557 THE HERDING BREEDS - The Scottish Contribution

THE HERDING BREEDS - The Scottish Contribution

by David Hancock

.jpg) Scotland has every reason to be proud of its contribution to the pastoral breeds of the world, Scottish pastoral dogs were developed in a harsh environment and for a demanding role. In the far north of the British Isles were the Kelpies of the Orkneys (now reborn in Australia), leggy dogs used to get grazing stock out to small islands at low tide, the bigger Scottish collies (with their rough, smooth and bearded variants) of the Highlands and what we now call Border Collies in the Lowlands and northernmost English counties. Shetland had its own type, smaller and more of a housedog. Cumberland too had its own sheepdog, some looking more like a German Shepherd Dog than its own collie relatives, others bearing almost the beardie coat. The original Border Collie type may have been forest sheepdogs (referred to as 'ramhunts' in some accounts) used to keep stock in clearings, constantly circling them to keep the flock together and deter predators. A pure strain of solid black or black and tan, sometimes chocolate or bronze coloured, collie was once favoured in Sutherland and Ross, with some experts linking them with Scandinavian herding dogs.

Scotland has every reason to be proud of its contribution to the pastoral breeds of the world, Scottish pastoral dogs were developed in a harsh environment and for a demanding role. In the far north of the British Isles were the Kelpies of the Orkneys (now reborn in Australia), leggy dogs used to get grazing stock out to small islands at low tide, the bigger Scottish collies (with their rough, smooth and bearded variants) of the Highlands and what we now call Border Collies in the Lowlands and northernmost English counties. Shetland had its own type, smaller and more of a housedog. Cumberland too had its own sheepdog, some looking more like a German Shepherd Dog than its own collie relatives, others bearing almost the beardie coat. The original Border Collie type may have been forest sheepdogs (referred to as 'ramhunts' in some accounts) used to keep stock in clearings, constantly circling them to keep the flock together and deter predators. A pure strain of solid black or black and tan, sometimes chocolate or bronze coloured, collie was once favoured in Sutherland and Ross, with some experts linking them with Scandinavian herding dogs.

The Collies of Scotland

“The English form of Sheepdog is, as far as I can find, described in earlier times than is the Scotch Collie; and I think it not improbable that the latter may be in part derived from the former and the Scotch Greyhound.” Those words from such a verbose chronicler of the dogs of the British Isles as Hugh Dalziel in his British Dogs of1888 reveals the widespread ignorance on the forms of pastoral dog in Britain in the 19th century. Although, to be fair, some of today’s Smooth Collies can be distinctly ‘greyhoundy’, certainly more than its sister breed. In his The Dogs of the British Islands of 1878, Stonehenge wrote, rather unhelpfully: “In Scotland and the north of England, as well as in Wales, a great variety of breeds is used for tending sheep, depending greatly on the locality in which they are employed, and on the kind of sheep adopted in it…In Wales there is certainly, as far as I know, no special breed of sheepdog, and the same may be said of the north of England, where, however, the colley (often improperly called Scotch), more or les pure, is employed by nearly half the shepherds of that district, the remainder resembling the type known by that name in many respects, but not all.”

Should the word ‘collie’ be restricted to Scottish sheepdogs, with the English ones, not called Border Collies but ‘Borders Sheepdogs’ after their use on the borders of the flock, rather than in the border country between England and Scotland? Writers in the 18th and 19th century used the word collie or colley very loosely. In his The Illustrated Book of the Dog of 1879, Vero Shaw was writing: “There has been an attempt made by one or two writers in The Live Stock Journal – which devotes no inconsiderable portion of its pages to canine matters – to designate this dog the Highland Collie, but there was an utter absence of any reasoning in justification of claiming for the Highlands of Scotland the honour of being the peculiar home of the Collie. We are rather disposed to think that the pastoral dales of the Lowlands of Scotland and the North of England have had more to do with breeding the dog to his present high state of perfection as a shepherd than the North Highlands…” He went on to stress that shepherds cared little for pedigree but bred entirely for performance.

