674 BARKING UP THE WRONG TREE

674 BARKING UP THE WRONG TREE

by David Hancock

“The real historian is…a nuisance when we want to romance about 'the old days' or 'the ancient Greeks and Romans'. The ascertained nature of any real thing is always at first a nuisance to our natural fantasies - a wretched, pedantic, logic-chopping intruder upon a conversation which was getting on famously without it".

“The real historian is…a nuisance when we want to romance about 'the old days' or 'the ancient Greeks and Romans'. The ascertained nature of any real thing is always at first a nuisance to our natural fantasies - a wretched, pedantic, logic-chopping intruder upon a conversation which was getting on famously without it".

(C.S.Lewis, Miracles).

Does the Dalmatian truly have links with Dalmatia? Is the Mastiff really a Molosser? Are the words sighthound and gazehound actually synonymous? Should the Greyhound more accurately be called the Grehound? Why didn’t the Maltese call their hound a Pharoah Hound? What is the difference between a water-dog and a water spaniel? Did the Romans really find mastiffs in Britain when they landed? Was the bandogge a tied-up yard-dog or a leashed seizing dog freed at the culmination of the medieval hunt? Did the spaniels originate in Spain?

The more I look at the recorded histories of the modern pedigree breeds of the domestic dog, the more I understand Thomas Carlyle's statement that 'History is a distillation of rumour' and Henry Ford's rightly much-criticised and intentionally hyperbolic opinion that 'all history is bunk'. And whilst I am all for a little romance in life, when the desire for a romantic background overcomes the surely overwhelming need for the truth, then the latter must regain the high ground. With so many of the official histories of our contemporary reeds of pedigree dogs the records may not be all 'bunk' but they do contain too much 'bunkum'. Lazy plagiarism, sloppy or non-existent research or casually failing to corroborate one author's opinion all add up to one thing - faulty historical records.

Two hundred years ago, Lessing wrote that absolute truth belongs to God alone. A century before him, Sir Henry Wotton wrote of the 'happy man' "whose armour is his honest thought, and simple truth his utmost skill." History may well have an element of 'bunk' in it; recorded history can often be the work of scholars who for all their intellectual prowess wouldn't know a Segugio from a Shiloh Shepherd Dog or a Slovac Cuvac from a Xoloitzcuintli and absolute truth may be simply divine. But even if the truth can spoil a good story, it must be respected, if only for its ensuing value.

In my working life I was responsible, at various times, for the management of four different museums and an art gallery and have a lasting respect for curatorial skills. Recorded history must rely on known facts and the best possible conclusive reasoning. The tendentious relating of the history of the Mastiff by well-meaning but misguided breed historians like Wynn, Adcock, Kingdon and Taunton has misled many generations and never benefited the breed. Sadly, it is now commonly accepted that mastiffs are molossers, desp ite the Molossii not possessing mastiffs; I say sadly, because it has led to mastiffs being bred like mountain dogs instead of the heavy hounds they are.

ite the Molossii not possessing mastiffs; I say sadly, because it has led to mastiffs being bred like mountain dogs instead of the heavy hounds they are.

Accurate well-researched breed histories, ideally conducted by those "whose armour is honest thought and simple truth their utmost skill", make us realise what our dogs are for. Only then can we appreciate their often unseen instincts and offer stimulation, so that are spiritually happier. The invention of false provenances for any pedigree breed, however romantic or exotic, undermines the rightful heritage of the breed, is never necessary and contributes nothing to the breed itself. The next time you see a litter of non-pedigree working sheepdogs in Scotland and spot a goat-haired 'intruder' among the pups, there really is no need to check whether a Polish grain ship called at a nearby port a couple of months earlier. That's the way the gene pool works in this breed type, no help from Poland is required!

Forty years ago I was working in Germany with a colleague who was a displaced person from Yugoslavia. He had been an officer in the elite royal guard and was in permanent exile from what was then Tito's communist Yugoslavia. He was born in Dalmatia and loved dogs. A keen researcher, a sound historian and patriot, he had tried, throughout his life, to discover evidence of a credible link between his native Dalmatia and the breed of dog known as the Dalmatian. With commendable honesty, he confessed to me that despite all his endeavours, he could find not a shred of evidence beyond the name. My experience has been the same.

