662 Behaving like a Dog

BEHAVING LIKE A DOG

by David Hancock

You have little chance in the busy world of today of finding a newly published book on dogs entitled: "Dogs: Their Points, Whims, Instincts, and Peculiarities. With a Retrospection of Dog Shows". The title alone dates this book, which was edited by Henry Webb. The Rev Charles Williams was responsible for another book, about the same time, entitled: "Dogs and Their Ways; Illustrated by Numerous Anecdotes Compiled From Authentic Sources". The sheer quaintness of such titles indicates a certain charm as well as a certain time in book publishing. The value of such books, to me, is that they tend to record highly individual almost eccentric behaviour in dogs which adds to our knowledge of them.

You have little chance in the busy world of today of finding a newly published book on dogs entitled: "Dogs: Their Points, Whims, Instincts, and Peculiarities. With a Retrospection of Dog Shows". The title alone dates this book, which was edited by Henry Webb. The Rev Charles Williams was responsible for another book, about the same time, entitled: "Dogs and Their Ways; Illustrated by Numerous Anecdotes Compiled From Authentic Sources". The sheer quaintness of such titles indicates a certain charm as well as a certain time in book publishing. The value of such books, to me, is that they tend to record highly individual almost eccentric behaviour in dogs which adds to our knowledge of them.

In the first book, Webb recounts the story of a ferocious cat- hating dog, all but mortally wounded in a serious fight with a staghound, being saved by a resolute female passer-by's actions. This fierce usually unapproachable dog 'came to love her, often brought her the hares he killed, and, best favour of all to the old maid, considerately permitted her cat to live during his royal pleasure; but, if he met the cat abroad, he changed his direction, and inside, he never let his eyes rest upon her.' Very clever highly-trained scientists of today tell us that dog does not have the mental capacity for conscious thought in such an incident. I wonder. In the second book, Williams quotes Lord Carnarvon as saying: 'A dog is united by so many sympathies to the human race -his habits are so identical with ours -the love of his own species is so completely superseded by his love of man.. .' I doubt if the more matter-of-fact language of today could ever express such a sentiment so meaningfully.

A more recent account of the capricious behaviour of a Foxhound over a lady's hat would find no outlet nowadays but is still fascinating. A Foxhound, when puppy-walked by a lady hunt-follower, showed a distinct fondness for one of her hats, which was discouraged. One day, a whole year later, when this pup had joined his pack as an entered adult, it was in full cry and passing the lady who had reared him. Unfortunately she had fallen into a water-filled dyke and was clinging to tree roots with both hands; she was however wearing the very hat which the hound, as a puppy in her care, had so much coveted. The now- adult passing hound, without slowing down, galloped over to the vulnerable hat-owner, reached triumphantly down and deftly lifted the hat from her head, to rejoin the frantic pace of the hunt, hat in mouth.

Call it brazen opportunism or an incident waiting to happen, it is still a remarkable feat of scenting at speed for any dog to achieve. The hound clearly only had a second to identify its favoured hat and to decide to steal it. To achieve this clarity of thought whilst flat out in the chase is simply astonishing. The hound's scent-memory, fortified by an instant recall system, enabled such a weirdly-calculated feat to be conducted; it is remarkable, and worthy of note when dogs are being considered for wider employment, Foxhounds especially. Not perhaps as hat-collectors but as fast scent-collectors. The whims and peculiarities of dogs certainly beguile us.

But what about the behaviour, the whims and peculiarities of dog's lord and master -man? In one century the ears of the dog can be cropped without outcry, in the next it's forbidden. Now a dog's ears can be cropped in some countries but not others. Similarly with tails; at one time little thought was given to tail-docking, then, especially for certain vets it was made into a big issue. These vets however belong to a profession which lightly advocates castration of male dogs, allegedly to 'improve' their temperament. So they can't be against the mutilation of dogs in principle. It makes the behaviour of an errant Foxhound rather less eccentric.

