657 Boar Lurchers

THE BOAR LURCHER

by David Hancock

Big game hunting became almost an obsession with some Victorian sportsmen, with some wealthy hunters spending enormous sums and huge amounts of time at this pastime. Sir Samuel Baker describes in his book 'The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon' the use of various dogs in big game hunting. He took a pack of thoroughbred Foxhounds there with him from England, but only one survived a few months hunting in Ceylon. He favoured, for elk-hunting, a cross between the Foxhound and the Bloodhound, using fifteen couple, supported by lurchers.

Baker stated that the great enemy of any pack was the leopard, which would leap down on stray or isolated hounds and kill them. Baker was fond of 'deer-coursing', the pursuit of axis or spotted deer using Greyhound and horse. He used pure Greyhounds, "of great size, wonderful speed and great courage." A buck could weigh 250lbs and would turn and charge its pursuers, unlike the elk which stood at bay. With some sadness he wrote that "the end of nearly every good seizer is being killed by a boar. The better the dog the more likely he is to be killed, as he will be the first to lead the attack, and in thick jungle he has no chance of escaping from a wound." The boar-lurcher has never received the recognition it merits.

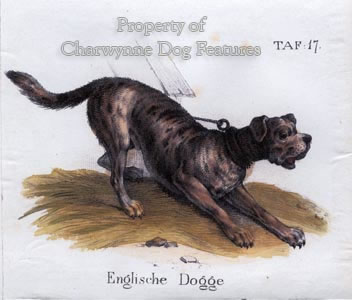

It would be good to see appropriate recognition for the boar-lurchers or hunting mastiffs, whether described as docgas, bandogges, seizers, holding dogs, pinning dogs, perro de presas, filas, bullenbeissers or leibhunde. They should at least be respected for their past bravery and bred to the design of their ancestors. A big game hunting breed like the Mastiff of England seems prized nowadays solely for its weight and size. The Englische Dogge (dogge meaning mastiff) was once famous throughout central Europe as a hunting mastiff par excellence. It is a fact that, in the boar-hunting field in central Europe in the period 1500 to 1800, many more catch-dogs were killed than the boars being hunted. In those days there was a saying in what is now Germany that if you wanted boars' heads you had to sacrifice dogs' heads.

Many types of dog have been used in the boarhunt, with only one modern breed, the Great Dane or German Mastiff, directly inheriting the boarhound mantle. Hounds of the pack were often regarded as too precious to be risked in the final moments of the boarhunt, so more coarsely-bred dogs were used 'at the kill', being considered expendable. These were variously described as catch-dogs, bandogges, alauntes and seizers. They were recklessly brave, remarkably agile, extraordinarily determined and admirably athletic. A better name for them would be 'boar-lurchers'; they were never intended to be a breed, they were never uniformly bred and nearly always owned by the lower classes, who were sometimes paid or rewarded for doing so, as a contribution to the hunt.

In England, in the reign of Henry the Second, the wild boar was hunted with hounds and spears in many wooded areas, from the Forest of Dean to Warwickshire and beyond. King James hunted the boar at Windsor, this being described as "a more dangerous amusement than it was likely he could find any pleasure in". Turbervile writing in the late 16th century, recorded that hounds accustomed to running the boar were spoiled for game of scent less strong. They were alleged to be less inclined to stoop to the scent of deer or hare and disinclined to pursue a swifter quarry which did not turn to bay when out of breath. The East India Company introduced hunting dogs from England into India in 1615; on one occasion a mastiff from England shaming "the Persian dogs" at a boar kill.

In central Europe there were once huge dogs used in the boar hunts of the great forests of what is now Germany, western Poland and the Czech Republic. They were known as 'hatzruden' (literally big hunting dogs), huge rough-haired crossbred dogs, supplied to the various courts by peasants. They were the "expendable" dogs of the boar hunt, used at the kill. The nobility however bred the smooth-coated 'sauruden' (boar hounds), and 'saupacker' (literally, member of a pack used for hunting wild boar). The 'saufanger' (boar seizer) was the catch-dog or hunting mastiff.

