485 Speaking with one Voice

SITTING AT THE HEAD OF THE TABLE

by David Hancock

Last year I was visiting a national dog show when I bumped into someone well-known in the pedigree dog world as an owner/exhibitor, writer and judge. "Fancy seeing you at a dog show" he said, a little sarcastically, aware of my sustained critical writing over many years on such aspects as failures in the stewardship of our pedigree dog scene and the lamentable lack of soundness in many contemporary breeds. I hadn't the heart to tell him that I started attending dog shows before he was born.

Last year I was visiting a national dog show when I bumped into someone well-known in the pedigree dog world as an owner/exhibitor, writer and judge. "Fancy seeing you at a dog show" he said, a little sarcastically, aware of my sustained critical writing over many years on such aspects as failures in the stewardship of our pedigree dog scene and the lamentable lack of soundness in many contemporary breeds. I hadn't the heart to tell him that I started attending dog shows before he was born.

A few months later I was judging the retriever tests at a country fair when I mentioned to a competitor over lunch that I had seen some good dogs from his breed at Crufts that year. "My God!" he exclaimed, almost with a snarl, "you don't waste your time there, do you?" A week later I was scanning one of the weekly dog papers when my eye caught a piece about lurcher and working terrier shows, pouring scorn on the judging technique used in them and calling the whole business a meaningless charade. When summer came it was not pleasing to hear spiteful comments from pedigree dog exhibitors about the mongrel entry at our local village fete's dog show.

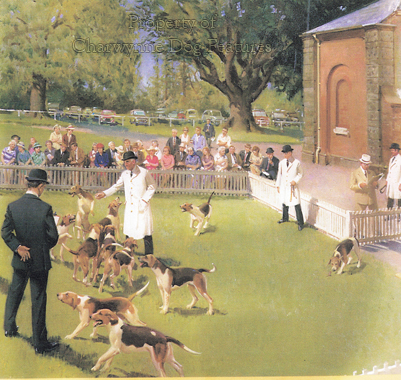

My interest in dogs takes me to sheepdog trials, working tests, hound shows, conformation dog shows, lurcher and terrier shows, seminars and society meetings. In each of these activities, I find well-intentioned people striving to contribute something towards either better dogs or the betterment of dogs. But each specialist in his field can be unaware of the contribution, potential or actual, of another. I learned more about assessing canine movement from houndshow judges than anywhere else. I learned more about communicating with dogs from shepherds than from gamekeepers. I hear more nonsense talked by well-educated dog fanciers than by lurcher and terrier devotees who sometimes have had very little formal education. But, I believe I am better informed from having listened to them all.

These are difficult days in dogdom. When I was young, Dangerous Dog Acts, docking and dodgy hips were not the dilemmas of the day. Congenital and inheritable diseases were not common topics of conversation in most breeds. But, no breeder then seemed to want to produce dogs with banana backs, excessively heavy coats, ruggerball shaped heads, questionable temperaments, exaggerated sickle hocks or string their dogs up on a choke cord in the show ring. A different foreign breed wasn't introduced every few months with a hyperbolised ancestry and questionable provenance. I have enormous respect for the pedigree dog breeders I learned from in the 1950s. So many of the gundog fanciers then worked their dogs. Many of the judges also judged horses and knew about movement. There seemed to be closer links between the 'flags' and the field. When I worked as a kennel boy for my local vet, he acknowledged only too readily the knowledge and skill of the dog breeders he served.

What is always needed when animals are used by man is an authoritative, thoroughly responsible, highly-motivated, totally dedicated patron at the head of the group of individuals involved. Sadly, the excesses of human conduct demand high-minded stewardship, morally-directed guardianship, especially where vulnerable animals like dogs are subject to human (or inhuman) whim. The domestic dog, purebred or mongrel, deserves a body to safeguard its best interests. What we have long needed is a club, a national club, set up by like-minded dog fanciers, to promote the best interests of dogs, whether they are used to demonstrate correctness of conformation in the show ring, functional prowess in the field or merely provide companionship to individuals or families. But do we have such an all-embracing high-minded national club?

Such a club would need to be London-based, so that it would be well placed both to influence national events and politicians, when the need arose. This club would be a charity, in spirit as well as in status, selflessly using its good offices to bring together to a common purpose: sportsmen and shepherds, vets and canine rescue charities, guidedogs and gundogs, lurchermen and working terrier fanciers, houndshow supporters and dog show devotees, agility and obedience groups, the sledders and the trackers. Above all else, this club would be able to speak with one voice -- the voice which the dogs themselves cannot make heard.

But what does human experience tell us to beware of in such an organisation? Firstly it must never become more of a self-regarding club than a selfless charitable guardian. Secondly the interests of the members must always come second to the needs of dogs. Thirdly it must never ever become a victim of its own internal systems, its innate bureaucracy. Its sole purpose must not be self-justification but speaking up for and protecting the best interests of dogs. The improvement of dogs by itself is too narrow a remit. But fourthly and perhaps most importantly it must perpetually remind itself of its guardian role, its moral foundation. Do we yet have such a body? Who truly sits at the head of this table?