523 THE SHEPHERDS' MASTIFF

THE SHEPHERDS' MASTIFFS

by David Hancock

“The shepherd’s masty, that is for the folde, must neither be so gaunt nor so swifte as the greyhound, nor so fatte nor so heavy as the masty of the house; but verie strong, and able to fighte and follow the chase, that he may beat away the wolfe or other beasts, and to follow the theefe, and so recover the prey. And therefore his body should be rather long than short and thick; in all other points he must agree with the ban-dog. His head must be great and smooth and full of veins; his ears great and hanging; his joints long; his fore legs shorter than his hinder; but verie straight and great.”

“The shepherd’s masty, that is for the folde, must neither be so gaunt nor so swifte as the greyhound, nor so fatte nor so heavy as the masty of the house; but verie strong, and able to fighte and follow the chase, that he may beat away the wolfe or other beasts, and to follow the theefe, and so recover the prey. And therefore his body should be rather long than short and thick; in all other points he must agree with the ban-dog. His head must be great and smooth and full of veins; his ears great and hanging; his joints long; his fore legs shorter than his hinder; but verie straight and great.”

From the translation by Barnaby Googe of Conrad Heresbatch’s Four Bookes of Husbandrie, published in 1586.

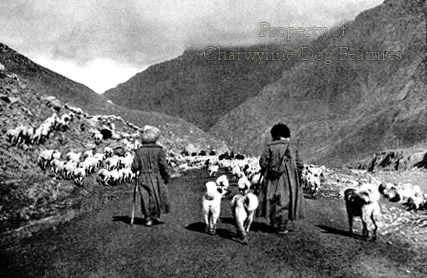

As discussed in the previous section, powerful dogs bred to protect livestock have been utilized from the upland areas of Iberia in the west, right across to Iran and on to the highlands of Eastern Europe, from mountainous Balkan regions in the south and northwards to former Soviet states. Sometimes they are called shepherd dogs, others mountain dogs and a few dubbed 'mastiffs', despite the more precise use of that word in modern times. Their coat colours can vary from solid white to dark-grey and from a rich russet to solid black, often with tan. Many that developed as breeds are no longer used as herd-protectors and their numbers in north-west Europe seriously declined when the use of draught dogs became a victim of the mechanized age. A number of shared features connect these far-flung types: a dense weatherproof jacket, a substantial build, an impressive magnanimity and a strong instinct to guard livestock placed under their supervision. As a group, they would be most accurately described as the flock guardians; in Britain in the distant past they were referred to as 'shepherd's mastiffs', but they were valued all over Europe, as the quote at the head of this section, and its source, indicates.

Ancient Value

The ancients knew the value of big resolute dogs to guard their livestock. Aristotle, writing around 2300BP in his The History of Animals, stated that: “Of the Molossian breed of dogs, such as are employed in the chase are pretty much the same as those elsewhere; but sheepdogs of this breed are superior to the others in size, and in the courage with which they face the attacks of wild animals.” Varro, wrote around 2000BP: “Dogs…are of the greatest importance to us who feed the woolly flock, for the dog is the guardian of such cattle as lack the means to defend themselves, chiefly sheep and goats. For the wolf is wont to lie in wait for them and we oppose our dogs to him as defenders.” He went on to describe these ‘guardians’ as having a stubby jaw with projecting fangs, a large head, thick shoulders and neck and of ‘a leonine appearance’; those words describe a primitive mastiff.

Wolf Threat

Our contemporary affection for the wolf would not have been shared by those living in remote villages in India or a number of European countries in the middle ages. (In fairly recent times, between 1985 and 2005, 83 livestock protection dogs were killed by wolves in the Rocky Mountain states alone - C and J Urbigkit’s review of 2010 published in the Sheep and Goat Research Journal Vol 25.) Wolves, operating in packs, have long threatened livestock and sought human prey when desperate for food. Powerful dogs of the flock guarding type were needed to protect livestock and strong-headed very fast hounds were needed to course them. Hunting wolves for sport may not appeal to 21st century sympathies, but that should not lessen our admiration for wolfhounds, their bravery and athleticism in the hunt, when wolf numbers required checking. But the shepherd’s mastiff didn’t have the protection of the pack; their’s was a lonelier task, tied to their flock and their pasture, often unnumbered. Their dedicated flock protection in remote areas deserves our admiration. In his The Illustrated Book of the Dog of 1879, Vero Shaw records: “In countries where the wolf is common and the lion not unknown, their penchant for mutton had to be guarded against, and for such use, it is probable that a more powerful and fiercer dog was employed than our modern collie. Indeed this is the case at the present day; and in Thibet the large black-and-tan Mastiffs of the country are used to guard the flocks and herds.” Robert Ekvall, writing in 1963 (Role of the Dog in Tibetan Nomadic Society, Central Asiatic Journal, Vol 3) found 21 dogs, of Tibetan Mastiff type, or 3 and a half dogs per tent, when living for several weeks in an encampment of just six tents.

