530 Being Selective

BEING SELECTIVE

by David Hancock

For so many dog-owners, choosing a new puppy brings excitement and joy. Quite often this selection is done on the basis of cuteness, eye appeal or even coat colour. The endearing bundle about to join the household for fifteen years or so is in front of you; its genetic health, its ancestors are not. The pup could live four years or fourteen, it could have an unpredictable temperament leading to immense disappointment, it could be carelessly bred with its sire and dam lazily chosen; it could go blind. Yet this purchase is going to cost thousands of pounds over the coming years, in food, vet's bills, insurance, kennel costs, etc. In the show world dogs are usually bred with regard to their written pedigree. But when pedigree dogs are sold to the general public, what really is the value of five generations of names and affixes? Who truly understands breeding as opposed to the production of puppies?

For so many dog-owners, choosing a new puppy brings excitement and joy. Quite often this selection is done on the basis of cuteness, eye appeal or even coat colour. The endearing bundle about to join the household for fifteen years or so is in front of you; its genetic health, its ancestors are not. The pup could live four years or fourteen, it could have an unpredictable temperament leading to immense disappointment, it could be carelessly bred with its sire and dam lazily chosen; it could go blind. Yet this purchase is going to cost thousands of pounds over the coming years, in food, vet's bills, insurance, kennel costs, etc. In the show world dogs are usually bred with regard to their written pedigree. But when pedigree dogs are sold to the general public, what really is the value of five generations of names and affixes? Who truly understands breeding as opposed to the production of puppies?

The selection of mates will forever be the principal factor in successful livestock breeding. So often, in the working dog world, it's done on a work-rating: how good at working are the prospective parents? In the show dog world, however often this is denied, rosette-winning is the biggest single factor, with even unworthy Crufts winners being freely used as breeding stock. This is an entirely irrational act; it is based on a view that, firstly, Crufts judges are trustworthy in their judgements, secondly that the winning dog is physically and mentally sound, and thirdly, that the chosen mate will actually 'nick' with the other mate. By that I mean, produce the quality offspring the blood behind each mate should create. As master-breeder Jocelyn Lucas wrote in his Pedigree Dog Breeding (Simpkin, 1925): "A stud dog is not good just because he is good looking. He must be bred right and not be 'chance got', or his good points will not force themselves on his progeny."

Charles Castle FZS, in his Scientific Dog Management and Breeding (Kaye, 1951), wrote: "Bruce-Lowe traced the pedigree of every racehorse back to the original dam...he was able to classify these families by their characteristics, such as 'sire-producing families', 'running families', etc...these families run true to the present day, passing on family characteristics and certain families 'nick in' to each other to produce winners..." There, was a serious enlightened breeder. As vet and exhibitor RH Smythe wrote in his informative The Breeding and Rearing of Dogs (Popular Dogs, 1969): "It is true that some kennels contrive to turn out a champion each year, but they are usually those that contain a number of bitches often similarly bred, and their owners have been fortunate enough to discover a sire that 'nicks'..." This system has a run-out date as repeat close-breeding can penalise in time.

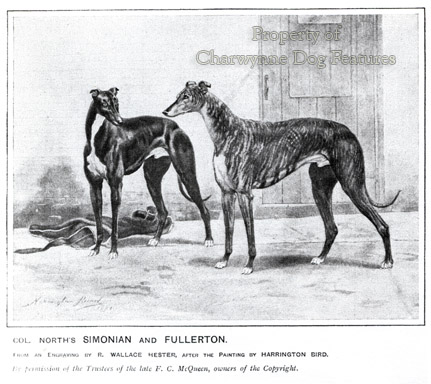

I once had a stockman who was astonishingly good at this 'nicking'; he didn't study bloodlines, he wasn't bedazzled by show ring success, he seemed to have a gift at matching sire with dam. I have heard of Irish Greyhound breeders with a similar 'eye'. But my stockman was an older man with decades of experience with livestock; he had learned not from paper but proof in the flesh. He did in fact know a great deal about bloodlines and had shown exhibits for years at agricultural shows. Breeding livestock is very much a science, but he made it into an art. There are show dog breeders with similar insight. In the Bullmastiff world, for example, distinguished and highly successful kennels like Oldwell and Bunsoro, have long excelled at sire selection and choice of dam. Some of their very best dogs have not come from high winning parents.

