573 heelers nip'n'duck dogs

HEELERS: THE 'NIP 'N' DUCK'DOGS

by David Hancock

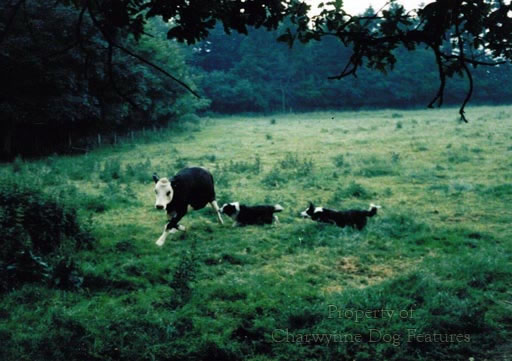

In 2006, there were over 500 Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgis registered with the Kennel Club, and just over 80 of the Cardiganshire variety. Originally classified as one breed, with only 10 being first registered in 1925, on their recognition, in 1950, there were well over 4,000 Pembrokes registered but only just under 170 of the Cardigan variety. Statistically it could be argued that the latter is maintaining its position better than the former, but it is the Cardigan which is listed as vulnerable. Patronage from the royal family led to the astonishing rise in popularity of the Pembroke dog and it has retained a steadfast bunch of fanciers. This Welsh heeler has kept its perky nature and natural assertiveness, but haslost some of the ruggedness of the earlier types. It takes courage and technique to drive cattle, a dog lacking agility being at a distinct disadvantage. Nipping a one ton bull then avoiding its resultant kick demands special qualities.

In 2006, there were over 500 Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgis registered with the Kennel Club, and just over 80 of the Cardiganshire variety. Originally classified as one breed, with only 10 being first registered in 1925, on their recognition, in 1950, there were well over 4,000 Pembrokes registered but only just under 170 of the Cardigan variety. Statistically it could be argued that the latter is maintaining its position better than the former, but it is the Cardigan which is listed as vulnerable. Patronage from the royal family led to the astonishing rise in popularity of the Pembroke dog and it has retained a steadfast bunch of fanciers. This Welsh heeler has kept its perky nature and natural assertiveness, but haslost some of the ruggedness of the earlier types. It takes courage and technique to drive cattle, a dog lacking agility being at a distinct disadvantage. Nipping a one ton bull then avoiding its resultant kick demands special qualities.

There has been speculation that the Welsh Corgis were taken to Wales by Viking invaders, with the Vallhund of Sweden identified as the source. I am not aware of the 'nip and duck' instincts of Scandinavian breeds, like the Vallhund, the Buhund or the Lapphund, but the Vallhund, whilst having its own distinct breed-type, is remarkably similar to the Pembroke Welsh Corgi. The Senjahund of Finmark is remarkably similar to our surviving English heeler, the Lancashire breed. Pastoral breeds accompanied migrants perhaps more than other types, rivalled only by hounds in value. It is easy to spot British influences in pastoral dogs used in former colonies. I have seen working sheepdogs here which could easily be taken for Australian Cattle Dogs or Australian Shepherds.

The Australian Cattle Dog is respected in many countries for its mental toughness, physical robustness and serious approach to work. This breed is believed to come from root stock of two Scottish blue merle working collies crossed with dingo, with Dalmatian and Kelpie blood introduced later. I see Bull Terrier features in the anatomies of many ACDs but am told that the outcross to the Bull Terrier was not considered a success and not favoured. The dingo blood is alleged to have produced the inclination to creep up behind cattle and bite them. But there has never been a shortage of British working collies with the instinct to get behind stock and nip it into compliance. I once owned two working sheepdogs which would nip the hocks of cattle as a herding tactic without any training to do so.

The origins of cattle dogs are often the subject of fierce debate, ludicrous speculation from so-called experts and remarkable ignorance about pastoral breeds. Dog writers in past times knew little of the humble pastoral breeds and this showed in their words. EC Ash, in his Practical Dog Book of 1930, wrote, on Corgis: "...they are a cross of Shetland Sheepdog with the Sealyham Terrier, and possibly Border Terrier..." But nine years later, was writing: "I am of the opinion...that the Welsh Corgi (Pembroke} is an Alsatian cross." About that time, Theo Marples was writing: "Probably the Welsh Sheepdog and the Bull Terrier had a hand in his making." Clifford Hubbard however, who made a comprehensive study of the Welsh breeds, linked the Pembroke variety with Flemish weavers who settled in the Haverfordwest area in the eleventh century. He considered that these migrants brought their Schipperke-like dogs with them to provide an essential ingredient in the emerging breed.

We tend to think of the Schipperke as a solid-black, tail-less dog, associated with Belgian barges and a breed title derived from 'little skipper'. But there are solid fawn and solid blue varieties, some with tails, and another school of thought linking them with dwarf Groenendaels, with a breed title derived from 'little shepherd'. This has some appeal for me; I see strong resemblances between the Schipperke, the Norwegian Buhund, the Iceland Farm Dog, the Norwegian Lundehund, the Norrbottenspets and the Vallhund of Sweden, the West Siberian Laika and the Corgis of Wales. It is always worth keeping in mind that useful dogs travelled with tribes or migrants across many centuries and across many borders.

But what about the only surviving English heeler breed, the Lancashire Heeler? With around 170 being registered annually this breed now appears to have been saved and have a sound future. This is very good news, firstly because we have lost too many of our native pastoral breeds, and, secondly because this is a breed well worth saving. A foot high, smooth-coated, black and tan or liver and tan, lively and perky by nature, they represent an ideal companion dog for many households. I do hope the show ring fanciers keep faith with the historic design of this breed and not produce, in time, Dachshund-like specimens with snipey jaws, bent legs and too low to ground a build. This is essentially a natural unexaggerated working breed, deserving to be conserved as just that.

As long as man needs beef and milk, he will need clever, brave dogs to support him. Butchers may no longer need strong-headed dogs to pin cattle at abattoirs or markets and the droves have long lost their role. But stockmen in many countries still need cattle dogs, dogs agile enough to dodge lashing hooves and sometimes heaving horns too, and brave enough to undertake the task in the first place. The Pembroke Corgi has retained its foxy head but is it becoming too short-legged? The early specimens were higher on the leg and most of them came from working stock. Is it ever wise to breed away from the design which function bestowed? A heeler with too long a back and a lack of the leg length to permit lightning reflex reaction when the cow kicks out, is not going to last long as a heeler. What is the rationale behind admiring a breed then changing its construction so that can no longer carry out its original function? Is that truly breed fancying or breed disloyalty?