The 'sauruden' were the equivalent, in the late 18th century, of the hunting alaunts of the 15th century, with the Bullmastiff being the modern equivalent of the "alaunts of the butcheries". The specialist 'leibhund', literally 'body-dog', was the catch-dog used to close with the boar and seize it. I believe it is perfectly reasonable to regard the modern breed called the Great Dane (in English-speaking countries) or Deutsche Dogge (German mastiff) as the inheritor of the saurude or boar hound mantle.

The true boar hound, a hound of the chase or chien courant, as opposed to a huge crossbred dog once used at the killing of the boar, deserves our respect. Such a hound was required to pursue and run down one of the most dangerous quarries in the hunting field. It needed to be a canine athlete, have a good nose, great determination and yet not be too hot-blooded. Both the Fila Brasileiro and the Dogo Argentino have been used in the boar hunt in South America. American Bulldogs are still used as catch-dogs on feral pig in the USA, with Bullmastiff crosses being favoured in New Zealand.

In our modern so-called more tolerant society, such powerful determined hunting dogs are stigmatized and even banned in some allegedly liberal countries. Paradoxically the most wide-ranging ban has been imposed in a country whose citizens have carried out the worst atrocities in modern history. These are not happy times for hunting dogs bred by man to be determined, strong and recklessly brave. Sadly, they are also irreplaceable. Prized for several millennia for their dash and bravery, powerful sporting dogs are now under suspicion just because they are powerful. We may not want strapping courageous dogs to pull down big game for us any more but they are part of our sporting heritage and deserve our support. We never lacked support from them.

The great forests of central Europe provided endless opportunities for hunting. In the 19th century the pursuit of wild animals with hounds was conducted on a vast scale. In France there were over 350 packs of hounds. In 1890 the Czar of Russia organised a grand fourteen day hunt in which his party killed 42 European bison, 36 elk and 138 wild boar. In many of these hunts, scenthounds, sighthounds, running mastiffs or par force hounds (the true gazehounds) and hunting mastiffs (often held on the leash until needed at the kill and called 'bandogges' by the Saxons) were used in the same hunt.

The ancient Greeks, Gaston Phoebus in the 14th century, the Bavarians in the 17th century and the Czars in the 19th century used hunting dogs of different types in unison according to function. Sighthounds, scenthounds and hunting mastiffs were used together and not hunted separately, unlike our more specialist packs. Boarhounds could therefore be the loose term to describe all hounds on a boar hunt, whatever their function in the chase and kill. Casual researchers can therefore look at a painting of a boar hunt or read accounts of one and jump to all sorts of false conclusions about what boarhounds could look like in past times.

The invention of firearms brought not just dramatic advantages to hunter-sportsmen but a substantially reduced risk to their lives. This very much lessened their dependence, in some forms of hunting, on determined courageous dogs. We live in times when powerful dogs brave enough to tackle boar, bull and bison are banned in some countries, not because of any current misdeeds, but purely because of their past as a type of dog. In modern times too a dog that can singlehandedly catch a hare is valued less than a dog that can only retrieve a dead rabbit. Until the writings of Phil Drabble and then Brian Plummer redressed the situation, whole libraries were devoted to dogs only capable of retrieving dead game whilst books on lurchers and catch-dogs were as rare as a sighthound in jungle country.

A number of enthusiasts have and still are attempting to recreate the medieval type known as Alaunts, of which there were three main types of Alaunts: one resembled a strong-headed sighthound, another the Great Dane and a third the classic 'butchers' or holding dog, rather like the Bullmastiff. To seek to recreate a breed called the Alaunt involves the production of a type spanning say the Greyhound, the Cane Corso and the Bulldog; that would be some achievement. It would be just as difficult to restore the bandogge as a distinct breed and there is comparable confusion about this type. Even as diligent an author as Robert Leighton, in Edwardian times, took the view that the name bandogge or tie-dog referred to a secured guard dog. Sadly most of the revered Victorian writers on dogs cribbed from each other and in so doing cemented myths through sheer repetition. The words of Barnabe Googe in the 16th century linked the word bandogge with a tied-up house dog and, no doubt such a formidable dog made an effective protector of the house---and needed tying up!