Some quite sound but not truly outstanding dogs sire high standard offspring, as Bunsoro Bymesen, top sire in 2005, and Azer of Oldwell, who never became a champion but sired nine, illustrate. It is the blend of phenotypical and genotypical features which produce the offspring; top quality can skip a generation. The concept that a Crufts winner mated to an indifferent bitch can somehow produce top quality pups is seriously flawed. It is based on wishful thinking not science. The lazy thinking which leads to a good quality bitch being mated to the nearest available sire in that breed is just puppy-producing. If I were buying a Boerboel I would approach a dedicated breeder like Peter Wilson, who, in his diligent quest for quality toured the Boerboel kennels in South Africa, before he came across stock with the mental and physical attributes he was seeking. That is serious enlightened intent. All too often 'dogs only good on their papers' or pedigree-impressive dogs are assumed to be valuable breeding material. Why?

In dog-breeding, the written pedigree has a role, but should never ever be the deciding factor. Without the written pedigree declaring health details, how can anyone know the genetic health of the dog? The written pedigree can misinstruct; if you believe that it accurately sets out a dog's ancestors, then you are naive. Far too many written pedigrees are accepted at face-value; no DNA checks are routinely made to verify accuracy. I know of well-known breeders offering stud-dog A at a fat fee, but actually employing kennel-dog B, a better performer. It is fraudulent but it happens. The Danish geneticist Winge proved on coat-colour grounds alone that 15% of the Danish KC pedigrees were untrue. A serious breeder is an assiduous researcher. Honest breeding records are of course immensely valuable but it takes skill to read them rewardingly.

In emergent breeds, stabilising the gene pool and establishing type is crucial. The creator of the Plummer Terrier, sporting writer/breeder Brian Plummer at first advocated a back-cross to the 'pitbull type' but later on, as his breed developed, he changed his mind. In a telephone conversation with me, towards the end of his shortened life, he stated very clearly that he no longer favoured that approach. He was wise enough to retain an open mind; kennel or breed blindness can do much harm. Strict conformists can let a breed deteriorate; unskilled non-conformists can wreck a breed. I do hope Brian's impressive breed is in safe hands. When I judged them a few years ago, I saw sufficiently sound typy stock to make a reversion even to founder-blood quite needless.

In another emergent breed, the quite admirable Sporting Lucas Terrier, a planned outcross to a Norfolk has restored the red-tan coat colour to the breed. As a breeding advisor to the breed, I am sometimes asked about other possible outcrosses, to farm or working Sealyhams, for example. Without seeing the dogs themselves, not knowing their background, whilst acknowledging the need to expand a small gene pool, this gives me difficulties. I judged a Lucas Terrier show a decade ago and was concerned at the number of 'brown Sealyhams' in the ring. Type in a breed is everything but favouring an undesired physical signature is not breeding for the breed, just using available stock. At country shows however I do see throwbacks to the real Sealyham, the type originally used in the hunting field, not over-boned, over-coated or otherwise 'overdone'. That word summarises the all-too frequent outcome of pedigree dog breeding for the show ring; selective breeding for type stops, breeding for show ring success ensues and the breed gets 'overdone'.

