683 COPING WITH A COCKER

COPING WITH A COCKER

by David Hancock

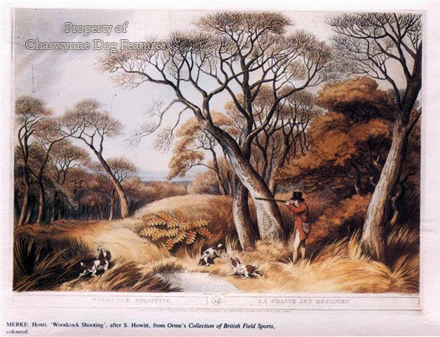

"The spaniel, in my opinion, is the most difficult of all dogs to break in a scientific manner, and this for one reason only, simply because his work takes him very frequently out of your sight in thick cover...his duty being for the most part to 'roust out' his quarry..."

"The spaniel, in my opinion, is the most difficult of all dogs to break in a scientific manner, and this for one reason only, simply because his work takes him very frequently out of your sight in thick cover...his duty being for the most part to 'roust out' his quarry..."

Those words from The Scientific Education of Dogs for the Gun, by 'H.H.', of 1920, give an instant impression of the task facing spaniel trainers, as well as indicating their time-honoured role. The late Brian Plummer would no doubt have crossed a spaniel with a working sheepdog to obtain that measure of human control needed! I have long been surprised at how tolerant of a lack of steadiness many gundog men are of their spaniels. Half a millennium ago, in his informative The Master of Game, de Foix was writing: '...a spaniel, if he see geese or kine, or horses, or hens, or oxen or other beasts, he will run anon and begin to bark at them', going on to accuse them of 'so many other evil habits'. I have known experienced gundog men reduced to hair-tearing exasperation whilst striving to educate a wayward Cocker. In many ways they are the terriers of the gundog tribe. But their advance in the early trials world was praiseworthy.

In 1920, only four Cockers competed at trials. Five years on and the figure had progressed to 41.In 1930, 63 participated, with the peak number of 73 being reached five years later. In 1924, that great spaniel man CA Phillips of the Rivington kennel was writing: “There is no doubt the Cocker has changed more quickly in appearance and requirements than any other of the Spaniel family, but this is chiefly by reason of the changed methods of shooting. For this reason, he has developed from the smaller unit of a team to the larger-sized ‘dog of all work’, thereby adding to his popularity – but we cannot have it both ways. If he is to fulfil the requirements of today as a working dog, he must be of such a build, and such a size, to meet these altered conditions.” He went on to observe that it is much easier to breed quality in the smaller dog than the larger one and that for the show bench size does not have the same importance. Size is always more significant than mere breed identity; this breed evolved for a working purpose.

General Hutchinson, in his valuable Dog Breaking of 1909, wrote that 'even good spaniels, however well bred, if they have not had great experience, generally road too fast. Undeniably they are difficult animals to educate...' The late Keith Erlandson once wrote that 'a good Springer should have the qualities of the Spanish fighting bull and the Zulu warrior', some combination! But he did describe Cockers as 'inveterate belly crawlers and the sight of one pulling himself forward by his elbows, hind legs stretched straight out behind him causes me such amusement, with a resulting breakdown in concentration...' Sounds like a dog literally pushing its luck to me! Erlandson also wrote: “A good Cocker reminds me of a combination between a Corsican bandit and a seven-year old dog fox. Basically, the Cocker needs more game to get it going than the Springer requires. Their attitudes are so different. Order the Zulu to charge a line of machine guns and he would charge without question. The Corsican would decline and take the guns by night attack.”

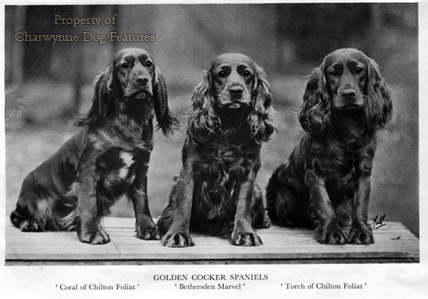

Erlandson handled the outstanding working Cocker FT Champion Speckle of Ardoon to an unprecedented trio of championship wins from 1972 to 1974, without ever being involved in a run-off. At a Game Fair Spaniel Test at Raby Castle, on a seriously testing hot day, she ran the opposing Springers into the ground. Cocker Spaniels can excel! The breed may have declined in the fifties but the 1980s was a decade of great progress for the working breed. Handlers like Denis Douglas and Jack Windle ensured that the breed reached for and attained the highest standards. The breed has long had distinguished handlers and kennels producing a distinct type: the Ware and Falconers alongside the Colinwoods, the Treetops and the Broomleafs. The Lochranza blacks showed up with their remarkable uniformity, with the quite striking Craigleith parti-colours producing such high-quality bitches in the 1960s.

