670 HAVE THE SETTERS HAD THEIR DAY

HAVE THE SETTERS HAD THEIR DAY?

by David Hancock

In 2015, if the KC's registration figures are anything to go by, the setter numbers for that year indicated that, as a show dog the setter breeds appear to have had their day. It would be easy to counter that by arguing that since the gundog fraternity has moved away from the style of shooting needing purely bird-dog support then this decline is to be expected. But that argument is destroyed when you look at the reduction of earth-dog use by sportsmen then look at the high numbers of say West Highland White and Border Terriers being registered with the KC each year. In 2015, the setter breeds mustered by breeds: English - 289; Irish - 806; Irish Red and White - 64; Gordon - 234. If you then compare these figures with other gundog breeds used as bird-dogs you can see a dramatic difference: Weimaraners - 1,171; Hungarian Vizslas - 2,500 and German Pointers - 2,000. On this evidence our setters are on the way out. The setter-like foreign breeds of Langhaar and Large Munsterlander are not thriving here either, with 15 of the former and 94 of the latter being registered in 2015. We never bothered to conserve the Welsh or Llanidloes Setter or the black and white Scottish Setter. The all-black setter was never widely favoured.

In 2015, if the KC's registration figures are anything to go by, the setter numbers for that year indicated that, as a show dog the setter breeds appear to have had their day. It would be easy to counter that by arguing that since the gundog fraternity has moved away from the style of shooting needing purely bird-dog support then this decline is to be expected. But that argument is destroyed when you look at the reduction of earth-dog use by sportsmen then look at the high numbers of say West Highland White and Border Terriers being registered with the KC each year. In 2015, the setter breeds mustered by breeds: English - 289; Irish - 806; Irish Red and White - 64; Gordon - 234. If you then compare these figures with other gundog breeds used as bird-dogs you can see a dramatic difference: Weimaraners - 1,171; Hungarian Vizslas - 2,500 and German Pointers - 2,000. On this evidence our setters are on the way out. The setter-like foreign breeds of Langhaar and Large Munsterlander are not thriving here either, with 15 of the former and 94 of the latter being registered in 2015. We never bothered to conserve the Welsh or Llanidloes Setter or the black and white Scottish Setter. The all-black setter was never widely favoured.

One of the sadnesses in gundogs lies in the loss of old breeds, either through a lack of recognition or simply indifference to their fate. The English Water Spaniel once featured in the Kennel Club Stud Book, but is now lost to us. A number of distinct forms of setter were never perpetuated. The milk-white, curly-coated Llanidloes Setter would have provided a most distinctive element in our list of native setter breeds, had it survived. 'Stonehenge', writing at the end of the 19th century, described them as Welsh Setters, stating that their coats "would resist the wet and cold of the mountains in a marvellous manner." Is there not some proud Welsh patriot-sportsman out there who would be willing to re-create this lost breed? We have English, Irish and the Gordon Setter from Scotland, where is the Welsh representative?

Less likely to be restored is the Russian Setter, described by a number of authors in the 19th century. Lang wrote in the Sporting Review of 1839: "Then, for the first time for many years, I had my dogs, English setters, beaten hollow. His (i.e. those of his sporting host) breed was from pure Russian setters, crossed by an English setter dog which some years ago made a sensation in the sporting world from his extraordinary performances..." Not many sportsmen nowadays would dream of crossing two setter breeds, however good the blood, such is the dogma of pure-breeding. In his book on the setter of 1872, the great breeder Edward Laverack remarks that he had only ever seen one purespecimen of Russian Setter, owned by Lord Grantley in Perthshire.

Laverack mentions another old Welsh strain of setter, similar to the Llanidloes, but jet-black, stating that: "In their own country they cannot be beaten, being exactly what is required for the steep hill-sides." He also mentions the liver and white setters favoured in Cumberland and Northumberland, and the jet- black breed kept by the Earl of Tankerville. Interestingly, Laverack writes that the Duke of Gordon preferred black, white and tans in his setters, but kept black and tans too. As discussed below, you would not guess what the Duke's preference was from glancing at today's show rings for Gordon Setters. The breed standard of this breed states: Very small white spot on chest permissible. No other colour permissible. A few years back the best grouse dog in the country was a mainly white Gordon Setter. It would be wrong however to give the Laverack and the Llewellin Setters the sole credit for the development of the English Setter as a breed. In his The American Hunting Dog of 1918, published in New York, Warren H Miller, former editor of Field and Stream, writes: “There are hundreds of thousands of setters today who owe their descent to neither the Laverack nor the Llewellin strain. True, Mr Laverack did get up a happy nick that gave him dogs which could sweep all before them at the English field trials, and so were in demand, but he did not, in the nature of things, produce from his two dogs Ponto and Old Moll, more than a very small percentage of all the English setters in ‘blighty’.”