Far too many breeds of purebred dog are 'overdone': Beardies, Rough Collies, Shelties, Bull Terriers, Bulldogs, Mastiffs, Fox Terriers, Dachshunds and Basset Hounds are, in my view. Selective breeding for show points has gone too far. But it would take a brave soul within the breed to attempt redress. Soon there were be a generation, if there isn't one already, which doesn't know what their breed once looked like. So much for respecting a breed and its functional origin. In The Principles of Dog-Breeding (Toogood, 1930) RE Nicholas wrote: "The breeder who returns from each show with a new rather than an improved ideal seldom accomplishes anything worthwhile, for vacillation in standards (i.e. breed standards, DH) is the direct road to confusion of types and to absolute failure. The rolling stone gathers nothing but hard knocks." Every breed needs breed-architects ahead of breed optimists.

When you breed, selectively for coat, as has happened in the Beardie, the Rough Collie and the Sheltie, you can end up with all coat and no dog. When you breed, selectively, for head-shape, you lose genuine type, as in the Bull Terrier and the Bulldog, no matter how widely accepted the new look is. When you breed, selectively, for 'stance', substance and excess of breed features, as in the Fox Terrier, the Mastiff, the Dachshund and the Basset Hound, you betray the breed's heritage and don't always put the well-being of the dog ahead of slavish perpetuation. Regrettably, overseas judges and all-rounders see loss of true type quicker than breed specialists, although it is more a matter of honesty than eyesight. Over half a century ago, as a vet's kennel boy, I went with him to Molly Harbut's Airedales, to Manson Baird's Deerhounds, Miss Lipscombe's Bull Terriers and other renowned kennels; it would be good to see such 'type' once more.

A few years ago, I judged the annual show of the Victorian Bulldog Society. There, in the ring, one gruff unprepossessing young exhibitor presented me with just about the perfect Regency Bulldog, the real McCoy - before the Victorian breeders squashed the face and ruined the forequarters of this admirable breed. It was a joy to view such a dog; Clifford Derwent, who tried with his recreated Regency Bulldog to replicate the old type, would have loved him. The owner-exhibitor said his Dad had always bred 'em like that! His Dad, it appeared, had stubbornly selectively bred what he considered to be a 'proper Bulldog'; Oh! for more like him! This dog had a muzzle! It could run without wheezing, it was agile, athletic, hard-muscled and sound. I thought back to this splendid dog with fondness, when, a few weeks later I saw KC bulldogs being judged at the Bath Dog Show at Bannerdown. The Dad of my young exhibitor handling the Regency Bulldog look-a-like would not have liked what was on parade that day; he had long bred for the dog not the ticket.

It is perfectly possible to breed selectively for soundness. The soundest breed I see in the show ring, abroad admittedly, is the American Staffordshire Terrier. They are unexaggerated, supremely fit, superbly constructed, uniformly typy and impressively 'like themselves'; they look, even in a ring of thirty, as though they all came from the same dam. American Bulldogs can look very different, one from another, as different kennels favour different types. But each appears to have been selectively bred to be a canine athlete. When I judged a class a few years ago, type was varied but soundness still manifested itself. Selectivity wasn't working towards one design but still producing sound construction. A dog of this size too must be bred with temperament in the forefront of the breeder's mind.

In his enlightening book How To Breed Dogs (Orange Judd, New York, 1947) the highly experienced dog-breeder Leon Whitney wrote: "Now, as every breeder knows most dogs are bought on the basis of what cute puppies they are. The buyer hardly stops to ask, 'Will it have a calm even disposition when it is grown?' Nor does the breeder usually stress disposition. Instead he brags about the wonderful champion show dogs in the pedigree - anything to sell the pup. Why can't breeders all realize that what makes dogs lastingly popular is first, disposition?" If the general public buy puppies without any regard to their likely temperament, is it at all surprising that children get bitten, breeds can get a bad name as a result and fewer sales in that breed ensue.

Surely it is the very first question any responsible parent should ask when selecting a future family pet: 'What is the temperament of the parents and previous litters from this mating?' What possible solace is there in saying later, in sorrow, 'but it was such a cute puppy!' Even accredited breeders are not obliged to put temperament high on their list of desired qualities. Is this the best way to promote the breeding of companion animals? Is this the best way to improve the man-dog relationship? Selectivity really does matter.