In his Non-Sporting Dogs of 1905, Frank Townend Barton wrote: “Smooth-coated sheep-dogs are found in every county of Great Britain, and farmers and shepherds are very fond of them, many being splendid animals at their work. In breeding smooth-coated collies the chief difficulty presenting itself is in connection with the coat; so many specimens being mixtures. With careful selection and perseverance much more might have been done for the smooth coats. Certainly they have not the handsome appearance of their rough-coated brethren.” In his Our Dogs of 1907, Gordon Stables wrote: “The smooth-coated dog…although found in the Highlands, is a Lowland dog, with a Lowland coat and Lowland ways, and more at home among cattle than sheep.” Today, we have two separate breeds of Scottish Collie and not just distinguished by length of coat.

No Pure Origin

Those breed historians seeking a long and pure origin for the collies of Scotland would be wise to study the words of William Stephens on such dogs in The Kennel Encyclopaedia of 1907: “In the first Volume of the Stud Book, 78 ‘Sheep Dogs and Scotch Collies’ were registered up to the year 1874…Only 18 had pedigrees, and only three of these extended beyond sire and dam. There is no doubt that, some years ago, the Gordon Setter cross was introduced, the consequence of which was the production of black dogs with bright mahogany-tan markings, thin in coat, and possessing a Setter’s ‘Flag’, instead of pale tan markings, dense coat and thick brush.” Stephens went on to point out: “The great fault now met with is unduly exaggerated (Borzoi type of) head which is always accompanied by a stupid and vacant expression – quite unlike the intelligent expression of the true collie.” He would not have admired some of the Collie heads appearing in today’s show rings.

In her The Popular Collie of 1960, Margaret Osborne wrote:

“Unfortunately, far more recently than this date (i.e. the end of the eighteenth century, DH), infusions of different blood were introduced into the Collie, usually to satisfy a whim for a special point: the cross with the Gordon Setter was made to enrich the tan; with the Irish Setter in a misplaced attempt to enrich the sable; with the Borzoi to increase the length of head. As a result of the Irish Setter cross the words ‘setter red most objectionable’ came to be included in the earlier standards of the breed, and even today we all too often see the horrible results of the Borzoi cross in the receding-skulled, roman-nosed horrors which masquerade under the name of Collie.” It seems that Collie breeders would clandestinely outcross to achieve a change in a previous century, but forbid an outcross to remedy its after-effects in a succeeding century; an outcross to a different shorter-muzzled, broader-headed breed could so easily breed away from such an unwanted feature.

Critics of the Collie’s head and show ring alterations have long been at work. In his The Dog of 1933, James Dickie gave the view: ‘About sixty years ago the collie became a fashionable pet, and thereafter two new strains developed, the rough and the smooth show collies. It was then laid down that the head should be long, narrow and sharp, but not domed; since then dogs have been bred entirely without a stop and with extraordinarily narrow heads. The brain-pan, in fact, has been bred out of them, with the natural result that, compared with his working ancestor, the show collie is little better than a congenital idiot. The popularity of show collies is on the wane. The smooth variety was never common, and the rough variety, having been ‘perfected’ and become a fool in the process, is rapidly being superseded by dogs of less size and more brains.’ His prediction about popularity was, 30 years later, somewhat wide of the mark, but the severity of his words, with a forthrightness unlikely to be matched in dog books of today, do illustrate the depth of feeling over the changes in this breed brought about by show ring fanciers.

Damage by Promotion

In 1908, there were over 1,200 Rough Collies and 170 Smooth Collies registered with the KC; one hundred years later, in 2008, the figures were: 1,171 Roughs and 43 Smooths, the latter’s very survival being threatened. Twenty years earlier however, over 8,000 Roughs were registered, indicating the fickleness of the pedigree dog world and indeed the public response to the promotion on film of a breed. The ‘Lassie’ films gave enormous exposure to the Rough Collie; the Dulux paint commercial gave very damaging temporary exposure of the Old English Sheepdog, with rescue centres being overwhelmed by the breed in due course.

