520 Fighting for Dogs

FIGHTING FOR DOGS

by David Hancock

Organised dog-fighting has a feature which is unique amongst criminal activities: a successful prosecution brings the greatest punishment to the victim. The convicted humans receive jail sentences or a substantial fine; the dogs forced to take part are sentenced to death, those which survive death in the ring, that is. There is rightly little sympathy for the human culprits; sadly there is no compassion for the dogs. I appreciate the manifold problems of rehoming dogs made to fight each other; I just wish some form of rehabilitation for them could be attempted. It is rare, I believe, for a dog used in organised fights to be aggressive towards humans, despite the justification which might exist for that.

Organised dog-fighting has a feature which is unique amongst criminal activities: a successful prosecution brings the greatest punishment to the victim. The convicted humans receive jail sentences or a substantial fine; the dogs forced to take part are sentenced to death, those which survive death in the ring, that is. There is rightly little sympathy for the human culprits; sadly there is no compassion for the dogs. I appreciate the manifold problems of rehoming dogs made to fight each other; I just wish some form of rehabilitation for them could be attempted. It is rare, I believe, for a dog used in organised fights to be aggressive towards humans, despite the justification which might exist for that.

It is difficult to fathom the rationale behind dog v dog contests, which are staged from Mexico to Milan and from the Himalayas to the Philippines. Gambling of course has always played a major part in such odious activities and surviving winners can command relatively huge fees in breeding programmes. But what kind of man participates? Do they consider themselves 'hard' by taking part or consider it a way of demonstrating their toughness? I have had the privilege of working and playing sport with some of the toughest men you could find: I played rugger for England as a schoolboy; I went on two arctic expeditions before I was 21; I was a paratrooper for three years; I served in Gurkha formations in both Malaya and Borneo. I have learned from personal experience that there is a world of difference between being tough and acting tough; those who try to appear tough by engaging in cruel activities unwittingly reveal their actual lack of toughness immediately.

21; I was a paratrooper for three years; I served in Gurkha formations in both Malaya and Borneo. I have learned from personal experience that there is a world of difference between being tough and acting tough; those who try to appear tough by engaging in cruel activities unwittingly reveal their actual lack of toughness immediately.

Yet, dog-fighting is a popular village sport in places like Afghanistan and Nepal. The Gurkhas were honest about it, the cash rewards from gambling on the dogs were the main attraction. I have heard of a well-educated very civilised wealthy American lawyer who kept fighting dogs because he admired courage in his dogs. I was once asked by some travellers whether my Bullmastiffs were 'game', a word often used as shorthand for a willingness to fight. Apart from the fact that the mastiff breeds have an instinct to seize and hold rather than savage and would be completely unsuitable for fighting, I have always been able to respond with 'Why on earth would I want them to be?' (This in the knowledge that two different veterinary surgeries have praised my dogs for their wonderful temperament, when being treated). Making your companion dogs, quite needlessly, display their courage, pluck, gameness, ferocity, aggression, whatever you choose to call it, seems to me to be a very transparent cover for human cowardice. Bravery by proxy is not bravery at all.

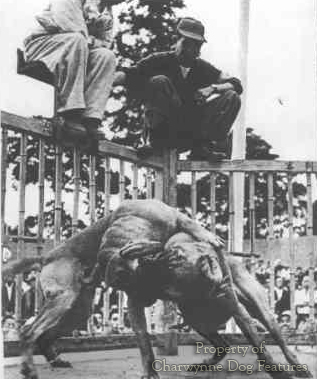

But where are the studies into dog-fighting, why it's conducted, how it's justified and what is its purpose? Is there a distinct sort of personality who is attracted to such a barbaric activity? It has appealed to all types from Lord Camelford to Bill Sykes, but are they the same type under the skin? Lord Camelford owned a dog called Belcher which survived 104 fights; it is not recorded how many dogs he was made to kill. When two champion dogs Boney and Gas fought each other at the Westminster pit on January the 18th 1825, the pit was illuminated by chandeliers and over 300 spectators attended. They would have been a mixture of street hooligans and 'young bloods', as street hooligans of nobler birth were described in those times. Did such men feel  tough by attending such an activity? Did they think they would be regarded as 'hard' if they patronised such a place for such an activity?

tough by attending such an activity? Did they think they would be regarded as 'hard' if they patronised such a place for such an activity?

