521 THE FRAUDULENCE OF SIZE

THE FRAUDULENCE OF BREEDING FOR SIZE

by David Hancock

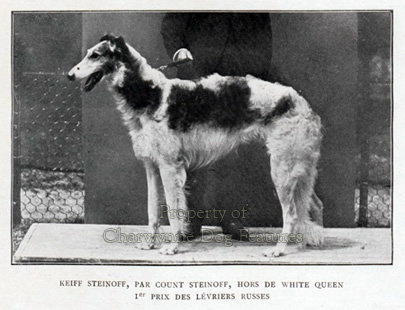

Breeding already large breeds as even bigger ones, without heeding their past, their soundness or their ease of living in the modern world is also the height of human selfishness. The early imports of tall dogs like Borzois, Deerhounds, Irish Wolfhounds and Great Danes were sadly often desired because of their stature. The Perchino kennel of hunting Borzois in Tsarist Russia bred dogs to mature to 27-8 inches at the withers; foreign fanciers would select the biggest for purchase and then breed then together to obtain even greater height. The first Deerhounds to come into the show ring contained many that were considered too tall to make good hunting dogs by their Highlands' owners. Bismarck's German Boarhounds were around 26 inches at the shoulder - as are most staghounds in France and Britain. Lord Altamont's famous Irish Wolfdogs were never as huge as today's Irish Wolfhounds. The giant bear-dogs of Russia, the Mendelans, were around 30 inches at the withers, but, sadly, they were used to seize bears for the fur hunters and needed great size. The mastiff group were hunting mastiffs needing athleticism, agility, great stamina and seizing power ahead of any shoulder-height need. They certainly did not need immense bulk.

Breeding already large breeds as even bigger ones, without heeding their past, their soundness or their ease of living in the modern world is also the height of human selfishness. The early imports of tall dogs like Borzois, Deerhounds, Irish Wolfhounds and Great Danes were sadly often desired because of their stature. The Perchino kennel of hunting Borzois in Tsarist Russia bred dogs to mature to 27-8 inches at the withers; foreign fanciers would select the biggest for purchase and then breed then together to obtain even greater height. The first Deerhounds to come into the show ring contained many that were considered too tall to make good hunting dogs by their Highlands' owners. Bismarck's German Boarhounds were around 26 inches at the shoulder - as are most staghounds in France and Britain. Lord Altamont's famous Irish Wolfdogs were never as huge as today's Irish Wolfhounds. The giant bear-dogs of Russia, the Mendelans, were around 30 inches at the withers, but, sadly, they were used to seize bears for the fur hunters and needed great size. The mastiff group were hunting mastiffs needing athleticism, agility, great stamina and seizing power ahead of any shoulder-height need. They certainly did not need immense bulk.

Bigger doesn't always mean better, especially in the dog- breeding world. In the past few months, I have attended dog shows in which dogs have been proudly presented by exhibitors when they were clearly just too big for their own well-being; this is not wise. Breeds like the Boerboel, the Bullmastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Neapolitan Mastiff and the Mastiff were never intended to be admired and valued because of their size but for what they could do. The Boerboel is and was the South African 'farmer's bulldog', needed to drive wayward bulls, protect livestock from predators and lead an active life on a vast farmstead. It was not designed to pull carts or engage in weight-pulling contests of little consequence. It was always a working dog. Similarly, the Bullmastiff was bred to be active and powerful not inactive and immense. A Bullmastiff weighing more than 130lbs breaches its own breed standard and should not even be seen by a judge. Why breed away from function when it always creates problems and leads to a loss of true breed type?

A couple of years ago, I watched the Mastiff of England being exhibited by foreigners at a World Dog Show. I could have wept. The dogs were simply dreadful, sluggish, shambling, overweight specimens of a superb breed 'gone wrong'. Their movement was awful; their construction disastrous; their eyes sunken and sad; their flews exaggerated beyond comfort and their ultra- heavy bone a needless handicap. I was appalled. Any group of breed fanciers can lose their way, but when a dog of this size is ill-bred, indirect cruelty is involved. These dogs were heavier than any past function could ever justify; they appeared to be valued because of their extreme bulk.

Writing in 'The Book of the Dog' of 1948, edited by Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald and published by Nicholson and Watson, Arthur Croxton Smith gave this view: "Breeders seem to have concentrated more and more upon getting immense size, and great bulk usually brings the evil of unsoundness in its train. I have seen plenty of perfectly sound mastiffs, such as could move well and were really active, but latterly the proportion of unsound ones has been alarmingly heavy, for it is extremely difficult for breeders to get soundness in alliance with bulk." No breed can lead a healthy life if its whole design is at the mercy of human whim. Any breed no longer bred for a function, even if that function has lapsed, has a doubtful future.

