506 CAN THE SPORTING TERRIER SURVIVE

CAN THE SPORTING TERRIER SURVIVE?

by David Hancock

Terrier breeds which emerged in Britain in the 19th century, whatever their origin, are, with a few exceptions - like the Border Terrier, markedly different in some respects nowadays from the stock shown at early dog shows. Some of these differences are displayed in even shorter legs, in breeds which already featured short legs, even longer muzzles (and narrower in Fox Terriers) and greater cloddiness, as in the show Sealyham. But even more noticeable, are the far heavier coats, in today's Scottish Terrier for example, and, sadly in so many terrier breeds, upright shoulders and no falling away at the croup.

Terrier breeds which emerged in Britain in the 19th century, whatever their origin, are, with a few exceptions - like the Border Terrier, markedly different in some respects nowadays from the stock shown at early dog shows. Some of these differences are displayed in even shorter legs, in breeds which already featured short legs, even longer muzzles (and narrower in Fox Terriers) and greater cloddiness, as in the show Sealyham. But even more noticeable, are the far heavier coats, in today's Scottish Terrier for example, and, sadly in so many terrier breeds, upright shoulders and no falling away at the croup.

These two latter features are responsible for the greatly-abbreviated front and rear stride in these breeds, resulting in movement falsely described by some as a "terrier action". This lack of extension, fore and aft, can never be acceptable in a sporting terrier, especially an earth-dog. Kennel Club recognition has undoubtedly brought uniformity to these breeds and perhaps greater beauty. But beauty, in a terrier, at the expense of function, is an empty gain. Function dictates form in quadrupeds and form contributes both to health and quality of life. I shudder when I hear a TV commentator at Crufts excitedly describing sporting terrier breeds on the move as "simply flowing over the ground". Millipedes flow over the ground; dogs, whatever their size, should stride.

Regrettably, exaggerations in dogs with a closed gene pool always end up exaggerating themselves. Outcrossing to restore true type may be regarded as sacrilege by conformists. But why, once attracted to a breed, not honour its true blueprint? Why betray its original type and true form? Sadly, most show breeders are extraordinarily conformist, even when true breed type in their favoured breed is threatened. Pedigree dog breeders and dog show judges often draw an undeserved awe from the general public; some are undeniably gifted, most are very obviously not. An experienced breeder, even to the KC, all too often means someone who has bred a lot of litters, whatever their quality. Judges, similarly, can progress if they have bred prolifically from their stock.

This insanity not only leads to false reputations being gained but far too many puppies being bred. No livestock judge at an agricultural show is ever chosen on the basis of how many calves or lambs he or she has bred. Pony and hound-show judges are chosen for their knowledge not their production line. The same criterion, if applied in the world of pure-bred dogs, would represent a giant step forward. Far too many dog breeds have been at the mercy of wallet-conscious, power-seeking puppy-producers posing as experts in their field. No terrier expert would produce a dog with needless working handicaps. Terriers designed originally to work should never feature over-heavy coats, a cloddy build with little flexibility, stiff-limbed movement, ant-eater heads or limited extension both fore and aft.

The early Sealyhams were prized for the coconut matting texture of their coats; the current breed standard demands a coat that is long, hard and wiry. The dogs I see in the ring have long, soft and wavy coats. Captain Jocelyn Lucas, who worked the breed, states, in his Pedigree Dog Breeding of 1925, "A hard coat is not only a show point, but also a working one, as soft-coated dogs generally hate brambles." Today's Breed Standard of the Wire-haired Fox Terrier asks for a coat that is dense with a very wiry texture. Just before the Second World War, Rowland Johns wrote, on the wire-haired variety, in his Our Friend the Fox Terrier, that: "The harder and more wiry the texture of the coat is the better. On no account should the dog look or feel woolly...". In the show ring I see soft woolly coats on many winning dogs.

In his monumental Dogs of all Nations, published in 1904, H A graaf van Bylandt describes what we would today call a Schnauzer as a wire-haired German Terrier. The texture of coat is described as "straff" or stiff. When you look at Schnauzers of all sizes in contemporary show rings all over Europe they do not appear to feature coats with a stiff texture.

Today's breed standard for the Scottish Terrier describes the coat as close-lying with a harsh outer coat. In his book on the breed, published seventy years ago, W L McCandlish set out the standard of that time. The coat was described as rather short (about 2"), intensely hard and wiry in texture; wave in the coat was described as a special fault. The Scottish Terriers that I see winning at shows have an abundance of coat - well over four inches, with waviness, standing off from the body; so much for breed standards and a respect for a breed's heritage! The great Fox Terrier expert Rosslyn Bruce, in his book on the breed of 1950, writes: "The coat, or the outside covering or jacket, is that part of the Terrier which is perhaps the most difficult for the novice to grasp..." He might have included judges in that sentence.

