429B Collie blood

THE VALUE OF COLLIE BLOOD

by David Hancock

Most lurcher breeders have long accepted the value of the blood of the collie in their stock; it could be argued that to qualify as a genuine lurcher the involvement of collie blood is essential. Twenty years ago, I had two working sheepdogs, i.e. unregistered Border Collies, with distinct sporting dog skills. The bitch was a natural setter; she never once gave a false point. The male dog was a remarkable marker and accomplished retriever, with a soft mouth and a willingness to go through any sort of cover. Their eagerness to work was commendable; their obedience constant; their astuteness remarkable. They did of course lack the sheer style of specialist gundogs but a more skilful trainer/handler than I could have developed them to a high standard. This combination of biddableness, cleverness and an unquenchable desire to work has led to the use of collies in a wide variety of ways in the sporting field.

Most lurcher breeders have long accepted the value of the blood of the collie in their stock; it could be argued that to qualify as a genuine lurcher the involvement of collie blood is essential. Twenty years ago, I had two working sheepdogs, i.e. unregistered Border Collies, with distinct sporting dog skills. The bitch was a natural setter; she never once gave a false point. The male dog was a remarkable marker and accomplished retriever, with a soft mouth and a willingness to go through any sort of cover. Their eagerness to work was commendable; their obedience constant; their astuteness remarkable. They did of course lack the sheer style of specialist gundogs but a more skilful trainer/handler than I could have developed them to a high standard. This combination of biddableness, cleverness and an unquenchable desire to work has led to the use of collies in a wide variety of ways in the sporting field.

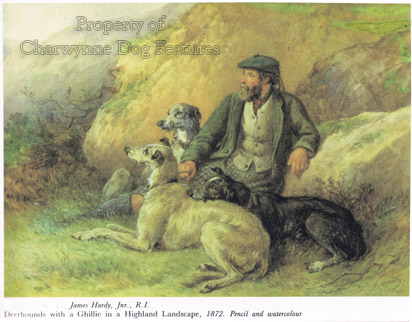

In his book The Scottish Deerhound of 1892, Weston Bell summarised a report from the various deer-stalking estates of that time which covered the use of dogs on them. The extracts he prints are illuminating: Achanault Deer Forest - No deerhound ever used, Auchnashellach, collie breed - good-nosed tracker. Balmoral Deer Forest - Very seldom do we use the staghounds--only keep them for breeding with the collie. Inverwick Forest - Very few gentlemen use deerhounds now-a-days in the forest--only the half-bred dogs, between the collie and retriever. Fairley Deer Forest - One collie in use now. One formerly. Deerhounds are not used in any deer forest that I know of in the north of Scotland. The best dog I ever saw for tracking a wounded stag was a cross between a retriever and a pure collie. Collie dogs, when trained young, turn out excellent trackers. Inchgrundle - Collie dogs have been chiefly used here for deer-stalking during the last twenty years. We generally find the collie more useful than the staghound.

The widespread use of the collie and the tributes paid to its prowess is astonishing and many other estates stressed their value and sporting skills: Braemore Deer Forest - I consider a good collie as far superior to any other kind of dog for a wounded deer. Aviemore Deer Forest - Three collies are at present in use...Properly-trained sheep dogs are the best. Mamore Forest - For tracking deer I think no dog so good as a good collie. Conaglen - We use sheepdogs here--they are more obedient and have more sense than the others. Rothiemurchus Deer Forest - Good tracking collies are the best for deerstalking. Glenartney - Good collies are the best I ever saw. Twenty other estates used collies for deerstalking.

Three estates used a collie-deerhound cross, one used a setter-collie cross and another chiefly used 'a collie of the grey shaggy breed', the beardie type. These extensive tributes to collie blood came from men who worked in the most testing country, in the most trying weather conditions and on a quarry never easy to stalk. The role demanded dogs that were hardy, had great stamina, immense perseverance and responded to commands often over some distance. There was not one mention in this wide-ranging estate survey of Bloodhounds, famous for their noses. The humble collie was the favoured dog. The retriever-collie cross came next. The collie-deerhound cross was clearly used in Deerhound lines, before Deerhound to Deerhound breeding was restored.