The pedigree dog world itself has not always been kind to the pastoral breeds, with the Rough Collie being a prime example. William Arkwright, the great working gundog expert, writing in The Kennel Gazette, July, 1888, had this to say: “…’fancies’, locust like, appear to have settled on the Collie, and, unless we can exterminate them, they will most assuredly exterminate the Collie. ‘Fanciers’ have recently determined that a Collie shall have an enormous head, an enormous coat, and enormous limbs, and that by these three ‘points’ shall he stand or fall in the judging ring; so they have commenced to graft on to the breed the jaw of an alligator, the coat of an Angora goat, and the clumsy bone of a St Bernard. A ‘cobby’ dog with short neck, straight thick shoulders, hollow back, and small straight tail, but graced with a very long snout and a very heavy jacket, is already common at our shows, and increases and multiplies…First of all, the Collie is intended for use, for definite work, and, as soon as we find ourselves breeding dogs that cannot gallop, jump, ‘rough it’, aye, and think too, we may be certain that, whatever he may have got hold of, it is not a sheepdog…”

In an editorial in the June 1890 issue of The Kennel Gazette the writer stated: ”…turn to sheepdogs: how many collies of the present day, who have won prizes, could clear a high hurdle or scamper over the backs of a flock of sheep to turn it?…the sheepdog is now a companion and not trained for work, many, we are afraid, would hardly be good for a long gallop, or could do more than run a mile or so behind a slow carriage.” Thirty years later, successful show Collies changed hands for extraordinary sums: Ch Squire of Tytton went to the USA for £1,250 and Ch Ormskirk Emerald was sold here for £1,300, huge sums at that time. The pedigree pastoral dog now had value a long way from the pastures and pens; in the show world such a dog could do no work yet be highly priced entirely on its appearance – and after its show career, its breeding potential. Inevitably, following very different criteria, showman and shepherd sought quite different attributes in their dogs. The shepherd didn’t have a need for a dog admired for its looks alone, he needed a worker, a gifted worker, almost another pair of hands and eyes.

Acquiring Sagacity

A passage from WH Pyne's 'The Costumes of Great Britain' of 1808 provides some insight into the life of a Highland shepherd: "The dog, by being constantly the companion of the Highland shepherd, acquires sagacity, far superior to what is common to the brute creation; appearing to comprehend all his master's commands...The shepherd, who is acquainted with the best spots for pasture, and who watches for prognostics of the weather, manages the flock accordingly, by the aid of the dog, who drives the sheep sometimes to the summit of a mountain, and at other times, to a particular spot upon its side, or into a deep glen, acting by the signals of his master; who stands on a conspicuous height, shouting his directions, and waving his crook, which the intelligent animal comprehends at a surprising distance."

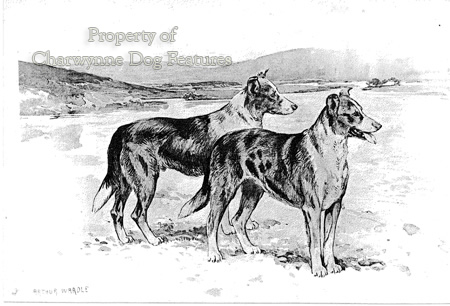

Pyne went on to describe the ability of the dog to single out individual sheep: "The shepherd at the time of collecting the flock in the evening for the purpose of counting it, fixes his crook in the ground, and stands a few paces therefrom: the dog drives the sheep between the crook and his master, who numbers them as they pass; but if a straggler goes on the outside, and mixes with those who have passed muster, the dog immediately pursues, singles him out, and brings him back." Against that background, it is not pleasing to give the opinion that the Rough and Smooth Collies and the Shetland Sheepdog did not survive the show interest in them of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with their working lives now ended. I have seen sheepdogs in the Lake District looking exactly like the depictions of Smooth Collies in the late 19th century. I have also seen miniature collies with smooth coats that have cropped up in working litters; if the Shetland Sheepdog had been named as the Miniature Collie, in two coats, it may have survived as a working sheepdog in the pastures. Breeds like the Poodle, the Pinscher and the Schnauzer have thrived in different sizes – it can be done!

The Sheepdog of the Shetland Isles

“In Orkney, on the pasture lands round the Scapa Flow, and especially on the island of Hoy, such miniature Collies were frequently to be seen a generation ago; but in later years they have been more closely associated with the Shetlands, where they were locally known as the Toonie Dog – name derived from their work of guarding the croft, or farm…North Sea fishermen and other visitors brought specimens of the breed to the mainland to keep as pets, and I have seen more than one in the seaports of East Anglia. It was from a Lowestoft fisherman that Mrs Feilden got a brood bitch whose puppies were afterwards shown at Crufts.”

From The Complete Book of the Dog by Robert Leightonof 1922.

