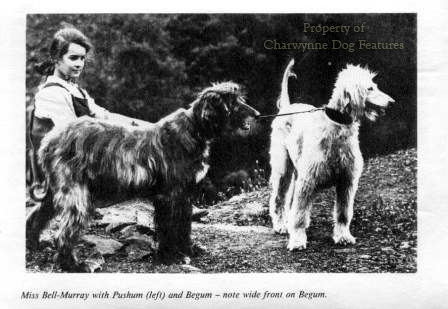

As with all such breeds, a different type, slightly heavier-boned and more coated, evolved in the mountains, with the plains variety developing as lighter-framed and less coated. Major and Mrs Amps imported the former, the Ghaznis, Major and Mrs Bell-Murray the latter. Half a century ago, Gulbaz, writing in Kabul, recorded: “The greyhound or ‘Tazi’ as it is called all over Afghanistan…There are three popular breeds of this dog. One is called ‘Bakhmull’ meaning velvet because it has a long silky coat which covers the whole body including the ears. Another is called ‘Luchak’ or smooth-coated, and the third one is ‘Kalagh’ (rhyming with ‘blast’) which has long silky hairs on its ears and legs, but the rest of the body is smooth-coated.” This Saluki-like Afghan Hound shows that hunters need dogs to suit quarry, climate and country and have little time for the luxury of breed points or cosmetic whim.

I give our Afghan enthusiasts many plaudits for staging race meetings for their hounds. In a recent report on an Afghan Hound race meeting at Ellesmere Port, these words were used in the introduction: “Those of you who have never taken your dogs racing – you really do not know what you are missing – find your nearest meeting and go along and see what happens. They – and you! – deserve the fun.” This meeting was attended by 22 Afghan Hounds and 27 others: 4 Lurchers, 4 Pharoah Hounds, 3 Salukis as well as Whippets, Border Collies, Siberian Huskies, even Jack Russells and 5 Border Terriers. In the 260s, the best Afghan time was 22 seconds; in the 440 metre run timings varied between 45 and 55 seconds; with some sub seven-second times in the 100 metres. What fun and yes, the dogs do deserve it! But Afghan Hounds have a special heritage; they had to run fast over some of the rockiest, most uneven, toe-crunching, tendon-testing ground in the world. And if they weren’t successful hunting dogs, they didn’t last! Sadly, unlike sporting dogs, the best athletes are not preferred in breeding plans here, the needs of the show ring and the desired ‘breed-type of the day’ receiving a higher priority.

As far as their use in the hunting field goes, Sir Harry Lumsden, when with the British Army in Kandahar at the time of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, was not impressed by the hounds he saw, writing: “The dogs of Afghanistan used for sporting purposes are three sorts: the greyhound (Afghan Hound), Pomer and Khundi. The first are not formed for speed and would have little chance on a course with a second-rate English dog, but they are said to have some endurance and, when trained, are used to assist charughs (hawks) in catching deer, to mob wild hog, and to course hare, fox, etc.” Later, a Major Mackenzie wrote to advise Drury in his British Dogs of 1903, to say that “The sporting dog of Afghanistan , sometimes called the Cabul Dog, has been named the Barukhzy Hound from being chiefly used by the sporting sirdars of the royal Barukhzy family. It comes from Balkh, the north-eastern province…” going on to describe how one hound killed a leopard that had seized her pup. This would have been some hound, both in size and determination. Drury provides an illustration of such hounds.

Mackenzie went on to describe the hounds in the hunting field: “They usually hunt in couples, bitch and dog. The bitch attacks the hinder parts; while the quarry is thus distracted, the dog, which has great power of jaw and neck, seizes and tears the throat. Their scent, speed and endurance are remarkable; they track or run to sight equally well. Their long toes, being carefully protected with tufts of hair, are serviceable on both sand and rock.” He gave their size and weight as from 24” to 30” and 45 to 70lbs. The ones he used were fawn or bluish-mouse, always darker down the spine, with a smooth velvety coat texture.

In Croxton Smith’s Hounds and Dogs of 1932, Mrs Amps also gave an idea of their sporting use: “The quarry, a small very swift deer called Ahu Dashti, is hunted by Afghan Hound with the aid of hawks…The young birds and Afghan puppies are kept together, fed on the flesh of deer. When fully grown, the hounds are loosed after a fawn and the hawks flown at it…The Ahu Dashti or chinkara, as it is known in Indian, is so swift that it is said that, ‘The day a chinkara is born, a man may catch it; the second day a swift hound; but the third, no one but Allah.’” She went on to describe hearing of a pack of chinchilla hounds, always grey with black points. She wisely stated that: “Many of our breeders and judges today clamour for size, for bigger hounds at any cost. The Afghan Hound is, or should be, of the greyhound type but sturdy, compact and capable of endurance in order to enable him to hunt all day over the barren, rocky, precipitous mountains of his own land. The struggle for height so often results in coarseness or weediness at the expense of quality. The origin of the Afghan Hound is lost in the mists of antiquity but his Afghan master has kept the breed unaltered for some two thousand years. It seems a pity to alter it now for the English show bench.” There goes a lament echoed in so many sporting breeds of dog.

Mrs Amps would not have liked the show reports on her breed in recent years. One, in 2010, read: “It has been a few years since I judged our breed and I was very shocked and disappointed to see some drastic faults which are coming in. Several were very narrow throughout, bordering on slab-sided and very thin…a lot had soft muscle…” Another 2010 judge reported: “Quite a few of the entry lacked forechest and depth of chest…” A year earlier, one judge wrote: “Having started with two male Afghans in the 1960s, each decade I see less of what attracted me to this wonderful hound. The smooth springy gait is being replaced by short jerky movements more befitting Zebedee on Magic Roundabout.” Another wrote: ”I found the front assembly of many hounds was disappointing.” A third one gave the view that: “We are I think at a crossroads and if we are not careful the qualities we have in our breed could easily be lost…” These comments from experts in the breed are worrying and the faults listed extremely serious in a sporting breed, a sighthound especially.

It seems perverse for fanciers here to see a distinctive breed from a remote country, to admire its features and characteristics developed by faithful devotees over many centuries, only to disrespect its heritage by breeding hounds quite incapable of carrying out their original function. It was that function that gave us the hound; in the evolution of sporting dogs function always decided form. The challenge now for Afghan Hound breeders is to restore the breed to its classic phenotype and stop breeding for false points like profusion of coat, flashy movement and purely cosmetic appeal. This is a sighthound breed well worth saving and the challenge is on.