712 HUNTING DOWN THE BEST HPR

HUNTING DOWN THE BEST HPR

by David Hancock

The all-rounders from mainland Europe, the hunter-pointer-retriever breeds from across the channel, have come to Britain in increasing numbers in the last half century or so. But are we importing the best breeds? The German breeds are well established here on merit, the Hungarian dog is clearly widely favoured and the Italian breeds attract a devoted following, but there are many more to be considered. We are spoiled for choice.

The all-rounders from mainland Europe, the hunter-pointer-retriever breeds from across the channel, have come to Britain in increasing numbers in the last half century or so. But are we importing the best breeds? The German breeds are well established here on merit, the Hungarian dog is clearly widely favoured and the Italian breeds attract a devoted following, but there are many more to be considered. We are spoiled for choice.

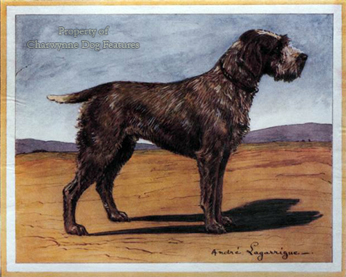

When working in Germany, near the Dutch border, in the 1960s, in challenging wildfowling country near the Dummersee, I was very impressed by the Korthals Griffon, developed from a blend of Barbet, French hunting griffon and German gundog blood. The skill of Korthals, a wealthy ship-owner’s son, who, although Dutch-born, lived in Germany as kennel-master to Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels in the late 1800s, was in the successful use of hound blood, a cause of temperament failings and undesired scenting traits in previous hound crosses in pointer-hound blends. Seeking a wildfowler’s dog, suitable for the Dutch polders, drained but often boggy land, Korthals began in the early 1870s with seven carefully-selected coarse-haired dogs from Germany, France and Holland. He eventually bred a number of outstanding dogs, strong physically and mentally yet still biddable, sharp-eyed and determined, robust and waterproof-coated, with immense stamina and impressive hunting abilities. Soon to become known as the pointing griffon, their blood has since been used to upgrade the performance of similar gundog breeds, including the Drahthaar. Korthals declined to name his breed the ‘rauh-haar’ or German rough-haired pointer.

As a working gundog, the Korthals Griffon, once the first choice of the Dutch and German aristocracy, has gained a considerable reputation as a game-finder and is ideally suited to finding woodcock in winter and partridge in spring. The breed first arrived in Britain a century ago, with classes given to the breed at the Barn Elms show in the jubilee year, but it did not gain KC-recognition until 2008, with the first litter born here in 2003. Smaller than the GWHP and the Spinone, the Korthals Griffon has a goat-haired coat slightly longer than its German cousin and of a different texture from that of the Spinone. The Korthals Griffon has a distinctive beard and eyebrows, and is favoured in steel-grey, with parti-coloured brown and white or orange-red and white also featuring; the coat texture is harsh and rough, a little like a brillo-pad to the touch, never frizzy, curly or woolly, but with a softer thicker undercoat beneath, providing the waterproofing so vital in a wildfowlers’ dog. I strongly recommend them.

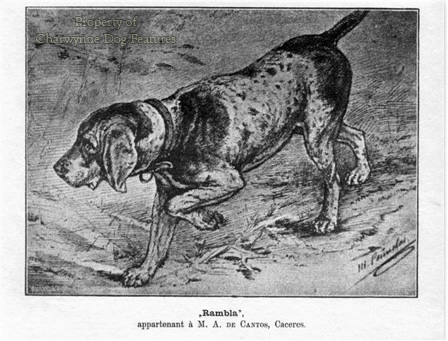

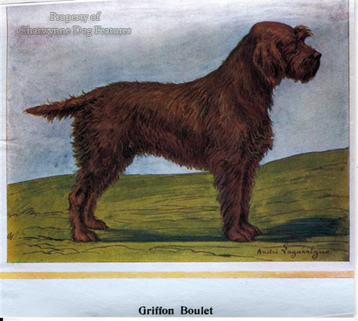

Another pointing griffon variety is named after its creator, the Boulet Griffon, developed using even more Barbet blood, in France. Emmanuel Boulet, a wealthy French industrialist, was advised by the renowned sporting dog authority of that time, Leon Vernier, and after a decade of trial crosses, produced two particularly talented gundogs, Marco and Myra, now behind every soft-coated griffon of that name. This soft coat comes from the waterdog blood of the Barbet, possibly the original waterdog of Europe. Boulet sought the ‘dead-leaf’ colour in the coat of his breed, to blend with the vegetation of his favourite shooting ground, the Londe forests. Another griffon pointer with waterdog blood is the Pudel-pointer of Germany, created allegedly from a mating between a forester’s black Poodle and Kaiser Wilhelm II’s best English Pointer, Tell. The desired blend was one quarter Poodle to three quarters pointer, but in time Drahthaar blood was introduced to produce a more determined hunter and more robust dog.