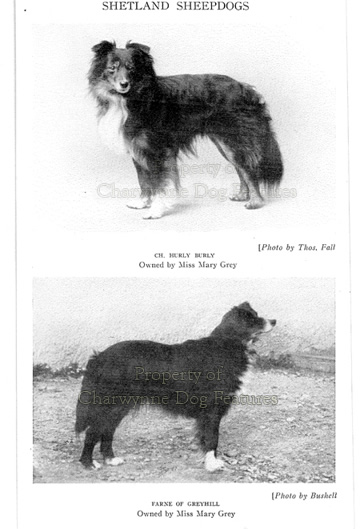

If you look at portrayals of the Sheltie in the show ring of a century ago, you could be forgiven for thinking it was then a quite different breed. Whilst this could be said of a number of breeds, in this one I very much prefer the 1913 specimens. If you look at photographs of Thynne’s Kilravock dogs, such as Laddie, a fine tricolour, the mainly white Cleopatra, Gipsy Love, a black and tan with a truly weatherproof coat, Eureka, a beautifully balanced bitch and Flora Modal, an excellent tricolour, you can see the sound foundation of any future breed. They all had strong wide-skulled heads, thick but not long coats and, unlike some of the chicken-boned contemporary dogs, ample bone and broad chests. From such stock could have come a really impressive breed. In due course, the Eltham Park kennel continued this type, but already, in their dogs, you could detect the heavier coat and lighter bone. They were much more collie-like than today’s dogs and why not? The Houghton Hill kennel became influential but led to over-use of this line, bringing a more refined head – continued in the Exford line. If the type exemplified in the 1920s, with Mary Grey’s Hurly Burly and Farne of Greyhill both fine examples, had been perpetuated then perhaps the drift towards being a Toy breed could have been averted. If this breed is to deserve its title of Sheepdog it has to justify that proud tag.

In his Dogs and I of 1928, sportsman and judge Harding Cox wrote: “The Shetland is a very small sheep dog, but it may well be too small! Already some of the prize winners are below the proper standard of inches and weight. They are not ‘Toy’ dogs, therefore any attempt to degrade them to such a level should be severely frowned upon and condemned. Judges take notice!” A dog looking more like a longer-backed Pomeranian, or ‘all fluff and no puff’ as one disillusioned Sheltie fancier put it to me, has no right to be named or considered as a sheepdog. In Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopaedia of 1934, the breed has these words on it: “…there are two distinct types of Shetland Sheepdog, but both are registered under the same name, a fact that has led to considerable difficulty and argument. The one variety is very like the Collie dog of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, before the days of registration, and the other is a miniature of the show Collie type…This rather unfortunate state of affairs has divided the breeders into two camps, and it is to be regretted that it did not at the same time divide the dogs…” Is this a discussion to be resumed if this breed is to establish lasting type?

Such criticism from ‘outside the breed’ will be resented but what are the breed experts, those appointed to judge future breeding stock saying, not so much on type but on quality? Here are some of their post-show critique comments: “I found just seven dogs in the entry with anything like the correct conformation…There is more to a Sheltie than a big coat and a pretty face…” (2011) “…breeders and exhibitors seem to be concentrating more on head, expression and fullness of coat to the detriment of construction…” (2011) “My main concern is that correct front angulation, as stated in the Standard, is now almost nonexistent. Judges have been bemoaning this in critiques for well over 30 years…” (2012). “I was disappointed to find so many steep upper arms and straight shoulders, in spite of so many critiques pointing this out from time to time, people don’t seem to be able to understand that it applies, in many cases, to their own dogs and they continue to breed from bitches with the problem to dogs who also have the problem.” (2013). Of course there are some top class Shelties; I have long liked the Stormhead dogs, having first seen them in the mid-1950s. In recent times, I have seen sound dogs from the Myter kennel of Mrs Mylee and Miss Shannon Thomas in Buckinghamshire, their Myter Guilty Pleasure JW in particular. It is good too to see fewer timid Shelties in the ring, with exhibits once looking as though they'd rather be anywhere else. Over a thousand Shelties are bred each year; this is a situation where an overview, with remedy in mind, from outside the breed is surely justified. This could so easily be the perfect companion breed. Scotland would then be even prouder of its native sheepdogs.