A few years ago a lady breeder expressed strong views on ear- cropping in her breed yet bred from stock which carried primary glaucoma. I suspect that her dogs would prefer cropped ears, however painfully executed -and it is, to blindness and an early death. Perhaps kennel-blindness should be bred out! Far too many breeders of pure-bred dogs will happily sign a petition to stop ear-cropping or tail-docking but will not take the time to complete a health survey form for their breed and then sign it. In England the Kennel Club has long been the easy target for the moaning members of breed clubs, at times rightly so. But I am full of praise for the KC's increasing efforts to attempt to survey the genetic health of pure breeds registered with them. Support for their attempts to do so is, sadly, poor.

In 1999, the KC sent out a survey to create a database of existing breed club health committees, to indicate the need for guidelines for clubs to follow and, importantly, to focus attention on health issues by listing current health priorities. The survey went to 700 registered clubs and societies. 460 responded, a rate of 66%, representing 77% of the 148 breeds the KC then recognised. But whilst at that time 88 breeds had some form of health surveillance, only 13% had a health committee, only 27% had a health/welfare coordinator and only around 20% of all breed clubs had some form of health surveillance in place. That surely had to and did change.

Some might observe that this initiative by the KC should have happened two decades earlier. Better late than never, would be my observation. But should the health of a breed be at the mercy of the whims and peculiarities of breed club officials? In accepting their appointments the latter immediately assume the role of breed custodians. The whims and peculiarities of dogs can be endearing and tell you much about their inner selves. There is nothing endearing about a breed club which doesn't care about the health of its dogs. Their attitude tells you a great deal about the 'inner selves' of breed officials. It is to me quite shocking that first of all, breed clubs should remain so indifferent to the state of health of their breed and secondly, that this situation is unlikely to improve. If those who claim to love their breed have little interest in improving the health of their breed, perhaps the matter should be taken out of their hands. A couple of years ago, I wrote in an article that every breed club should, as a pre-condition of registration, have to have both a health coordinator backed by a committee and an up-and- running breed rescue scheme. My instinct is always against over-regulation, but when dogs' health is demoted to an unacceptably low priority or given no priority at all, then I believe a resort to regulation is imperative. If breed club officials don't care about the health of their breed, then they should be made to, or face a failure to obtain KC registration. This isn't a matter where human whim can be left to indulge itself; it is a crucial issue for the future of a number of breeds. The pursuit of better health and a healthier genotype should be conducted with all the determination, acuity and opportunism of our hat-stealing Foxhound. We must take our chance before it is too late. If a whim is a sudden fancy then a sudden fancy to safeguard the best long term interests of our purebred dogs is desperately needed. But why desperately needed?

Is it true that 70% of collies have CEA? Do 50% of Cavaliers have heart trouble? Are 70% of Dobermanns carriers of Von Willebrand's? Will all small white breeds one day suffer from 'white dog tremor syndrome'? Why do all three varieties of Poodle have a genetic predisposition to idiopathic epilepsy? Is the problem of cataracts increasing in Australian Shepherds? What are the underlying causes of calcium oxalate uroliths in five different Toy breeds? Is Cushing's Disease becoming more prevalent in older Boston Terriers? Is overgrowth of footpads going to become a future problem in Kerry Blue Terriers? Are there any Boxers free of heart murmurs? Veterinary surgeons acknowledge that there is no official way to discover which diseases are prevalent in companion animals. If that is so, and breed clubs don't care, how on earth can we fight disease in the domestic dog? Keep in mind Lord Carnarvon's view that dog's love of man supersedes that of itself? What about our national much-quoted love of dogs? Is it just idle boasting or vain human aspiration? There are of course breed clubs which have made laudable efforts to combat problems in their breeds. The quick and decisive action of the Alaskan Malamute Club of America reduced the rate of dwarfism in their breed to zero per cent. The water storage problem in the Portuguese Water Dog in America was successfully overcome. Some individuals in the Boxer world here have worked really hard to combat axonopathy in the breed. Keeshond breeders here tried hard to fight epilepsy in their breed. The Golden Retriever Breed Council in Britain has a commendable awareness of inheritable problems in their breed. The Kennel Club will not now allow carriers of CLAD to be registered- a hugely significant precedent.