The creators of both the Boulet and the Korthals pointing griffons prized the blood of the ancient French water-dog, the Barbet, enough to base their foundation stock on it. Now there is renewed interest in this unspoiled fussless breed here. The wildfowlers’ choice even before the development of firearms, the Barbet is still valued by the knowledgeable, with an annual get-together, an international one, in France each year. Stubbs portrayed the breed and whiptail enthusiasts should be aware of the breed’s resurgence. With only 6-700 in existence world-wide, an English fancier Wendy Preston is striving to popularise the breed here and deserves support; the genes of this ‘great rough water-dog’ are important now that inbreeding coefficients are under scrutiny in many pedigree breeds.

The Slovakian rough-haired Pointer has only existed since 1950, created from a blend of the Bohemian rough-beard, now known as the Cesky Fousek, the GWHP and the Weimaraner (as its coat colour betrays) but is steadily gaining ground in the UK. Some 300 have now been registered here, mainly owned by those who work their dogs. Of the dozen or so that I have seen, the variations in coat texture have been quite noticeable. Commendably, these early British owners have made good use of their dogs, gaining field trial awards and success in spring pointing tests, agility and obedience tests. The Ansona and Stormdancer kennels have so far led the way.

A pointing griffon better known here is the Italian Spinone, which has a roan-coloured Otterhound look to it, although there once was a white version, the Spinone Alba. The Spinone is now registering 3-400 dogs each year with our KC, with our Pointer producing around twice that number each year. Not long ago, in Italy, 20,000 English Setters and 15,000 Pointers were registered annually against only 1,500 Spinoni and 1,000 Bracchi. If the Spinone prospers here as the Weimaraner and GSP have, soon we could be seeing more registrations of them each year than of our own Pointer. In welcoming new breeds we must also look after our native ones.

The short-haired pointing dogs of France, or braques, have never found favour in Britain, despite the immense popularity of the German equivalent and the growing interest in the Bracco from Italy. But then, neither too have the French epagneul or setter-like gundog breeds from France, apart from the admirable Brittany, now achieving deserved recognition here. But discerning gundog men here who favour the German short-haired Pointer might well be inclined to look at the French braques, if only their merits were on show; it is not exactly the case that our sportsmen are set in their ways and breeds, as the astonishing rise in popularity of HPR breeds from the Continent since the Second World War amply demonstrate.

The French have quite a collection of braques or pointing breeds: the Braque d'Auvergne (recently introduced into Britain), the Braque Saint-Germain, the Braque de l'Ariege, the Braque du Bourbonnais, the Braque Dupuy - with few specimens remaining - as well as the Braque Francais in two sizes. They also have a good range of what we would call setters - their epagneul breeds: Breton, Francais, Picard, Pont-Audemer and Bleu de Picard. Despite this, many of their sportsmen use our gundog breeds. Now that our sportsmen have got used to the concept of all-round gundogs or hunt, point and retrieve dogs, the French breeds might in time have the appeal of the German breeds. The Brittany is well established here and the Braque du Bourbonnais already introduced. The Bourbonnais Pointer is shown at overseas dog shows, with over 100 registered annually, after nearly disappearing in the 1960s-70s. Some are born tail-less or with just a rudimentary tail. A distinctive breed, giving an impression of power without losing elegance, the coat colour shades in this breed have been variously described as faded lilac or peach blossom, achieved by the overall effect of the mottling of maroon-coloured spots or creamy-brown joined-up ticking. I have heard this breed described as a short-haired Brittany in North America but my French colleagues do not support this. It is good to know that such a distinctive sporting breed has been saved.