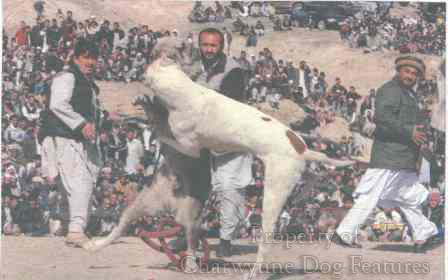

In Afghanistan, dog-fighting although banned by the Taliban, is once again the equivalent there of soccer here, it is so popular. Kabul is the hub of this national passion,, with each fight attended by thousands. The dogs are strongly-made dogs of the Powendah type, their ears are cropped off, their tails all but removed, and the value of a successful dog quite remarkable for such an impoverished country. A top fighting dog can realise 500,000 Afghanis (in the region of £7,0000). At a top fight two million Afghanis can change hands, with gambling also attracting relatively huge wagers. Most of the dogs' owners are former military commanders who made fortunes during the years of civil disorder. Weekly fights take place at Badam Bagh, a rundown northwestern suburb of the capital. Dog fighting there is associated with power, it seems to make the participants feel like men with status, influence and deserving envy.

But even here where there is a long history of organised dog fighting, the dogs are given a high fat diet to ensure their outer layers are substantial enough to withstand bites, and despite the blood, these fights are not allowed to produce fatalities, unlike those of Mexico and North America. There, the dog's bite strength is bred for and fatalities are common. It is this awe-filling bite-strength, outdone only by the hyena and the wild dogs of Southern Africa, which makes the American Pit Bull Terrier such a danger when it does bite a human being. Bigger dogs, like the mastiff types, can grip for longer but will never inflict such damage. Their jaws were designed for gripping and holding, not tearing or slashing.

The development of a mastiff breed like the Tosa for dog-fighting in Japan, was in pursuit of a 'mouth-wrestler' rather than a 'flesh-tearer'. It is a wholly different form of dog v dog combat and has sadly given the breed of Tosa a bad reputation here. Again this is punishing the dog for man's misdeeds. The Tosa is kept as a family dog all over America and Europe, without concerns about its temperament. At foreign dog shows they are exhibited uneventfully and I know of no judge who has had problems examining their bite. This is not true of several other foreign breeds which are not banned here. The Tosas of Koochi District in Japan are made to fight by local criminals seeking financial gain; the dogs do not choose to fight and need considerable training before they do so.

A century ago the calmer quieter more skilful dog was preferred; now it seems the 'fight-crazy screamers' are desired. Both in America and Ireland, a century ago, fighting dogs were preferred to be quiet whilst fighting. Silence was interpreted as stoicism, held to indicate courage, and was prized. The Staffordshire Bull Terrier was a silent fighter and much respected as such. But the spectators at such dog-fights were reported in subsequent accounts to be highly vocal, bloodthirsty and seeking savagery in the ring. There is a hint of humans admiring the dogs' qualities but not being able to match them. Again, bravery by proxy. It might even be a desire to witness stoic bravery out of sheer envy; it is certainly not very admirable supporting an activity in which dogs actually fight for their lives. That's pure sadism.

If you take just one large American city like Houston, Texas, where organised dog-fighting is a serious problem, several hundred thousand Pit Bulls are reportedly owned. Whenever a fight-scene there is successfully raided, all the dogs found are humanely destroyed. But is that humane? The wretched dogs are only doing what their owners have forced them to do. The video evidence produced in such prosecutions are just too sickening to view for any length of time. What research has been conducted over any likely success rate in retraining such cruelly-misused victims of man's baseness? Animal rescue agencies are overwhelmed in many places but it does seem grossly unfair for misused dogs to have to pay the supreme sacrifice. In Houston, this policy could mean perhaps that  several thousand dog-fight victims die each year. A further sadness is that so many of these dogs are physically well above average for soundness and fitness. Who fights for them?

several thousand dog-fight victims die each year. A further sadness is that so many of these dogs are physically well above average for soundness and fitness. Who fights for them?