Rosslyn Bruce warned against a too long-headed dog with a too short back; I see many winning dogs today featuring these two components. He was very specific on the subject of shoulders, stressing their need to be long and sloping, well laid back. He pointed out that: "Where the shoulders are well laid back the dog is at an advantage for work underground." With most sporting terriers in today's show ring, I find upright shoulders and, increasingly, short upper arms. Unless knowledgeable judges penalise this bad fault it will become a breed feature and be bred in for all time. Should we not keep faith with those who developed these splendid breeds for us?

In his book on the Fox Terrier, Rosslyn Bruce makes one statement which gladdens my heart: "...I say to the budding enthusiast: The first point to aim at in a terrier is "Character", the second "Character", and yet again the third essential is "Character"." Here is a man steeped in the exhibition world, member of the Kennel Club Committee and founder of the Smooth Fox Terrier Association, having the wit and the perception to see what makes a terrier, in any age. It is tenacity, fortitude, fearlessness, dash and perky assertiveness which makes a terrier what it is, rather than perfection of form. But these qualities alone do not make a successful sporting terrier; such a dog needs the anatomy which allows it to perform its allotted task: the control of vermin above and below ground.

Breeders of show terriers, together with those who judge them, have a duty to respect the remarkable heritage behind their dogs. They may not want their terriers to go to ground but their dogs are not terriers unless they have the mental and physical qualities for such a task. The pioneer breeders handed these precious breeds down to us to safeguard in our lifetime. It will be sad indeed if future generations inherit terriers with soft wavy coats, a short-stepping gait and a complete absence of adventurous spirit. Such dogs belong in the Toy Group; they are neither sporting dogs nor terriers.

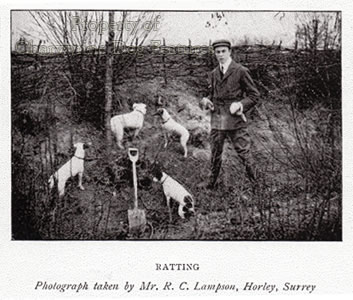

The early terriers had the weatherproof coat, the extension in their limbs which allowed them to function and the never-say-die attitude which made them invaluable to man in farms and factories alike. I have vivid memories, as a boy, of the wire netting going round the ricks and the terriers being loosed, to kill over 200 rats per rick despite the odd bite. No machine could ever do that - or chemical. Gassing or poisoning is a dreadful way to control rats; terriers are fast and efficient. Anyone with a bored teenaged son should give him a copy of Brian Plummer's classic "Tales of a Rat-Hunting Man", it's lively, amusing and uplifting - just like terriers themselves!

In America, Airedales have their own specific hunting trials; can we really not do so here? I live near dog owners who get upset when their terriers are combative and feisty but are unconcerned when their dogs bark all day, every day. Terrier spirit is part of every sporting terrier's make-up, it comes with the dog and is not difficult to redirect.

If sporting breeds are to survive there has to be a planned renaissance, not an abrogation of responsibility for breeds we specifically bred and developed over several centuries to assist us in the sporting field. It would be a major step forward if breed clubs took up this challenge, although I suspect that challenge certificates have more appeal for them. Just as the UKC in the United States fathers a wide range of field activity for dogs, so too could our own KC, extending their field trial and agility interest. Sporting organisations too could diversify their sporting agenda, in the interests of the hounds alone, if only to have the canine ingredients of a rebirth one day, should field sports regain legal acceptance. To neglect the best interests of the dogs would be shameful. Positive thinking is called for, not intellectual collapse.

Throughout our social history as a nation, changing attitudes have influenced our use of dogs in the name of sport. Barbaric activities like badger, bear and bull-baiting, rat-killing competitions and dog-fighting contests have rightly been outlawed. Nevertheless, we still prize and perpetuate that one-time canine gladiator, the Bull Terrier, even if some legislators retain the view that once a fighter always a fighter. Bull Terrier fanciers need reminding that their dogs were sporting dogs in the field long before they were used in the pits. They should perpetuate their breed as a sporting terrier not as a role-less gladiator; a working test could so easily be devised to retain their sporting spirit. The spirit behind the trail-hound and Whippet racing, the Bloodhound packs which hunt a human trail, lure-chasing with Irish Wolfhounds and even nocturnal rat-catching in a maggot-factory, as the late Brian Plummer recommended, provides such encouragement for the future of sporting dogs. Perhaps, sadly, the single-issue lobbyists have them too in their sights.

Just over a hundred years ago, the great Bloodhound breeder, Edwin Brough, recorded: "The greatest benefactor to the ancient race (i.e. the Bloodhound) is the man who breeds intelligently, and supports both trials and shows, but there will always be people who are unable to devote time to both, and the trialer should remember that he will always be greatly indebted to the showman, and the showman should bear in mind that he owes the excuse for his existence to the trialer...their conception of the ideal hound should be the same." These are wise words from a gifted breeder; without field use many breeds lose the functional anatomy essential to sporting success. As fewer and fewer dog breeders take part in activities involving field sports, the functional aspect of their breed's phenotype can be lost sight of, and that is not good for any breed.