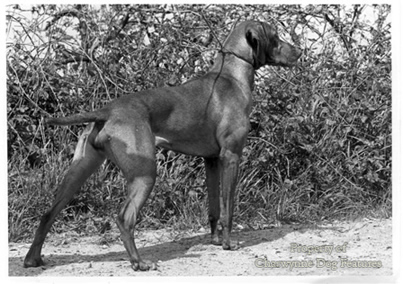

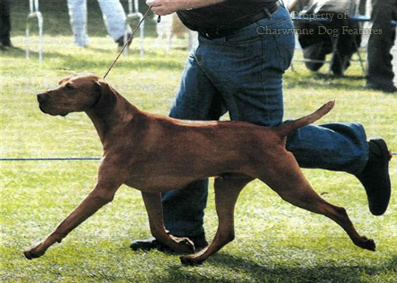

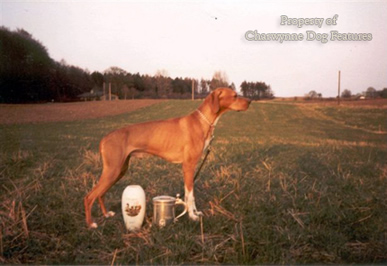

The golden braque or Hungarian Vizsla has a coat colour I have only seen matched by the Portuguese Partridge Dog and the Danish Hertha Pointer. The latter has been described as a variant of our Pointer, but despite some distant infusions of Pointer blood, now has every right to be recognized as a distinct breed, mainly thanks to the ceaseless endeavours of devotees like Jytte Weiss. Its highly-individual coat colour ranges from clear yellow-dark lemon to deeper orange-red, with shades of brown being discouraged. First seen around 1864 and from a bitch called Hertha, later Old Hertha, allegedly from the Duke of Augustenborg’s kennel, which specialized in chestnut-red pointers and was famed for its hunting dogs. It has a different head structure from the Pointer and characteristic white star face markings.

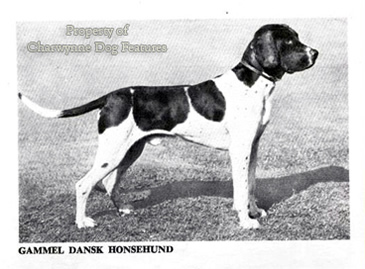

The Danes also have the Old Danish Bird Dog, the Gammel or Gamle Dansk Hoensehund, a short-coated pointer with a mainly white coat, with liver or lemon markings. First recognized by the Danish Kennel Club in 1960, there were 244 registrations twenty years later. There are special hunting trials for the breed. It resembles an English Pointer with hound blood, the dewlap being unwanted in many braques. Little known outside Denmark, it is now more an all-round hunting dog rather than a specialist bird-dog and already has a reputation as a tracker, benefiting from its ‘blodhund’ ancestry. The breed is sometimes called, in Denmark, the Bakhund, after its saviour from extinction, the sportsman Morten Bak.

The Perdiguero or Portuguese Pointer is a yellow-brown or chestnut coated, short-haired, strongly-muscled dog, once known as the Perro de Mastra, and developed by the Portuguese royal family and other noble families as a hawking dog. An athletic dog, moving with power and grace, with a calm and yet lively temperament, just under 22 inches at the withers, around 50lbs in weight and stronger-headed than many breeds of this type. In adjacent Spain, the Perdiguero de Burgos and Navarro, are heavier dogs, more like the Bracchi of Italy, more hound-like and with the Navarro coming in a setter coat too. Both Spanish breeds are not just bird-dogs but used on four-legged quarry too, as all-round hunting dogs.

The Bracco Italiano, the most hound-like gundog breed, can be chestnut and white or chestnut roan (from the old larger heavier Lombardy dog), orange and white (from the old lighter and smaller Piedmontese Pointer, used in the more mountainous areas) or orange roan, with a fine but dense glossy coat. A fairly large dog weighing from 55 to 90lbs and standing around two feet at the withers, it has a distinctive head, with a shallow stop, a Roman nose and a throaty heavily-flewed neck. Developed to work on small game, with quail and woodcock its traditional quarry, but used also on hares and even wild boar, although not to the extent the German pointers are utilized. In Italy they have more field trial entries than any other breed. Here they are being used as picking-up dogs, excelling on runners.

The braque family of gundogs and the pointing griffons are either late additions to our sporting scene or hardly known to us at all. In Victorian times, British gundog breeders had such a high reputation that our breeds ruled the sporting world, both in the new world and the old. It is surely for each nation to conserve its own native breeds but gundogs from afar have a role, not only introducing new blood into inbred lines but bringing in too wider-ranging hunting skills. For a century each gundog breed here has been genetically isolated; in the next century we need to open our minds to the health and vigour aspects of our dogs’ health and prize virility much more fully. Unexploited gundog breeds from abroad could play a role in such a reappraisal, one long overdue.