Rather than a tethered yard-dog, I believe there is ample evidence to indicate that the bandogge was a seizing dog, leashed during the hunt, until required as a catch-dog, to grip or hold big game which has been chased to near-exhaustion by the running mastiffs, of Great Dane type. This is a time-honoured way of hunting big game with powerful hounds, as the Assyrian bas-relief demonstrates. The 'band' or tie retains the savage dogs until the moment they are needed to risk their lives at the behest of man. There are countless portrayals of this in medieval paintings and engravings. There is an old English ballad of around 1610 which includes the lines: "Half a hundred good band-dogs, Came running over the lee." There is little indication of solitary tied-up yard-dogs in those words.

The Alaunts were the dogs of the Alans. The Alans were astounding horsemen, so rated as to provide the cavalry for the Roman legions. In a well known inscription, found at Apta on the Durance, the Emperor Hadrian praises and commemorates his 'Borysthenes Alanus Caesareus Veredus' that 'flew' with him over swamps and hills in Tuscany, as he hunted the wild boar. The Romans hunted the wild boar with hunting mastiffs; the Alans would have provided hunting mastiffs as well as horses, their renowned Alaunts. The governors of Milan were once commended 'because...there have sprung up in our region noble Destriers (the war horses of medieval knights) which are held in high estimation. They also reared Alanian dogs of high stature and wonderful courage.' Chaucer did of course refer to 'Alauns' as big as steers; the type was evidently acknowledged here then.

As the cavalry for the Roman legions, the Alans have left their mark in Britain. The Avon in Hampshire was once called the Alaun, as was the Alne in Northumberland. Allaway in Scotland comes from this source too. In his very informative The Master of Game of 1410, the renowned hunter Gaston de Foix's words on French dogs are reworked by Edward, second Duke of York. He describes the Alaunt as a hound 'better shaped and stronger for to do harm than any other beast'; he made a distinction between mastiffs and Alaunts. He regarded the latter as seizing dogs, the former as big running mastiffs, for use in the chase. De Foix was the greatest hunter of his time, maintaining a kennel of over a thousand sporting dogs. He would not have blurred mastiffs with Alaunts, he used them in different ways. They had different functions.

In England, the name 'mastiff' wasn't in common use until quite a late date, the end of the 18th century; Osbaldiston, in his famous dictionary, utilises the long-established word of Saxon origin 'bandogge'. Scholars are not always reliable sources of information on breeds or types of dog. Sherwood, in his dictionary, defines a mastiff as an alan. Cotgrave, in his his pastime. Sir Samuel Baker describes in his book 'The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon' the use of various dogs in big game hunting. He took a pack of thoroughbred Foxhounds there with him from England, but only one survived a few months hunting in Ceylon. He favoured, for elk-hunting, a cross between the Foxhound and the Bloodhound, using fifteen couple, supported by lurchers.

Baker stated that the great enemy of any pack was the leopard, which would leap down on stray or isolated hounds and kill them. Baker was fond of 'deer-coursing', the pursuit of axis or spotted deer using Greyhound and horse. He used pure Greyhounds, "of great size, wonderful speed and great courage." A buck could weigh 250lbs and would turn and charge its pursuers, unlike the elk which stood at bay. With some sadness he wrote that "the end of nearly every good seizer is being killed by a boar. The better the dog the more likely he is to be killed, as he will be the first to lead the attack, and in thick jungle he has no chance of escaping from a wound." The boar-lurcher has never received the recognition it merits.