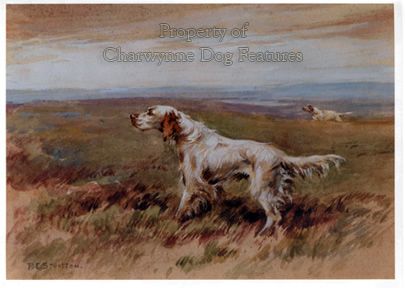

In his Champion Dogs of the World of 1967, Sir Richard Glyn wrote: "If one had to pick a dog, not a foxhound, as typical of English country life and the English country gentleman who lived it in the nineteenth century, then that dog would be the English Setter." Those words straightaway provide the frame for any word picture being painted of the English Setter. It was a breed chosen as the shooting companions of those with land or access to it and a life of ease, often dominated by country sports. The passion of such men for country sports not only shaped the English countryside but gave us our hounds, gundogs and terriers. In the time of the Stuarts, the setting dog was used to hold game birds to ground, often with a hawk overhead to keep the birds from flying, while a net was carefully drawn over them. Then with the introduction of firearms and later 'shooting flying', setters were needed, along with pointers, to indicate and then put up feathered game.

In pursuit of this function, the setting dog breeds developed both here and on the continent and were widely traded, with a high value on a trained and effective dog. Whilst our setter breeds were evolving here so too were the 'epagneul' breeds on mainland Europe. It is foolish for setter breed historians to claim a long and pure lineage for their favoured breed. Good setters were mated to other good setters irrespective of colour. The landed gentry went on their Grand Tours, sometimes taking their dogs with them through Europe and sometimes coming back with a dog which had impressed them. It was easier to bring foreign dogs into Britain in every previous century than the twentieth. But how sad is the state of this ancient English breed today.

On the Irish Setter, Eric Parker wrote in his Shooting Days of 1918: “When first he sees the red setter go out gaily ranging, when the easy gait through the heather suddenly checks and stiffens, and a friendly arm – after how breathless an interval! – waves the dog forward and inward; there is gathered for him then into that short space the sum and the meaning complete of shooting as a sport of the hills for boys and men. He is out, free and a hunter…” He has captured the essence of bird-dog use and its passing is sad. But the working stock has declined appreciably. Away from the working stock, far too many of our native bird dogs are criticized for being too slab-sided, too weak in the hindquarters and all too often have upright shoulders and short upper arms. Of course, any and every breed receives criticism and this is hardly new. A correspondent to The Kennel Gazette of February 1890 wrote: “I have read Mr Serjeantson’s remarks on Irish Red Setters in your number for this month, and probably he may be pleased to learn that very many of the most experienced breeders in Ireland fully endorse his opinions, that latterly breeders of the Irish Red Setter for show purposes have sacrificed the grand old powerful big-boned animal for the sake of beauty, chiefly in colour, coat, and feathering, and have thereby produced the many present-day weedy successors of the old type- no doubt beautiful, but weedy in bone.”

On the Gordon Setter, the impressive Edwardian dog-writer James Watson, in his invaluable The Book of the Dog, wrote: “In using the name of Gordon setter for the black and tan variety we do so because it has become universal, though it is undoubtedly a misnomer, if it is meant to specify that the breed so named originated with the Duke of Gordon, or was alone and specially fostered by him. That this nobleman, who died shortly prior to the oft-mentioned sale of dogs in 1836, by no means confined himself to a special colour is an entirely wrong idea.” A forthright statement supported by plenty of evidence.

In his wide-ranging A Survey of Early Setters of 1985, an admirable piece of research, Gilbert Leighton-Boyce refers to an account of a visit to the Duke of Gordon’s kennel that took place in 1862. This read: ”…we beguiled the way by a chat with Jubb, the head keeper, whose seven-and-thirty black-and-white tans were spreading themselves…Originally the Gordon setters were all black and tan…Now all the setters in the castle kennel are entirely black and white, with a little tan on the toes, muzzle, root of the tail, and round the eyes. The Duke of Gordon liked it, as it was both gayer and not so difficult to back on the hillside as the dark-coloured…The composite colour was produced by using black-and-tan dogs to black-and-white bitches…”

Against that background the setter colours of today look rather impoverished; we have become transfixed by the aura of the pedigree. Not so the Duke of Gordon who was described as "not a man to confine himself to shades and fancies"; he once used a Spitz-wolf cross on deer courses. His black-and-whites may have been a result of using a brace of English Setters given to him by Captain Robert Barclay of Urie. In New Zealand, a litter of black and tans was once produced from an unplanned mating of a Blue Belton English to an Irish Setter bitch. The Duke would not have approved the setters named after him needing to possess the now mandatory black and tan jacket of the breed. Not so too the founder of the modern setter, Laverack, who wrote that a change of colour was as good as a change of blood. The advent of dog shows has brought an absurd conformity, restricted breeding programmes to the diktat of the breed standard's stipulations and led to mis-marked but otherwise high quality dogs being lost from the gene pool. Bob Truman’s outstanding black and white Gordon Setter, Freebirch Vincent, so successful as a working dog, would never win in the show ring, despite his excellent conformation and field prowess.

Our Kennel Club’s breed standard for the Gordon Setter makes the following stipulation on coat colour, apart from setting out the black and tan markings: ‘Very small white spot on chest permissible. No other colour permissible’. The Duke must be turning in his grave! Such needless and destructive restrictions can undermine a breed, especially when potentially outstanding specimens are consigned to the bucket at birth on flimsy colour grounds alone. When the last of our native setter breeds goes, so too will go an important and stylish aspect of our sporting world and the gundog world certainly will be an impoverished place as a direct result. These handsome dogs were responsible for 'setting the style' in game shooting and we lose much on their demise.