If youthen look at the health of the breed as summarised in an authoritative book such as 'Medical and Genetic Aspects of Purebred Dogs' by Clark and Stainer (1994), youcan see some of the problems in the breed. It states: "Many bitches experience uterine inertia after whelping one or two puppies, probably resulting from the breed's characteristic lethargy...Obesity is the curse of the Mastiff breed...many owners continue to overfeed their dogs in the mistaken belief that the heavy feeding increases the dog's size."

Lethargy and obesity from overfeeding, are these not the consequences of breeding for great size without accompanying soundness or quality? I groan when I read a judge's critique praising 'great bone'; are we breeding cart horses or powerfully-built physically-sound dogs? The seeking of massive bone in any breed of dog is not a rational act. Strong flat bone is admired by every racehorse owner, because it is the strongest, and who in all honesty wants a dog with thick ankles? Of what use and value are they to the dog? Did our distant ancestors, who actually used these dogs in the field, ever value a dog purely for its bulk? The Mastiff of England is an imposing breed, developed because of its athleticism not its size; now a veterinary author refers to "the breed's characteristic lethargy". It is dishonest to boast of a breed's historic feats and then breed an animal that simply could not accomplish such a task.

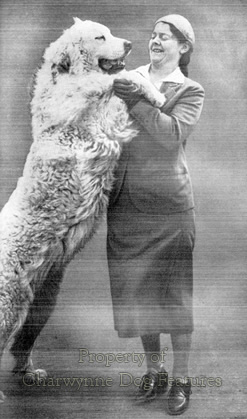

In my working life, my shire horses displayed better movement than many Mastiffs in today's show rings. And they were designed with hauling strength mainly in mind. Great size without soundness and weight for weight's sake are pointless achievements in a dog. The late Natalka Czartoryska had an Anatolian Shepherd Dog, over 30 inches at the shoulder, that moved simply effortlessly. When working in Germany, I have seen Great Danes with movement of such power that it took your breath away. I have seen Caucasian Owtcharkas, as big as any Mastiff, with such strength on the move that they simply devoured the ground. Huge dogs don't have to be ponderous.

No breed of dog benefits from being too big, that is a human desire for dogs to suit their concept rather than the dog's best interests. Dogs are punished by over-heavy bone. "The search for large bone is going to bring with it an obvious increase in growth rate which in turn renders the dog more liable to such problems as OCD, UAP or FCP...." Those words by Malcom Willis in his authoritative 'Practical Genetics for Dog Breeders' (Witherby, 1992) don't seem to impress dog-breeders perhaps as much as they should. Some breeds are actually prized for the weight of their bone, with many judges seeking heavy bone in exhibits, if their critiques are anything to go by. A century ago, Foxhound breeders lost their way and sought hounds with heavy dense massive bone, claiming that this feature provided stamina. They themselves however, when riding to hounds, rode hunters not cart-horses - and still managed to keep up! Their folly was subsequently exposed by a hound-expert from America, the legendary 'Ikey' Bell, whose influence ended the so-called 'shorthorn' period in Foxhound packs.

Strength, power and endurance do not reside in heavy bone, as any dog-sledder will tell you. To breed dogs with bone heavier than nature intended is asking for trouble, as the statistics on hip and elbow dysplasia, cervical vertebral malformation and osteochondrosis sadly demonstrate. The Mastiff of today seems to be bred for beef not any previous canine function; a Mastiff exhibitor at Crufts once boasted to me of the heaviness of his dog's bone but heavy bone is not required in the Mastiff's standard. A Mastiff breeder advertised his stock in the dog-press a few years ago by claiming 'I am pleased to say that we have now bred the largest and heaviest dog in Britain', boasting of a 35" dog weighing over 20 stones. The two great Mastiff breeders at the end of the 19th century, Wynn and Sidney Turner each favoured dogs around 29" high and around 10 stones in weight. Both prized soundness in their Mastiffs.

Hip and elbow dysplasia are painful and potentially crippling malformations of the joints. Many elderly humans know only too well the appalling discomfort of arthritis. To breed dogs of such body weight and bone density that they suffer cruelly from such afflictions is hardly admirable. But if show judges are actually rewarding massive bone, then cruelty to dogs is seriously being encouraged. In his valuable book 'The Anatomy of Dog Breeding' (Popular Dogs 1962), exhibitor and vet RH Smythe writes: "When a judge picks a dog out of a breed class for honours because he considers that it has better bone than its rivals, he is probably under the impression that the bones of its limbs (and he usually considers the fore limbs from elbow to knee) are thicker and stronger than those of other exhibits….it is only the mineral content of the outer casing which gives strength to bone.. .we must not delude ourselves into imagining that the increase of 'substance' implies extra thickness of bone."

