697 THE RETRIEVER FROM CANADA

THE RETRIEVER FROM CANADA

by David Hancock

It is forgiveable in these days of high quality, increasingly precise, sporting firearms to overlook the fact that a century and a half ago, shooting was, literally, very much more a ‘hit and miss’ affair. Gundogs, especially those supporting wildfowlers, had to be rather special dogs, versatile and skilful, as well as extraordinarily robust. Our trusty retrievers still serve us well in this respect but the widespread use of decoy dogs, to bring the wildfowl either within range of the guns, or to entice them along ever-narrowing netted channels, is unappreciated. Much of the construction of duck-decoys here was inspired by the Dutch. They have conserved their decoy dog, the Kooikerhondje; we have lost ours – perhaps to Canada!

It is forgiveable in these days of high quality, increasingly precise, sporting firearms to overlook the fact that a century and a half ago, shooting was, literally, very much more a ‘hit and miss’ affair. Gundogs, especially those supporting wildfowlers, had to be rather special dogs, versatile and skilful, as well as extraordinarily robust. Our trusty retrievers still serve us well in this respect but the widespread use of decoy dogs, to bring the wildfowl either within range of the guns, or to entice them along ever-narrowing netted channels, is unappreciated. Much of the construction of duck-decoys here was inspired by the Dutch. They have conserved their decoy dog, the Kooikerhondje; we have lost ours – perhaps to Canada!

Useful dogs were especially prized by early colonists in places like Australia and North America, as the cattle-dog from down-under and the retrievers from Chesapeake bay and Nova Scotia still illustrate today. It could be argued that these two gundog breeds are not locally-developed breeds but our Norfolk Retriever and our Red Decoy Dog, respectively, revived. Now a red-coated decoy dog is back, as the charming and handsome Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. Over 160 are registered annually and they feature in agility and obedience as well as gundogs.

In naturalist Sir Ralph Payne Gallwey's book Duck-decoys, of 1886, there is a good depiction of a red decoy dog, working with a black water dog; it displays the appealing red-gold coat once common in Golden Retrievers. This coat colour is remarkably difficult to pick up when working gundogs or patrolling with guard dogs at night. Coat colour matters more in working conditions than many show breeders realise. A heavily-feathered tail also has its uses, not just as a rudder in water or in providing balance on tight turns. The skill of the decoy dog lies in giving the inquisitive ducks only fleeting and seemingly tantalising glimpses of its progress, usually its tail's progress, through the reeds and undergrowth, taking great care never to frighten them or even give them cause for suspicion. Before the use of firearms and indeed in the days when their range was very limited, these dogs must have been enormously valuable to duck-hunters. In the 19th century, just 10 decoys around Wainfleet in Lincolnshire produced 31,200 head in one season, mostly for the London markets.

The distinctive feature of dogs used in this way was the well-flagged tail. Their colour was usually fox-red, leading to some being referred to as fox-dogs, partly also because foxes will entice game by playful antics in a very similar vein. Clever little fox-like dogs have been used in many different countries in any number of ways in the pursuit of game: in Finland, their red-coated bark-pointer Spitz breed transfixes feathered game by its mesmeric barking whilst awaiting the arrival of the hunters; in Japan, the russet-coated Shiba Inu was once used to flush birds for the falcon and the Tahl-tan Indians in British Columbia hunted bear, lynx and porcupine with their little black bear-dogs, which were often mistaken for foxes.

In his Duck Decoys (Shire Album 361) of 2001, Andrew Heaton writes on decoy-dogs: 'A dog trained and used in working a decoy in this manner needs to be extremely obedient, able to respond to silent commands and carry out its duties without taking notice of the encroaching wildfowl. The dogs were traditionally given the name of Piper. Such dogs tended to be fox-like in form, small with a bushy tail and a reddish colouration.' Ferrets, cats, tame foxes and even a rabbit have been tried in this role but proved untrainable.

At the end of the 19th century "ginger 'coy dogs" were frequently to be seen alongside lurchers in gypsy camps, especially in East Anglia. James Wentworth Day, the celebrated country sports writer of that time, refers to them in his 'The Dog in Sport' of 1938, linking them with the 'Fen Tigers', the rough countrymen who cut sedge and dug peat from the Fens and were skilled wild-fowlers. In his A Dictionary of Dog Breeds of 2001, the zoologist Desmond Morris describes the Red Decoy Dog as a small rufous dog employed to lure wildfowl into nets and suggests that their behaviour in doing so was modelled on comparable behaviour in foxes. Because no native pedigree breed in this mould has been handed down to us, very little reference is made nowadays to these gifted and at one time invaluable dogs, rather as the ancient water-dogs are rarely acknowledged in the histories of our gundog breeds. Both decoy-dogs and water-dogs were usually handled by the humbler hunters like farm labourers and gypsies and so very little has been written about them.