The Tibetan Dogs

Time and time again you will find writers on these breeds linking them with an origin from the Tibetan "Mastiff". But I believe all such big mountain dogs or shepherd dogs share a common origin and came south with migrating people, ending up in the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Balkans and the foothills of the Himalayas. I can find no evidence of the Tibetan Mastiff existing before the Kuvasz, for example. It disappoints me therefore to see the St Bernard being bred more like a mastiff than a mountain dog. Historically, the hospice dogs were much more like the other mountain breeds and did not feature the massive head, loose lips and excessive dewlaps of the modern pedigree St Bernard. I can never see the rationale in extolling the proud history of a breed and then perpetuating that breed in a different mould. Huge dogs have a magnanimity, a munificence and a majesty all of their own and simply don't need exaggeration to promote themselves or win our admiration.

The Tibetan Mastiff has recovered from the absurd claims of Victorian and early 20th century zoologists, natural historians and even some archaeologists that the breed represented the original mastiff, whence came all mastiff-types in the West. They are bred now to resemble what they have always been big strong livestock protection dogs, thick-coated, strong-muzzled and physically extremely robust. In their The Tibetan Mastiff – Legendary Guardians of the Himalayas of 1989, Ann Rohrer and Cathy Flamholtz wrote: “The Tibetan Mastiff holds a very special place in the hearts of the nomadic sheepherders. Perhaps they, above all, can truly appreciate the breed. The nomads, with their black yak-hair tents and large flocks of sheep, goats and yaks, resemble whole towns, temporarily halted in their eternal wandering. They live life on the move, roving from one highland pasture to another.” In this informative book, the authors describe the caravan dogs, used to protect a convoy of goods for trading, including livestock. They point out that: “Appearance was of no particular importance to the caravan man. In order to effectively perform his job, however, the caravan dog had to have certain attributes. Imposing size, heavy bone, power and agility were musts. However, size could never be so exaggerated that it interfered with function. A giant cumbersome dog just couldn’t keep up with the rigors of caravan travel.” There is a strong message there for all breeders of large pastoral dogs. It is worth a look at one classic example of such a breed to assess its contemporary quality.

The Breed in Britain

It was good to read, in a critique on the Tibetan Mastiff Club Show of 2003, these admiring words: “It is some years since I have judged the breed in this country and was amazed to see what progress has been made in uniformity of type and conformity to the Standard. Gone are the square, long-legged, plush-coated, Chow-headed dogs of yesteryear…Most were well ribbed-up with length of ribcage and compact loin, giving the desired body:height ratio. There has been a big improvement in strength of hindquarters and set of hocks.” All the points made are of importance to such a breed. The Finnish judge of the breed at Crufts in 2007 made these observations: “The entry at Crufts posed me with many problems as the variation in type was extensive. The dogs ranged from tall and leggy to small and low to the ground. Several were long cast whereas some were too short in body and too high on the leg.” Such comments are worrying; this judge pointed out that similar problems had been encountered but overcome in Finland. When I saw the breed at the Helsinki World Dog Show, I was impressed with the quality there. In 2009, judges of the breed here reported some alarming faults: poor hind movement, clicking hock joints, straight stifles and too long a hock (in other words exaggerated angulation), faulty front movement, weak hocks and too close a movement in the hind legs. A year later, a judge expressed disappointment in the quality of movement, lack of layback in shoulder, weak and close rear movement with the exhibits showing good breed type having less quality than those without. But in 2012, it was reassuring to read a critique stating: “I enjoyed seeing the progress that has been made since I last judged the breed in 2009. Fronts have improved greatly and rear angulation is better. Rear movement is improving, though still some way to lose cow hocks completely.” This is a magnificent ancient breed, developed in the hardest of schools and meriting the very best custodianship.

