651 Changing the Past

CHANGING THE PAST

by David Hancock

When studying the changes in breeds of dog, changes often introduced by breeders to suit their interpretation of the breed's design, it is always worth asking a number of key questions. Were the changes actually necessary? Is the particular breed more handsome as a result? Were the changes made to suit the breed or its breeders? In a recent interview in the British dog press, a well-known dog show judge attempted to explain all pure-bred dog breeding as being justified by the mere pursuit of canine beauty. But can the pursuit of beauty truly justify every breed configuration? Have show breeders actually made their various breeds more beautiful?

When studying the changes in breeds of dog, changes often introduced by breeders to suit their interpretation of the breed's design, it is always worth asking a number of key questions. Were the changes actually necessary? Is the particular breed more handsome as a result? Were the changes made to suit the breed or its breeders? In a recent interview in the British dog press, a well-known dog show judge attempted to explain all pure-bred dog breeding as being justified by the mere pursuit of canine beauty. But can the pursuit of beauty truly justify every breed configuration? Have show breeders actually made their various breeds more beautiful?

It is worth looking at say a breed or two from each of the KC groups in the show ring to verify or dismiss the case for the show ring as a beauty contest. Take the Bull Terrier from the Terrier Group, the Basset Hound and the Bloodhound from the Hound Group, the Bulldog from Utility, the Mastiff from the Working, the Rough Collie from Pastoral, the Clumber Spaniel from the Gundog and the Pomeranian from the Toy Group. Put aside the health and welfare aspects of their breeding; overlook the need for every breed to pay homage to the function for which it was designed. Let's just concentrate on beauty, acknowledging the 'eye of the beholder' caveat. In each of these long-established breeds, are today's dogs actually enhancing or even perpetuating 'the beauty of the breed'?

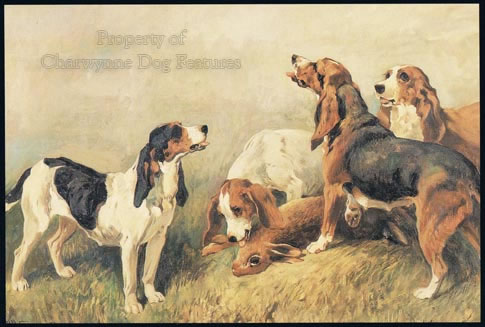

Our dictionaries tell us that beauty is a pleasing combination of qualities, such as shape, proportion and colour, which delight the sight, please one or more of the senses or the mind, a particular grace or excellence. Aesthetic appeal will always be subjective, but beauty of form can still be universally acknowledged, the camera or the canvas often conveying this. It's interesting and of value to compare the depictions of breeds in past times to the specimens of those breeds we see in our show rings today. The pictorial record of our breeds of dog is immensely important; it illustrates the historic mould for each breed and can serve to establish breed type, especially when disloyal factions try to lead a breed away from true type to 'their type'.

A casual new visitor to dog shows will not always be aware that the early specimens were in many breeds markedly different from the type now being sought by breeders. The Bull Terrier hasn't always featured a sheep's head; the Bulldog hasn't always been muzzleless; the Mastiff has not always been so heavy and ponderous or the Pomeranian so tiny. The Bloodhound was once tighter in eyes, mouth and skin and the Basset Hound leggier. The Rough Collie hasn't always been so h eavy-coated or so Borzoi-headed. Have such changes made each of these breeds more beautiful? Have they been so gradual that fanciers haven't noticed until it's too late? However changes occur, it is simply not honest to claim at today's show benches, when asked why such and such a breed looks the way it does, to answer that it's because it always has.

eavy-coated or so Borzoi-headed. Have such changes made each of these breeds more beautiful? Have they been so gradual that fanciers haven't noticed until it's too late? However changes occur, it is simply not honest to claim at today's show benches, when asked why such and such a breed looks the way it does, to answer that it's because it always has.

In many bygone depictions the Mastiff is portrayed as a very good-looking dog indeed: symmetrical, active, athletic and neither heavy-headed nor loose-lipped. Increasingly, today's specimens are looking more and more like the Alpine Mastiff, which resembled a fawn smooth St Bernard. The Mastiff was re-created in the 19th century using Great Dane, Alpine and Tibetan Mastiff blood, all of course from overseas. It is absurd to describe the contemporary breed of Mastiff as being the same dog as the one bearing that title two hundred years ago in England or to prize its Engl ish heritage. Few would describe today's breed as beautiful but there was a majestic beauty about the big strapping Mastiffs of the early 19th century and before that. The longer coats cropping up in the breed and the much longer ears defy the breed standard but don't seem to deter exhibitors or even judges in today's rings. Outcrossing to alien breeds to achieve great size brings in other physical attributes too. It certainly hasn't brought good looks to the contemporary breed of Mastiff.

ish heritage. Few would describe today's breed as beautiful but there was a majestic beauty about the big strapping Mastiffs of the early 19th century and before that. The longer coats cropping up in the breed and the much longer ears defy the breed standard but don't seem to deter exhibitors or even judges in today's rings. Outcrossing to alien breeds to achieve great size brings in other physical attributes too. It certainly hasn't brought good looks to the contemporary breed of Mastiff.

The Bulldog is rarely described as a beautiful breed. But my purpose is not to establish whether it is or it isn't, but to ascertain whether the show ring has increased its aesthetic appeal. Before the Pug cross, the Bulldog was, if its depiction then is at all accurate, more symmetrical, more athletic, better proportioned and more pleasing to the eye. 20th century books on the breed omit to mention this outcross, but half a dozen reputable Victorian or Edwardian writers on dogs testify to it taking place. The legacy of Pug blood in the Bulldog is easy to spot: the muzzle-less skull, the wrinkle, the beauty spots, the fawn smut colouration and the trace or darker spinal marking. Outcrosses usually bring long-lasting slow-to-surface features. Thirty years ago a distinguished Pug breeder told me that the problems of obtaining the correct ear carriage in her breed came from the 'unwise introduction of Bulldog blood in the 19th century'. From the pictorial evidence it does not look as though the show ring has improved the Bulldog's beauty.