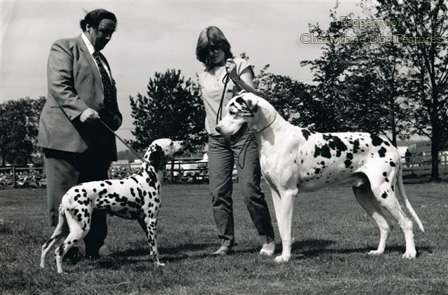

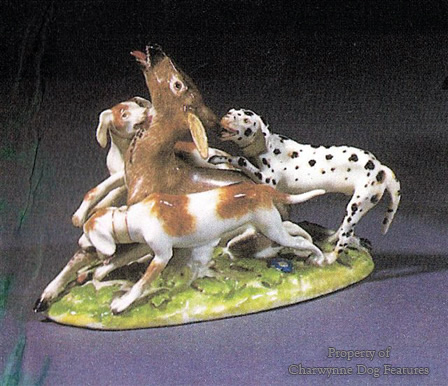

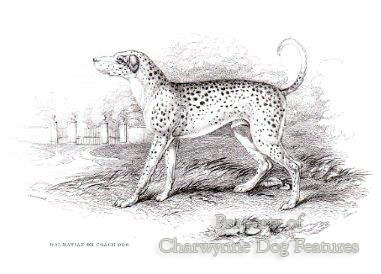

Yet just about every book covering or referring to breeds of dog links the origin of the Dalmatian with Dalmatia. My own theory, which I am happy to have challenged, is that this breed name comes not from the country but the medieval Old French expression for a deer-hunting dog: dama-chien. A professor at a school of European languages has given me another view: that the French name for the game of draughts could be involved, i.e. jeu de dames chien, shortened to "dames chiens". Perhaps a French Dalmatian fancier will come up with some enlightening research one day. It will have significance; if they were hounds of the chase then they belong in the hound group, being judged as hounds.

But breed researchers seem to miss such important information so easily available to them. Why have Great Dane researchers not recorded the use of the blood of the Suliot dog in their breed? In 1863, the Rev. Charles Williams was observing that Lord Truro had one, brought from Germany, which he described as a boar-hound. He went on to state (using Colonel Hamilton Smith's research) that in the war between the Austrians and the Turks, the Moslem soldiers employed them to guard outposts. Many were captured by the Imperial forces and taken to what is now Germany. Colonel Smith saw them 'marching' in Brussels as mascots to regiments, describing them as roughly Shetland pony size and resembling " the Danish dog". One giant specimen was presented to the King of Naples.

The Suliots were the inhabitants of the Suli mountains in Epirus, a people of Greek-Albanian origin. This area of Epirus was occupied by the Molossii whose dogs have been wrongly associated with the short-faced or mastiff-type dogs. The Molossii were famous for their big hounds and huge flock guarding dogs. The Greeks themselves admired the quite separate so-called "Indian" dogs, the mastiff-type made famous by the Assyrians. I support the perhaps oversimplified summary of "Celts and Cretans for scenthounds, Arabs for sighthounds and mastiffs from Tartary".

Romancing a breed name can reach absurd lengths too. In the mid 1950s, I sometimes went rabbiting in the dry stone walls of the island of Gozo, whilst working in Malta. I admired the lithe, hyper-agile, smooth-coated, bat-eared hounds used by the farmers of Gozo, and indeed those of Malta too. Some years later I found they were being imported into the UK with the completely unjustified breed name of "Pharoah Hound" and a predictably phoney provenance. Dogs like this are found all along the Mediterranean littoral, from Portugal to Greece; the Sicilian equivalent being very much like the rabbit dogs of Malta and Gozo. Why invent a breed history and adopt a totally false name for such an admirable type of dog?

Even worse, Jesse, in his Researches into the History of the British Dog of 1866, like Turberville before him, presents The Master of Game's descriptions as referring to British dogs, whereas they referred to French ones. But even more misleading to Mastiff researchers is Markham's work in 1616; he tendentiously mistranslated Gratius's Cynegeticon to state that the Romans found 'mastiffs' on reaching the shores of Britain. As the distinguished American historian Jan Libourel has helpfully pointed out, what Gratius actually wrote was: "If you want a good hound, a trip to Britain would almost be worth it. The British dogs may not look much, but for bravery in combat even the famous Molossus does not surpass them." The word mastiff was never used in this much misused quote.