In Europe it seems that the Dutch in particular had perfected the art of duck decoying, with the word itself coming from their word endekoy, a duck cage. The first duck decoy in Britain was built by a Dutchman, Hydrach Hilens, just over three hundred years ago in St James's Park for Charles the Second. Such a decoy usually consists of a small shallow pond secluded by trees with a number of "pipes" leading off it, each about 60 metres long. These pipes or caged tunnels are six metres wide and four metres high at their entrance but narrowing right down to the decoyman's net.

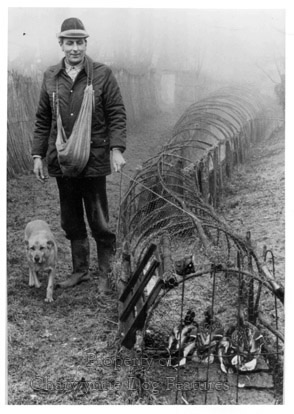

Along the curve of the pipe the decoyman (or kooiker in Holland) is concealed behind reed-screens. One of the few remaining in Britain is a joint venture between the National Trust and the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Naturalists' Trust at Boarstall. This decoy is marked on the 1697 map of the Manor of Boarstall in the Buckinghamshire County Record Office. Tame "call ducks" are no longer used here but Daniel White who once worked this decoy for over 60 years used six large Rouen call ducks. The yearly average of duck taken here at the end of the 19th century was 800. I believe there are only four kooikers still operating in Holland but they have retained their specialist breed of decoy dog, the Kooikerhondje, a small red and white spaniel-like dog; one of these is now working at the Boarstall decoy. A Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever is working at the decoy on the Berkeley Estate in Gloucestershire. England has lost its native red-coated decoy dog, which surely could still have been useful if only to those wishing to ring, photograph, paint or just study wild duck.

Both the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever from Canada and the Kooikerhondje from Holland are now established here. They make attractive companion dogs, with happy natures and a handsome appearance. The Canadian dog is around a foot and a half high, and comes in all shades of red or orange, with lighter markings under the tail and white markings on the chest, toes and tip of tail. The Dutch dog is a little smaller, mainly white with orange-red patches breaking up the coat. The Welsh have their springer spaniel and the French their Brittany, both featuring that attractive rich red with white coat, although the French dogs are more often red-roan. To see a sporting dog in this rich red hue, working in the sunshine, active and enthusiastic, is for me one of the most satisfying sights on any shoot. Their coats seem to glow with health and vigour. It is often a colour favoured by wildfowlers and may be more than a preference in colour; so many breeds with waterproof coats have a reddish look to them.

Some wildfowlers, hunting the open shoreline have used decoy-dogs to lure ducks within shooting range by throwing sticks for the dog to retrieve and arousing the natural curiosity of the birds. The skill of the hunter lies in throwing the stick for the dog the right distance at the right moment so that the ducks are not frightened away by the menace of an advancing dog, but made curious by the enticing waving of its bushy tail. The dog makes a normal retrieve of the stick but does so in a playful manner with plenty of tail-wagging. This decoy dog does not entice the birds by deliberately frolicking about, as foxes have been seen to, but is used essentially as a retriever of sticks. This playful retrieve however does lure the duck within range of the hunter's gun. This is however more work than play; before the use of firearms with appreciable range, such dogs would have more than earned their keep.

The Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever is widely favoured in Scandinavia, where working tests are held for them. A tolling working test is a hunting trial using canvas dummies in lieu of cold game, embracing tolling and retrieving, aiming to rehearse and instill basic retriever skills. Tollers are expected to feature the true retriever double coat, the outer for water-proofing, the inner for insulation. The toller has been described as a hunter’s dog, rather than a trainer’s dog. They can often follow their instinct rather than their handler’s wishes! They can vary in size and weight of bone, as well as degrees of obstinacy, but their handy size, handsome appearance and soft natures have won them many loyal fanciers.

I see many resemblances to the Golden Retriever in the Canadian decoy-dog both in their sunny nature and their perpetually waving tails. A Golden was quite recently used as a decoy dog in East Anglia, charming many visitors. We may not, in these sophisticated times, need all of the wide-ranging skills of our dogs, but they need to have them exercised and we should respect their innate desire to be active, their instinctive interest in hunting and their inherent talent for serving mankind.