In an honest desire to support those involved in combating dog-fighting, I contacted both the RSPCA and the police service with the greatest experience of dog-fighting, the Met, some six months ago. I explained that I was writing this piece, attempting to understand the motivation of those involved. I explained my aim of providing readers to a greater degree than the usual, often fact-free over-emotional, newspaper coverage. I asked just five simple questions. 1. What is the profile of a typical criminal involved in such misdeeds? 2. What is the liklehood of involvement too in the drugs trade or in gambling syndicates? 3. Are there links between between child abuse and dog abuse? 4. What are the main reasons why such barbaric activity is conducted by the participants? Kudos, gambling, stud fees, sale of pups, enjoyment of violence itself, family history of it, intense desire to be a 'winner' at something? And 5. How can the public help you in combating this activity?

I approached the press office of each organisation, explained that I was a freelance writer, obtained the appropriate FAX number, and forwarded my five questions. To date I have had no response, despite a polite reminder three months after my initial request. Now I have five further questions! 1. What really is the point of a press office of it doesn't serve the press? 2. If you have absolutely no interest whatsoever in providing information to better inform the public, how can you win their support in the campaign to stop dog-abuse in this way? 3. Are you, the RSPCA and the Met, really serious about combating dog-fighting or do you just react to the actual staging of the fights themselves? 4. Are you truly just not interested in enlisting the support of the dog-press and, through them, the eyes and ears of the dog-owning public? 5. Does your total disinterest in helping one honestly-intentioned writer exemplify your contempt for the dog-owning public.

Dog-care isn't just about looking after your own dog, there is a wider moral mandate on us all: the ceaseless striving to enhance the well-being of the domestic dog, in any way we can. But who are the bodies with formal responsibilities for dog care, dog control, dog welfare. On dog control, authority seems to rest with local authorities, the police service, our leading animal charity and two particular government departments, DEFRA and the Home Office. The police service seems to rely on the advice provided by its dog handlers, which is rather like expecting a tank driver to set policy and strategy on armoured warfare. And we all know the policies of the Essex force from their suspension of their own dogs on choke chains over fences. In my past correspondence with the Met's dog-handling section, I have been singularly unimpressed by their knowledge of dogs. That is of course, when they bother to respond at all.

The persecution of dogs by the RSPCA is well documented. One enraged Irish Staffie owner recently described this organisation to me as: 'a politically-motivated, agenda-led, anti-bullbreed, morally-vain, self-regarding, uncharitable organisation undeserving of public donations and respect.' I can see why he feels like this. The RSPCA was once admired by us all; no longer. They could do so much more to protect powerful dogs from cruel ownership. Government departments like The Home Office and DEFRA have long lost public confidence; nowadays they richly deserve public scorn. But they have clear and important responsibilities for dogs and dog control which they simply do not carry out. No knowledgeable informed body considers that breed-specific legislation is other than harmful to dogs. I wish the Kennel Club every success in striving to  change their minds, just as the KC has altered its own stance.

change their minds, just as the KC has altered its own stance.

There is a vast untapped lobby for dogs out there; you only have to read the dog papers and magazines to come across scores of quite admirable people trying to improve the lot of the domestic dog. Is it good enough for government departments to ignore attempts to work with them on dog control; lobby your MP over such arrogance. Is it helpful when the RSPCA and the Met ignore public requests for information which could contribute to their work in preventing dog abuse? A vast untapped lobby ever ready and willing to support bodies engaged in preventing dog abuse is being largely ignored. And when these bodies show little but contempt for the general public and haven't the wit to enlist their help, it is easy to despair, but that does little for dogs.

When we read of a dog-fighting gang being caught and punished, we applaud. When we learn that all the canine victims have received the ultimate sentence - death, we are, as a nation, strangely unmoved. That is not my idea of justice. In Denmark, what they term 'muscle-dogs' are now being singled out for special attention; so they should be and it should be special protection, often from their owners. We cannot claim to be compassionate or civilised when we tolerate injustice.

|

|

|

|

|