But another retriever, the one from Chesapeake Bay, has also been given a dubious origin. I agree with the forthright American writer Bede Maxwell when she records: "Every Chesapeake Bay historian inclines to start with Canton and Sailor, the waifs plucked from a sinking vessel off the Eastern Shore. This may be because the story of the rescue gained publicity in the press and became so preserved. It does not establish that these waifs were Adam and Eve of the breed." Canton was black. In 1877, Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dogs' owners came together to clarify what constituted a dog of their breed. A Captain Taylor spoke of: "…black dogs, smooth of hair, fierce, powerful, sagacious, with two skins, one hair, one fur, an india-rubber dog, smooth as glass." His fellow members roared that black dogs would be shot on sight in the Chesapeake as ducks would not come to a blind. Poor old Canton! More likely ancestors for the breed are the "Red Winchesters" imported from Ireland, or the rusty-red Norfolk retrievers shipped to Norfolk, Virginia. Retrievers are very much a British creation; I suspect too that the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever is a development of our 'red decoy dog' taken there by early colonists.

Retrievers have on the whole had rather more than their fair share of being singled out by the fantasists. The Golden Retriever was alleged (and sometimes still is) to have originated in a troupe of Russian circus dogs in Brighton. This despite the fact that golden pups occurred in black wavy-coated retriever litters with well-recorded regularity. The circus dogs were supposed to have been used around 1860. But Grant’s painting ‘A Shooting Party at Ranton’ of 1840, hanging at Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, depicts just about perfectly the Golden Retriever breed of today.

Most authorities, including the various encyclopaedias, state that our word spaniel comes from the French word epagneul, by way of the word for Spanish or of Spain, espagnol. But I believe that this is not so and that epagneul comes from the ancient French verb espanir – to crouch, rather as setting spaniels do, when working. I am also inclined to believe that spaniel is a comparable corruption of the Latin word explanere – to flatten out, from which the Italian word spianare – to flatten comes. An Italian acquaintance takes the view that the breed name Spinone comes from this source.

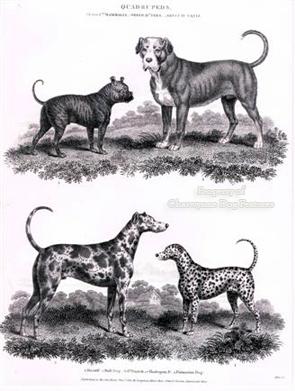

The less diligent researchers so often overlook the loose use of breed-type names in days gone by. The Sportsman’s Cabinet of 1803 records:

“It creates no surprize with the observant traveller to hear in Ireland, the pointer almost invariably called an English spaniel, as this, with a sportsman of that country might be considered only a slight deviation from the custom of this; but in the northern counties of England, where the shooting is so good, and the breed of dogs so excellent, it is not without considerable astonishment we hear pointers distinguished by the name of smooth spaniels, and setters by the denomination of rough spaniels. The real springing spaniel is with them termed a cocker, as the woodcock is there the only bird for which they are brought into use, consequently, but rarely to be seen in those districts; as, for instance, in some of the northern country-towns, where from thirty to forty brace of setters and pointers are kept in good state and proper condition, not one brace of well-bred and well-broke springing spaniels are to be found.” Breed researchers seeking past mentions of their favoured breed beware!

It is disappointing to read books on dogs from distinguished publishing houses or by otherwise respected museum professionals with ludicrous mistakes on our contemporary breeds of dog. One book, in its description of terriers, makes you wonder if you should laugh or cry. Take the words on the Sealyham: "In the mid-nineteenth century an extremely ferocious cat killer was produced in Wales through intensive breeding." But then turn to the section on terriers in another ‘best-selling’ book on dogs, look up the Skye terrier and you can regale yourself with the following: "In the early 1600s a Spanish ship came to grief against the rocks of the island of Skye in the Scottish Hebrides. Among the survivors were Maltese dogs that mated with local terriers and produced this new extremely pleasing and unique breed." Have you ever met a Scottish terrier man, even in these civilised times, who would want to mate his hard-bitten ultra-game bitches to a fluffy white lapdog of unknown ancestry?

But even sadder, is a dog book compiled by museum professionals who should command our respect, this book describes the Jack Russell terrier as a cross between the Fox Terrier and the Sealyham Terrier, despite the fact that the Jack Russell pre-dates the Sealyham. The Labrador Newfoundland is described as "a mastiff breed probably taken to Labrador by Basque fisherman (sic)". The Great Dane is described as "descended from the Mastiff and the Irish Wolfhound but it did not acquire the name Great Dane until 1772 when Buffon first introduced it." The distinguished cynologist Clifford Hubbard rightly refers to Buffon as 'Buffoon', and I can see why. He may have misheard ‘Grand Damois’ as ‘Grand Danois’ and changed the link from a function to a nation.