No sporting dog can triumph in the field without the physique needed for the sport concerned; as country sports are curtailed the challenge is to retain the working model not the prettiest one. The best dog show judges retain a concept of a breed's purpose in the ring; their critiques sometimes make disturbing reading. One recent critique from a Lakeland Terrier show made the comment that it should be the fox that runs away from the Lakeland, not the other way round! The Glen of Imaal Terrier judge at Crufts in 2003 found..."quite a few weak jaws and that would never do in my view for what they were originally bred for." At Crufts in 2001, the Bedlington Terrier judge reported "some lacked the bone and substance required in a working terrier." The 2009 Crufts judge remarked on Sealyhams: “Rear movement was a major concern to say the least.” And the Fox Terrier judge reported: “I was disappointed to see so many heavy heads…Movement was also bad in a lot of cases.” The Parson Russell judge commented: “Poor movement is still very much in evidence, with plaiting, paddling and a general lack of coordination.” The Irish Terrier judge concluded: “Movement in general was disappointing, looseness in front and lack of drive behind…” The Cairn Terrier judge was concerned that some males had very poor heads and heavy bone, expressing worry over the lack of good quality stud dogs. The Border Terrier judge stated: “Shoulders still need attention with many severely lacking layback, and, of more concern some foreleg assemblies are placed too far forward, so forechests are vanishing. This produces flashiness but it is wrong.” A year earlier, the Fox Terrier judge reported: “The quality of exhibits in males was disappointing.” It is extremely worrying that our top dog show should reveal such flaws in sporting terriers. Flawed pedigree terriers still cost a great deal to buy and even more to treat.

Dog lovers who pay £500 for a pedigree terrier pup and expect it to hide its sporting instincts and behave like a Toy breed are not engaging their brains. Terriers have an instinct to dig, to explore drains, to hunt small furry creatures and to display a combative nature. If you want a happier terrier, you need to be conscious of their innate yearnings, their inherited longings. Bored frustrated terriers can end up digging where you just don’t want them to, expending pent-up energy by chasing your neighbour’s cat and barking, just to relieve tension. Let them hunt a hedgerow, explore a shrubbery, race around the park – be active! You’ll have a happier terrier as a direct result – and almost certainly, a happier life. Terriers are essentially sporting dogs; they deserve our empathy. .jpg)

For a nation which has given the world a score of distinguished sporting terrier breeds, many of them preferred to the overseas native breeds on sheer merit, we must now work to ensure that all the dedicated work of our forefathers is not thrown away. I have long campaigned for terriers that are fit for their time-honoured function; if we do not respect their origins we will destroy many long-established much-admired terrier breeds, not just by neglect or indifference but from being arrogant enough to attempt their redesign on false criteria. Terriers do not need ground-hugging coats, heads like boot-boxes or a front assembly which denies them forward reach. Their locomotion should not be so impaired that they end up moving like canine millipedes. They should not ‘carry a leg’, as so many Jack Russells do, because of knee problems. The Bull Terrier does not deserve to be the only breed of dog with a rugger-ball for a head. The Staffordshire Bull Terrier does not deserve to be proscribed in countries abroad because its famed tenacity. The Dandie Dinmont’s topknot should not be more valued than a functional anatomy. The Fox Terrier deserves to be put back to work. The terrier breeds are very much Britain’s contribution to the canine world. Here’s to a long life for our revered breeds of terrier.

“Perhaps there is no breed of dogs which attach themselves so strongly to man as the terrier. They are his companions in his walks, and their activity and high spirit enable them to keep up with a horse through a long day’s journey. Their fidelity to their master is unbounded, and their affection for him unconquerable.”

From Anecdotes of Dogs by Edward Jesse, Henry Bohn, 1858.

“A Terrier forms the most lively companion one could possibly possess. He is all life, dash, pluck and hunt; and will make more fun for himself and you out of a short country walk than a dog of any other breed would in a week.”

From Training Dogs by ‘Bach’, The Stock-Keeper, 1896.

“Many a man will tell you that his pipe has solaced many a lonely hour and pulled him through many a rough time. I have known a Terrier act as an anodyne where a boisterously cheerful companion would have been a bore. To bachelors, to sufferers from the ‘blues’, if they do not smoke, then I recommend a Terrier – both go well together…as a rule they educate themselves in companionable habits…”

From Breaking and Training Dogs by ‘Pathfinder’ and Hugh Dalziel, The Bazaar, 1906.

“The Terriers are among the finest of all our dogs. They are strong, alert, inquisitive and courageous, friendly and playful but withal excellent workers. They are endowed with a degree of hardiness seldom encountered in dogs of other kinds, and they have a surprising ability to withstand disease. Asleep or awake, they are alert to unusual sounds and commendably suspicious of strangers. Their inherent curiosity bespeaks their intelligence, and their naturally happy temperament denotes their very joy in living.”

From The Book of all Terriers by John T Marvin, Howell Book House, 1971.