The American spaniel expert, Carl P Wood, in his Sporting Dogs of 1985, (Gun Digest), wrote: 'Cocker Spaniels are excitable and emotional and should be handled with sensitivity and gentleness during training. They seem to know immediately when play stops and the boss gets serious. An act or motion that would not matter at all in play or roughhousing with a Cocker, if done at a 'serious' time, will cause emotional difficulty with many Cockers.' This is a subtle point, a perceptive one, but innate hot-headedness, allied to great sensitivity, in any breed, really tests the trainer, despite being rooted in an eagerness to perform. CA Phillips wrote on this aspect: “A really good working Cocker is quite the merriest and most delightful companion a sportsman can have, and if taken in hand early is almost as easily trained as any other breed of Spaniel…I find that if stopped early in life from chasing rabbits and hares, a Cocker is never so wilful and headstrong when he is taken in hand later on…”

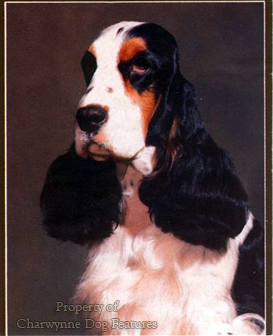

In 1947 the Cocker was the most popular pedigree breed in the country, with 27,000 registrations in that year. Such popularity is not always beneficial to a breed, but the breed does attract a sustained following. In 1956 there were just over 7,000 registrations. In 1971, there were still over 6,800. In 1980, there were well over 9,000 registrations, in 1990 nearly 13,000 and in 2000 well over 13,000 again. In 2008, the total breed registrations totalled well over 22,000, almost back to the levels of sixty years ago. But the show dogs for all their handsomeness, display worrying faults. The 2009 Crufts judge reported: “Forequarters are still a problem, with too many upright shoulders and short upper arms.” These are serious anatomical faults in a working breed and it is depressing to think such faults still allowed the bearers to qualify for the top show. A championship show judge reported that same year: ”a lot of them were very thin and had no substance, body or muscle to the upper thigh, some with vast amounts of hair left on the back legs trying to conceal extremely poor hind action and some were far too small.” Were the exhibitors of these dogs so ill-informed that they seriously thought such dogs could win? If not why enter?

Inherited defects are also a source of worry in this breed. Gough and Thomas list over five pages of breed-disposed health problems in the breed, some not breed specific but some potentially crippling. Honourable breeders can now avail themselves of two DNA tests: for prcd PRA (Progressive Retinal Atrophy) and FN (Familial Nephropathy), both hereditary diseases which are carried as simple recessives, so that the outcome of matings could be predicted. It is known that Cockers can be afflicted by entropion, PPM (Persistent Pupillary Membrane), distiachiasis, slipping patella, HD and dilated cardiomyopathy, but without mandatory testing of breeding stock or a faithful recording system, who knows the incidence rate? The Cocker Spaniel, the working type especially, is not, despite this list, more susceptible to inherited defects than many other pedigree breeds but urgent action is needed over monitoring the breed’s genetic health. This is an admirable native gundog breed which merits our very best care.

A couple of decades ago, the breeding base of the working Cocker was worrying narrow; FT champions such as Templebar Blackie, Monnow Mayfly, Ardnamurchan Mac, Speckle of Ardoon and Carswell Zero each had a deep developmental influence on today’s dogs, as indeed did the Jordieland Cockers of Jack Windle. In the show world the overuse of certificate-winning sires can narrow the gene pool too. The large numbers of Cockers registered each year diverts attention from the fact that nearly every Cocker goes back to Bebb, a famous winner from 1867 to 1873 and an even more famous stud dog. The lack of interplay between show stock and working dogs as far as breeding is concerned is an enormous pity. Cynics may say that show people are seeking beauty queens whilst sporting owners are only interested in performance  – well ahead of physical perfection. But when virility and vigour are desired ahead of beauty of form, then the health of the whole breed should come first. Gundog men sometimes describe the show dogs as over-furnished and gormless; show exhibitors say that the working specimens lack breed type and can be too headstrong. Perhaps the Kennel Club’s recent mandatory requirement for show judges of gundogs to attend a Field Trial at Open Stake level or an Open Gundog Working Test for the relevant gundog sub-group, before being considered to award Challenge Certificates will bring the two gundog worlds closer together.

– well ahead of physical perfection. But when virility and vigour are desired ahead of beauty of form, then the health of the whole breed should come first. Gundog men sometimes describe the show dogs as over-furnished and gormless; show exhibitors say that the working specimens lack breed type and can be too headstrong. Perhaps the Kennel Club’s recent mandatory requirement for show judges of gundogs to attend a Field Trial at Open Stake level or an Open Gundog Working Test for the relevant gundog sub-group, before being considered to award Challenge Certificates will bring the two gundog worlds closer together.

Gundog writers have expressed conflicting views on this breed. In his book Gundog Sense and Sensibility of 1982, (Pelham Books), Wilson Stephens wrote: “The Cocker, by nature a realist, is inclined to pessimism when things are not to his liking. In face of a known difficulty, a Cocker has the heart of a lion, but he is no enthusiast for forlorn hopes, and if asked to beat out a gameless piece of country is apt to treat the proposition with the contempt it deserves.” In contrast, the eminent working Cocker Spaniel man of that time, Peter Moxon, once wrote: “The Cockers are the anarchists, the Freedom Fighters of the gundog world. One day they will liberate a city, next day they sack a town and go on a drunken binge. They are unique. May they never conform.” I’ll drink to that!