The accomplished hound breeder Sir John Buchanan-Jardine once gave the view that 'Great weight of bone is unnecessary and rather a hindrance than the reverse.’ It is of course the muscles which control the bones not the other way round; muscular development is far far more important than the thickness of the bone. It is a lazy response to state that 'what applies to Foxhounds doesn't apply to my breed'. The lessons learnt by any breeder in any field are worth heeding. To prize a dog mainly because of its weight is astonishingly shallow. To boast of an unsound dog's shoulder height and poundage is, to me, a sure sign of a limited personality. To be proud of a sound big dog is surely, in the larger breeds, every good breeder's aim; leave size-boasting to the socially inadequate.

Twenty years ago, one vet, Simon Wolfensohn, covered this subject in New Scientist magazine, writing: "There is no simple explanation for the shorter life-span of the giant breeds...apart from those that are destroyed because of bone problems early in life (usually due to faulty development of the growth plates of the bones or defects in bone mineralization) or because of severe arthritis...it may be that the hormonal mechanisations or other factors responsible for the giant size and heavy bone development of these breeds are intimately related to the aging process."

He took the view that St Bernards and Bloodhounds have a strong inherited tendency to acromegaly, a condition caused by excess production of growth hormone in the adult, which leads to heavier than normal bone structure, especially in the feet. Article 5 of the European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals, at last receiving some official attention here, takes account 'of the anatomical characteristics which are likely to put at risk the health and welfare of the animals.' We need to remind ourselves of the times we live in. Do we really want unseemly public outcries over dogs bred with harmful features, such as 'great bone' and massive size, in breeds that never originally featured it and are handicapped by it? Breeders of an established working breed like the Bullmastiff and an emergent working breed like the Boerboel need to look at what happened to the Mastiff and think again about size; it matters!

A parallel situation is caused by the seeking of great height in some breeds, as the Great Dane, the Irish Wolfhound and the Scottish Deerhound demonstrate. The breed of dog known in Britain as the Great Dane is, with the Irish Wolfhound, our tallest breed. The Kennel Club, in its Breed Standard or word picture, for this breed sets a minimum height for a dog over 18 months at 30 inches and a minimum weight for such a dog at 120lbs. Our Deerhound is also expected to reach this height but, understandably for a sighthound breed, weigh 20lbs less. The American KC prefers a mature Great Dane to be 32 inches at the withers. The Irish Wolfhound has to be a minimum height of 31 inches. But the Great Danes I see both at Championship Shows here and at World Dog Shows are usually over 31 inches at the withers. Is the pursuit of such size a benefit to the breed or even historically correct?

The boarhounds bayed the boar but did not close with it - that was the task of the catch-dogs or seizers, many of whom died in the hunt, the boar being a fearsome adversary. Quite a number of French packs of hounds still hunt the boar, but their hounds are all around 24-26 inches at the shoulder; this has been decided by function not their national kennel club. To hunt the boar a hound has to be agile - or it dies! Far too many of the show Great Danes are not exactly nimble on their feet, being bred for size ahead of any 'fitness for function' criterion. For a French boarhound to be preferred at six inches lower at the withers than a German one comes directly from field experience, not from any desire to seek great height purely for aesthetic reasons. Apart from seeking a dog too large for the task, what is being overlooked by show breeders is that the German boarhound (of the hunt) was never that huge. The added stature came from their use as 'Parade Dogs' or mascots by German regiments, rather as the Irish Wolfhound leads parades of the Irish Guards. These Parade Dogs had to impress in size and so were crossed with the Suliot Hounds, used by the Ottomans as outpost sentries in war. These Suliot Hounds came from the Suli Mountains of Epirus in Greece, where the Molossii were based, making them the contemporary form of the ancient Molossian Dog. This added height from the Parade Dogs found favour when the German boarhound found its way to the early show rings, those of England especially.

For a Mastiff breeder to boast of the immense weights of his dogs as a lure to would-be purchasers is simply a betrayal of this now-forlorn breed. Breeding for great size often tells you more about the breeder than the dogs! To watch an indulgent exhibitor parading, with misplaced pride, a thoroughly unsound, needlessly giant dog around a show ring, studied by apparently serious judges, is beyond parody; if anything it is indirect cruelty, and both the exhibitor and the judge should be heartily ashamed of themselves for such blatant if indirect cruelty. Great size, in either height or sheer bulk, is misguided and fraudulent; it must be stopped. These substantial dogs deserve better - far better!