Insurance companies too can contribute data; of 2,500 claims for tumour treatments, Boxers and Dobermanns led the field. I'm not aware of any research into head gland disease found to be most frequent in Gordon Setters and Dachshunds, suggesting that the condition is hereditary. One study actually carried out in Sweden on cataracts in Westies, discovered that 49 of the 97 inter-related dogs studied were afflicted. 35% of the affected dogs were younger than 6 months. When I asked a Westie breeder at Crufts about this study he professed never to have heard of it. International cooperation is vital in this fight; every Westie in the world originated in Britain. Breeder awareness comes second only to breeder honesty.

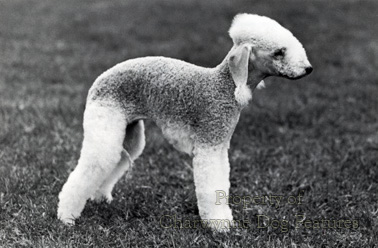

I salute the work of the Bedlington Terrier community in tackling t he copper toxicosis problem; this involved both the show and the working clubs, some achievement. The University of Utrecht was involved in this work, proving the absolute need for international collaboration. The Genetics Chairman of the Dandie Dinmont Terrier Club of America sent details of their health survey to UK breed fanciers; one of the most worrying findings was the incidence of hypothyroidism. I do hope that this ancient breed isn't going to be penalised by a lack of comparable research in Britain. The internet is going to be an important source of information exchange between breeders and scientists from now on. But I suspect that the answer lies more in the heart of man. Within every breed there is concealed knowledge about breed health, lines of flawed breeding and defects linked to certain kennels. There can be no moral justification for such concealment.

he copper toxicosis problem; this involved both the show and the working clubs, some achievement. The University of Utrecht was involved in this work, proving the absolute need for international collaboration. The Genetics Chairman of the Dandie Dinmont Terrier Club of America sent details of their health survey to UK breed fanciers; one of the most worrying findings was the incidence of hypothyroidism. I do hope that this ancient breed isn't going to be penalised by a lack of comparable research in Britain. The internet is going to be an important source of information exchange between breeders and scientists from now on. But I suspect that the answer lies more in the heart of man. Within every breed there is concealed knowledge about breed health, lines of flawed breeding and defects linked to certain kennels. There can be no moral justification for such concealment.

The Kennel Club is at last trying to lead the way over combating dog's inherited ailments or predispositions to conditions. The Animal Health Trust works nobly. But I suspect that in every breed of purebred dog there are inheritable flaws being concealed, hushed up or just plain ignored. This is wholly irresponsible and morally reprehensible. The reporting, recording and collating of data on dogs' genetic problems must become the leading priority of every breed club permitted to be registered with any registry anywhere. It shouldn't require legislation to force breed clubs to serve their own breed more honourably but if it does, then so be it. If a breed club seeks registration with a kennel club, so that it can run activities then wider responsibilities must surely accompany such a right.

The whims and peculiarities of dogs are quaint; leaving the improvement of dogs' genetic health to man's whim is far from quaint and definitely peculiar. Breeding dogs to an unhealthy design is already receiving attention in the European legislature; breeding dogs likely to inherit disabling faults is a matter of individual conscience and collective will within breeds themselves. But as research stumbles forward unaided by clubs, I do hope that public moral outrage alone will not, in an age of animal fanaticism, shame those breeders of purebred dogs who are more wallet-led than conscience-directed. It is the task of every dog-lover to serve these admirable creatures who give us precedence when allocating their love, which really does 'supersede' their love of themselves. It's time that our love for dogs superseded that for our own bank balances. We need to raise our moral standards; we need an aspiration - perhaps to behave like dogs. They so often shame us.