599 Flushed with Success

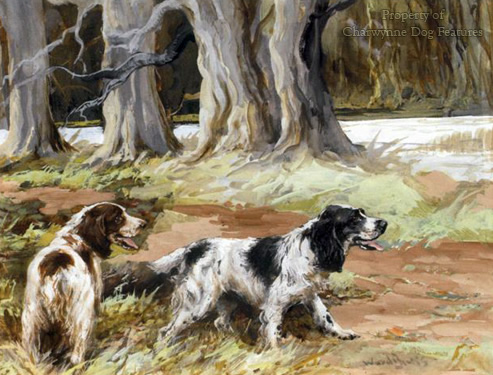

FLUSHED WITH SUCCESS

by David Hancock

"The spaniel, in my opinion, is the most difficult of all dogs to break in a scientific manner, and this for one reason only, simply because his work takes him very frequently out of your sight in thick cover...his duty being for the most part to 'roust out' his quarry..."

Those words from The Scientific Education of Dogs for the Gun, by 'H.H.', of 1920, give an instant impression of the time-honoured role and difficulty of achieving steadiness in spaniels. The late Brian Plummer would no doubt have crossed a spaniel with a working sheepdog to obtain that measure of human control needed! I have long been surprised at how tolerant of a lack of steadiness many gundog men are of their spaniels. Half a millennium ago, in his informative The Master of Game, de Foix was writing: '...a spaniel, if he see geese or kine, or horses, or hens, or oxen or other beasts, he will run anon and begin to bark at them', going on to accuse them of 'so many other evil habits'.

General Hutchinson, in his valuable Dog Breaking of 1909, wrote that 'even good spaniels, however well bred, if they have not had great experience, generally road too fast. Undeniably they are difficult animals to educate...' The late Keith Erlandson once wrote that 'a good Springer should have the qualities of the Spanish fighting bull and the Zulu warrior', some combination! But he did describe Cockers as 'inveterate belly crawlers and the sight of one pulling himself forward by his elbows, hind legs stretched straight out behind him causes me such amusement, with a resulting breakdown in concentration...' Sounds like a dog literally pushing its luck to me! But it does show the difference in self-control between an eager spaniel and say a Pointer frozen on point or a setter transfixed on set.

When judging working tests for spaniels on the country estate I once managed, I was always struck by the variety of temperaments on display. There were two main extremes: those eager, usually frenetically over-eager, to race forward head-up and allow instinct to triumph over training and those anxious to locate ground-scent first. It was not unusual to find spaniels too headstrong, much too led by their noses, deaf to their handlers' commands. At that time, I had two working sheepdogs, one a quite gifted setter, the other a quite brilliant flushing dog. I kept promising myself that one day I would take them to a working test event for gundogs and let them demonstrate their skills. But the best flushing spaniels I have seen were the Field Spaniels of the late Clive Rowlands, then a part-time gamekeeper on a Powys estate. From the famous Rhiwlas line, passed on by Jack Tannent, no thickness of cover daunted them, they were usually out of sight but always under voice control, like radio-operated little tanks.

In his The Sporting Dog of 1904, the American writer Joseph Graham wrote: 'Bolting or ranging beyond control of the handler is another of those faults of which superficial critics make much, but which, in nine cases out of ten, is readily controlled. This is a fault of overboldness...' He favoured a dog that 'kept the air full of birds', not every shootingman's preference. His fellow-countryman, Carl P Wood, in his Sporting Dogs of 1985, Gun Digest, wrote: 'Cocker Spaniels are excitable and emotional and should be handled with sensitivity and gentleness during training. They seem to know immediately when play stops and the boss gets serious. An act or motion that would not matter at all in play or roughhousing with a Cocker, if done at a 'serious' time, will cause emotional difficulty with many Cockers.' This is a subtle point, a perceptive one, but innate hot-headedness, allied to great sensitivity, in any breed, really tests the trainer, despite being rooted in an eagerness to perform.

In his undervalued Gundog Sense and Sensibility, Wilson Stephens has written: 'Every bright gundog knows, or thinks it knows, when it is out of range of authority. The man who can undermine its assurance in that regard has gone a long way to establishing his own infallibility and thus perpetuating the dog's respect.' He went on to advise that the dog needs convincing that its human partner is not a conveniently remote and relatively immobile figure, incapable of action outside a limited radius. He recommended the use of missiles, not as weapons of punishment but as a reminder that the handler was still in touch. I've never tried that, preferring to seek fail-safe methods of maintaining an invisible line between me and my dog; I like my dogs to look back towards me from time to time or at least, stop and listen for commands.

Wilson Stephens also points out that the canine brain tires before the canine body does, and so mental stamina in a flushing dog is important. Running riot can mean running mentally tired, with the working zeal outlasting the trained brain. Maintaining control over a tiring dog needs training in this regard. A dog with its energy flagging and its brain switched off is more likely to flush a covey out of shot. I have heard of cases in which a soft-mouthed spaniel became a hard-mouthed spaniel when it was becoming seriously overtired. I have yet to hear of a tired spaniel taking a self-imposed rest! And we all know to our cost the penalties of allowing a young child to become seriously overtired!

One youngster not overtired was the one I saw working his young spaniel on a thick hedgerow recently. He was only about 13 years old and totally absorbed in his task of teaching an eager spaniel to hunt hedges, this one a dense matted mass of mixed hawthorn, blackthorn, bramble and Scotch thistle. Not for him the boredom of urban street corners or the necessity of music-playing earphones or even that modern umbilical the mobile phone, or ear-dummy, as my farmer-neighbour calls them. It was a heartening sight, a wholly-committed young handler with an entirely dedicated young spaniel, a great team. Soon, the disturbed wildlife emerged, to the evident delight of the young gundog trainer, who had every right to look, shall we say, 'flushed with success'.