694 COURSING THROUGH OUR VEINS

COURSING THROUGH OUR VEINS

by David Hancock

Misconceptions, including some rooted in misinformation, formed a significant part of the anti-hunting campaign at the end of the last century. Extremists rarely value the truth and lazy journalists regularly misinform the general public on subjects where public knowledge is limited. Two ‘facts’ in particular influenced public attitudes to hunting with dogs: one was the widespread belief that a pack of Foxhounds always broke up a fox whilst it was still alive. Every statement, provided by experienced knowledgeable sportsmen, that the lead hound, if only as a matter of canine pride, killed the fox immediately, was pooh-poohed as ‘propaganda’. And the widely-held view that hare-coursing had the sole purpose of killing hares, rather than comparing the running and turning skills of a pursuing brace of sighthounds, soon became accepted wisdom. Pro-hunting lobbyists just couldn’t swim against the tide and the ‘antis’ exploited this quite shamelessly.

Misconceptions, including some rooted in misinformation, formed a significant part of the anti-hunting campaign at the end of the last century. Extremists rarely value the truth and lazy journalists regularly misinform the general public on subjects where public knowledge is limited. Two ‘facts’ in particular influenced public attitudes to hunting with dogs: one was the widespread belief that a pack of Foxhounds always broke up a fox whilst it was still alive. Every statement, provided by experienced knowledgeable sportsmen, that the lead hound, if only as a matter of canine pride, killed the fox immediately, was pooh-poohed as ‘propaganda’. And the widely-held view that hare-coursing had the sole purpose of killing hares, rather than comparing the running and turning skills of a pursuing brace of sighthounds, soon became accepted wisdom. Pro-hunting lobbyists just couldn’t swim against the tide and the ‘antis’ exploited this quite shamelessly.

Have foxes and hares benefited from such conspiracies? Or is it little to do with animal welfare when the truth is known. Maimed foxes can survive a fox-shoot. Not many hares escape a hare-shoot. A study in the May 2005 issue of Animal Welfare, the journal of UFAW, showed that up to 50% of foxes shot with shotguns were wounded not killed. I understand that in no coursing season in the last two decades of the twentieth century were more than 300 hares, of the 2,000 coursed, killed. Just under 400,000 hares were shot annually on non-coursing estates for control purposes during that time. And the hare was welcome on coursing estates. Sport is about seeking a contest not extermination; the coursing community respected hares. It is the hunter’s natural instinct to preserve what he hunts. The Veterinary Association for Wildlife Management has stated that hunting is the natural and most humane method of controlling populations of all four quarry species and is a key element in the management of British wildlife in general.

The management of British wildlife in general has been in the hands of countrymen throughout our history, but now, the town-dwellers are the masters, whatever the effect on our precious wildlife. Coursing is over 2,000 years old; suddenly, modern man, whilst rapidly destroying the planet, knows best. The biggest single component attending the Waterloo Cup comprised working class men from the north of England, Liverpool especially. Their elected representatives have achieved what no Danish king or Norman knight could do: deny the humble peasant his right to catch his own supper. The ban on hunting with dogs has been called an act of class war, and the class worst hit has been the working man, not the wealthy man. It takes near-genius to draft one act which punishes both wildlife and the ordinary far-from-wealthy countryman to a greater degree than hitherto obtained in history.

A regulated country sport with strict rules, like coursing, brings with it respect for the quarry and the country being used. As Professor Roger Scruton, writing in the Winter 2009 issue of the magazine ‘Hunting’ put it: “The opponents of hunting see it as a kind of primitive battle, in which the quarry is overcome by unfair military tactics and a cruel war of attrition. For the hunt followers, however, the hunt is an equal contest, governed by rules of engagement which respect the hunted animal while giving the greatest possible scope to the hounds that are pursuing it. True, the quarry is singled out for a life and death struggle which it did nothing to provoke. But this ‘singling out’ exalts the fox or stag in the eyes of its pursuers and imposes on them the ethic of fair play.” This ‘ethic of fair play’ used to be the leitmotif of country sports.

In his masterly Rural Rites, Hunting and the Politics of Prejudice, of 2006, Charlie Pye-Smith writes: “Anyone who wishes to ridicule the Act, and test it to the limits, will have no trouble doing so. Take, for example, the hunting of hares. It is illegal under the Act to hunt hares with dogs. However, you can hunt hares with as many hounds as you like providing you are pursuing hares which have been shot.” If any perverse sadist elected to maim hares with a high-powered air rifle, he could then legally course them. Is this truly how animal welfare should be enacted? Do-gooders so often end up being evil-doers. The rules of coursing did more for animal welfare than could any legal action arising from the words of this vengeful Act.