If anything, art historians are even more careless than curators. A decade ago I read a newly-published, fulsomely-reviewed and very expensive book on dogs in paintings. On writing to the author listing fifty mistakes, I received a curt note thanking me for my 'thoughtfulness'. How many breed enthusiasts, eager to learn, are being misled by such 'authorities'? I feel strongly that every breed of dog should be perpetuated in the light of its own heritage. We, the living, have the responsibility in our lifetime to keep faith with those who developed our magnificent breeds of dog and handed them on for our safekeeping. Authentic breed histories tell us what function our breeds had and what physical and mental characteristics are essential to that function. Why favour a breed if you don't care what it was for and what its genetic make-up is? For if we do not honour breed history we might just as well be breeding Euro-spaniels or Uno-hounds. Why not get it right?

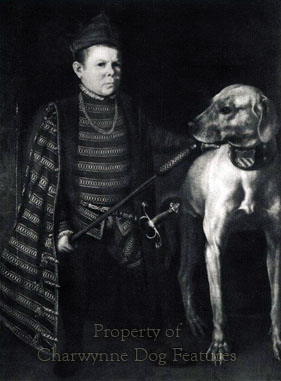

Even as diligent an author as Robert Leighton, in Edwardian times, took the view that the name bandogge or tie-dog referred to a secured guard dog. Sadly most of the revered Victorian writers on dogs copied from each other and in so doing cemented myths through sheer repetition. The words of Barnaby Googe in the 16th century linked the word bandogge with a tied-up house dog and, no doubt such a formidable dog made an effective protector of the house - and needed tying up! Rather than a tethered yard-dog, I believe there is ample evidence to indicate that the bandogge was a seizing dog, leashed during the hunt, until required as a catch-dog, to grip or hold big game that has been chased to near-exhaustion by the running mastiffs, of Great Dane type. This is a time-honoured way of hunting big game with powerful hounds, as the Assyrian bas-relief demonstrates. The 'band' or tie retains the savage dogs until the moment they are needed to risk their lives at the behest of man. There are countless portrayals of this in medieval paintings and engravings. There is an old English ballad of around 1610 which includes the lines: "Half a hundred good band-dogs, Came running over the lee." There is little indication of solitary tied-up yard-dogs in those words.

Disappointingly, I see expensive books on sporting dogs in which the word gazehound is used as a synonym for sighthound. I don't believe this is accurate, but persuading sportsmen and writers that this is so, rather like trying to break the inaccurate blurring of molossers with mastiffs, is going to be difficult. So many 'authorities' in so many books record these matters as accepted fact. In his valuable book The Dog in Health and Disease of 1867, the celebrated ‘Stonehenge’ records: "THE GAZEHOUND -- This breed is now lost, and it is very difficult to ascertain in what respects it differed from the greyhound." I don't believe the great man got that right. It is not justifiable to refer to this type as a breed; the sighthound has never been a breed.

In his Of English Dogs of 1576, the much-quoted scholar Dr Caius, wrote on the gazehound, which he listed separately from the Greyhound, although he himself was neither an expert on dogs nor a sportsman. He recorded: "Horsemen use them more than footmen, in the intent that they might provoke their horses to a swift gallop...and that they might accustom their horse to leap over hedges and ditches, without stop or stumble..." He described their modus operandi as that of "never ceaseth until he hath wearied the beast to death." Both these quotes hardly represent an account of a sighthound at work. It is a good description of par force hunting, in which medieval huntsmen rode hard, rather as in steeplechasing, after hounds which hunted by sight and scent. Bewick in his History of Quadrupeds of 1790 drew on Caius's words, listing the gazehound, as well as, quite separately, types like the Greyhound, the Highland Greyhound and the Irish Greyhound.

Par force hunting fell out of favour in Britain, the slower 'hunting cunning' using scenthounds replacing it. But boarhounds and staghounds across mainland Europe were employed in this style of hard-pursuit quarry-hunting for much longer. In otter hunting to 'gaze' meant to view the otter. Shakespeare wrote of "...the poor frighted deer, that stands at gaze...". The word 'gaze' clearly had a more precise meaning than merely 'see' or 'sight'; it has a Scandinavian origin and meant to fix one's eye on an object. Par force hounds located their prey by using scent and, once they caught sight of it, fixed their eye on it and went, often with reckless speed, wearying the beast to death, as Caius recorded.

But does it really matter if words like bandogge and gazehound are used too loosely? I believe it does if you want to understand the function of your breed and why its anatomy was constructed in the way it originally was. These terms have been misunderstood because researchers seek breed origins when they should be looking back for a function. Understanding a breed is for me a matter of identifying what the function of that type originally was and what kind of physique was demanded by that role. Only then can you truly appreciate why the upper arm needs to be the same length as the forearm, the need for a degree of bend at the stifle and the importance of muzzle length. Breed function matters!