Medieval Laws

Any breed developed the drive off fierce and savage predators needs the strength, stamina and intense dedication to do so. Such powerful dogs have long been valued. In medieval times, there were laws under which some court fines were assessed in terms of wolves' tongues. At one time, the yearly tax in Wales was established at 300 wolves' heads. France was one country particularly populated by wolves; as early as 1467, Louis XI created a special wolf-hunting office, whose top member was appointed from the highest families in the land. In the French province of Gevaudan in the 1760s one wolf is alleged to have killed more than fifty people, the majority women and children. At the end of the French revolution in 1797, 40 people were killed by wolves, tens of thousands of sheep, goats and horses slaughtered by them, and, in some remote districts not a single watchdog left alive. The dense forests led to the French mainly hunting them with packs of scenthounds rather than coursing them with faster hounds. But in the remote pastures, the shepherd relied on his ‘mastiff’.

Use in the Hunt

In Britain once the wolf had been exterminated, the need for flock guardians or shepherd's mastiffs disappeared, but all over Europe, strapping herding dogs continued to be favoured, if only to protect flocks and herds being driven to distant pastures and markets from human threats and village curs. The drovers of Britain used the Smithfield Sheepdog (a leggy, shaggy-haired shepherd dog, named after the London market of that name), what became the Old English Sheepdog and in Wales the Welsh Hillman. Some of the fiercer ones became involved in the European stag, wolf and boar hunts, not as hounds, but as ‘matins’, expendable 'catch-dogs', sacrificed at the kill to save the more valuable, better-bred hounds. Hondius, Oudry, Snyders and de Vos all captured both the ferocity and the canine sacrifice in such dangerous employment.

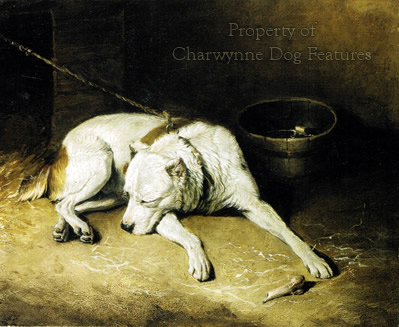

Perhaps inspired by living in the Windrush Valley in Oxfordshire, classic grazing fields for drovers en route to markets to the south-east, I once tried my two young Bullmastiffs as flock guardians, with the consent of a local farmer. Handicapped by not having been weaned alongside sheep, but naturally protective and responsive to new training, the two powerful dogs soon understood that they were to guard the fields and me, the temporary shepherd. They responded immediately to any dogs passing by (a public footpath crossed the pasture) and soon learned to ignore the sheep (and the prospect of mutton!) But the most informative reaction was from the sheep; they very quickly relaxed with two big dogs lying down in their field and, more importantly, followed the dogs when I led them around the perimeter of their pasture. If it’s not wishful thinking, the sheep seemed to know they were expected to follow the dogs – and did so. The relaxed laid-back attitude of the hefty dogs no doubt removed any hint of threat to the sheep from them. But I could see at once the immense value to a shepherd of a powerful dog, left alone to guard his flock.

The ease of modern living has led to our devaluing the contribution made throughout human history by the flock protectors, but our ancestors prized them and developed them as highly impressive, extraordinarily robust, canine specimens. We must be careful with the surviving breeds not to substitute show-ring criteria for functional need. Huge cow-hocked, straight-stifled, over-coated, under-muscled shepherd's mastiffs would not have lasted long in the demanding pastures of past centuries. Our respect both for our rural heritage and those breeds surviving man's changing requirements needs to be demonstrated by a seeking of soundness before ‘stance’ and fitness ahead of flashiness. These quite remarkable faithful, selfless, admirable dogs, often killed by marauding packs of predatory wolves, deserve no less. With around 330 sheep currently being killed annually by bears, reintroduced from the Czech Republic into the Pyrenees, perhaps the reintroduction too of the shepherd’s mastiff, more determined than the mountain dogs, would be timely.

“Many hundreds of years ago, when our island was principally primeval forest, with few clearings, it must necessarily have been infested with wolves, bears, and the lesser British carnivorae, and to protect the flocks and herds it must have been requisite to have a large and powerful dog, able to cope with such formidable and destructive foes, able to undergo any amount of fatigue, and with a jacket to withstand all vicissitudes of weather, for his avocation was an everyday one; day and night, and in all weathers, was he watching and battling with heat and storm and marauding foes. What other dog but the old English sheepdog possesses attributes necessary for the multifarious duties urged upon such a business?”

From Rawdon Lee’s Modern Dogs of Great Britain and Ireland (Non-Sporting Division) Horace Cox, 1894, quoting the leading expert on the breed at that time: Dr Edwardes-Ker of Woodbridge, Suffolk.