The Hunting with Dogs Act became so closely associated with the prohibiting of fox-hunting that the ancient sport of coursing became relegated; not many sportsmen spoke up for this well-regulated sport. One hundred and forty years ago, Delabere Blaine was writing in his immense tome Rural Sports: “Coursing, like other field sportings, has its advocates and its enemies; it also presents its bright and cloudy sides. It is not, indeed, fit that we should all be enamoured of the same pursuit; but it is proper that we should not underrate the amusements followed by others.” Those who respect and practise our ancient country sports failed to close ranks when this badly-drafted bill was being framed; there should have been a realization that ‘once the pistol was loaded, it could point in any direction’. The war-poet Charles Causley once wrote a heart-rending poem about a recruiting sergeant, to the effect that ‘he’s already taken our Tommy and Kate – and he’s coming back for more’. The law concerning hunting with dogs is in a real mess; this is neither good for animal welfare nor for country sports. Before the fanatics ‘come back for more’, we need to put this house in order, for the sake of our wildlife just as much as for our ancient country sports.

In an article published in a national shooting magazine in September 2003, a contributor, in a piece headed ‘What a waste of space’, expressed little sympathy for the hunting fraternity, asking what have they done for shooting? How the antis must have rubbed their hands in glee on reading that! As a direct consequence, I fielded a tirade from an enraged coursing Whippet owner, who ranted: “Are flying targets given a ‘start’ before being engaged; coursed hares are! Are hares specially bred and nurtured to provide running targets in the way that game-birds are as aerial targets? Are hares reared semi-tame before being released into the wild or the shooting ground? Game-birds are! Hares were coursed by two hounds only; are shooters restricted to two gundogs only on a walked-up shoot? Is the battue-line pleased when most of their feathered targets escape? Coursers expect that with furred prey.” When she calmed down, she agreed that none of these words, written in a magazine or spoken on the telephone helped the cause of field sports.

It did occur to me however, as she vented her spleen, that in both the hunting field and at the coursing match, the man on a horse in a coloured coat was in authority. Is it this sort of emblematic figure which seems to attract opposition so vehemently? It didn’t seem to bother that architect of extreme socialism, Friedrich Engels, when he rode with the Cheshire Hunt, or Vladimir Lenin whilst hunting in Russia. But it did offend Adolf Hitler who banned fox-hunting as his particular expression of cla ss-warfare. Perhaps, unlike the fascist Hitler, communists Engels and Lenin had time-honoured field sports ‘coursing through their veins’ as one of my rural neighbours in the great sporting county of Shropshire liked to argue about the feelings of rural sportsmen. Fascists and communists may not agree about field sports, but field sportsmen should.

ss-warfare. Perhaps, unlike the fascist Hitler, communists Engels and Lenin had time-honoured field sports ‘coursing through their veins’ as one of my rural neighbours in the great sporting county of Shropshire liked to argue about the feelings of rural sportsmen. Fascists and communists may not agree about field sports, but field sportsmen should.

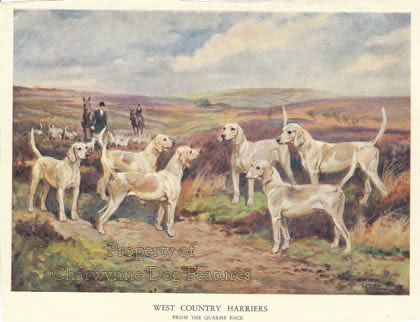

The fact that the Veterinary Association for Wildlife Management has stated that hunting is the natural and most humane method of controlling populations of all four quarry species and is a key element in the management of British wildlife in general, is surely a lead for us all. Before the pro-banners ‘come back for more’, we need no division amongst sportsmen and a much louder voice in getting the truth established. The ban has affected more working class hunters than any number of men mounted and in red coats. Look again at those depictions of the Waterloo Cup, whether on canvas or in old black and white photographs; the vast majority of the spectators wore cloth caps not top-hats. They have been badly let down by those feigning to protect their interests. And so has our wildlife, if the vets are to be believed. In four successive years in the 1980s, the winners of the blue riband event of coursing, the Waterloo Cup, each won - without killing a single hare between them. But don’t say this too loudly; it might attract attention!