The collie-setter cross was allegedly used by the Duke of Gordon in the development of his breed of setters. SE Shirley, the Flat-coat pioneer, bred three of the most famous ancestors of the show collie - from an Irish Setter-collie cross. There is a distinct collie-look to many setters portrayed by artists in the nineteenth century. Iris Coombe, in her book 'Herding Dogs' relates how French sportsmen took their Brittanies to Scottish sporting estates and were so impressed by the cleverness of the local collies that they mated their dogs to them. They would have been seeking intelligence, trainability and responsiveness. Around 1826, the Marquis of Huntley angered the setter owners using Findhorn by utilising the clever collie of a local gamekeeper/shepherd as a sire for his setters. He put brains before beauty and got much abuse for it.

In his 'The Dog' of 1887, the celebrated writer 'Stonehenge' observed "When the lurcher is bred from the rough Scotch greyhound and the collie, or even the English sheep-dog, he is a very handsome dog, and even more so than either of his progenitors when pure...A poacher possessing such an animal seldom keeps him long, every keeper being on the look-out, and putting a charge of shot into him on the first opportunity." He went on to state that poachers made great efforts to avoid their lurchers looking like just that, to avoid being shot. But it has to be said that another reason, down the years, for antipathy towards collie cross lurchers in country areas, quite apart from poaching, is that the collie blood can contribute to an undesired canine criminal interest in mutton!

Ted Walsh, in his 'Lurchers and Longdogs' states that to create his sort of lurcher, he would start with two collie bitches, mate one to a Greyhound and the other to a Deerhound. The resultant pups would be fully tested and then culled, the survivors being inter-bred. The progeny of this mating would then be put back to a coursing Greyhound. This would have given him a preponderance of Greyhound blood but a fair input of collie blood too. It is absurd to declare precise percentages in products of mixed blood, genes work at random, not mathematically. Old lurcher breeders tended to put sagacity ahead of raw speed. The sighthound breeds are not renowned for their obedience or their brains; collies are.

Old lurcher breeders too prized the blood of the Smithfield collie, a type fast disappearing from the lurcher scene, in numbers at least. The leggy hairy Smithfield sheepdog has never been conserved here as such, but in Tasmania, Graham Rigby has some splendid specimens. Just as the Australian stumpy-tailed cattle dog is a descendant of the dogs once common in Cumberland, and still are so in the Black Mountain area near Hereford, these Tasmanian dogs originated here. Graham has had the breed for over twenty years. The first Smithfields to go to Australia were called black bobtails, big rough-coated square-bodied dogs, with heads like wedges, a white frill round the neck and 'saddleflap' ears. Graham is not a lurcher man, but any lurcher breeder seeking this blood, might find the expense of obtaining his stock worth every penny.

In his 'Hunters All' of 1986, Brian Plummer paid tribute to the collie lurchers of the likes of my namesake and Phil Lloyd. David's publication 'Lambourn' of some twenty years ago contains the best collection of collie lurcher photos I have ever seen, well worth a study. What you will see there is not a type but a variety of types, depending on the mix. Once lurchers start looking like a breed, then there's a contradiction in the making. The collie cross isn't meant to be the source of a distinct type, but evidence of an infusion of brains, biddability and a strong desire to work.edience or their brains; collies are.

Old lurcher breeders too prized the blood of the Smithfield collie, a type fast disappearing from the lurcher scene, in numbers at least. The leggy hairy Smithfield sheepdog has never been conserved here as such, but in Tasmania, Graham Rigby has some splendid specimens. Just as the Australian stumpy-tailed cattle dog is a descendant of the dogs once common in Cumberland, and still are so in the Black Mountain area near Hereford, these Tasmanian dogs originated here. Graham has had the breed for over twenty years. The first Smithfields to go to Australia were called black bobtails, big rough-coated square-bodied dogs, with heads like wedges, a white frill round the neck and 'saddleflap' ears. Graham is not a lurcher man, but any lurcher breeder seeking this blood, might find the expense of obtaining his stock worth every penny.

In his 'Hunters All' of 1986, Brian Plummer paid tribute to the collie lurchers of my namesake and Phil Lloyd. David's publication 'Lambourn' of some twenty years ago contains some of the best collie lurcher photos I have ever seen, well worth a study. What you see there is not a flashy show poseur but a functional creature bred for work. They remind me of the clever collie lurchers worked by the gypsies near my boyhood home. These dogs were trained to catch game at first and last light, hide it, and then retrieve it during darkness. I don't recall any of their owners being prosecuted for poaching. These gypsies only bred from their own stock.

Of course, you can get brainless collies, and long-backed short-bodied ones, leading to weak loins, a bad feature in a lurcher, and sometimes a lack of lung-room too; not good in a running dog. In addition, some collies are just too hyper-active to be valuable sporting dogs. Selection of breeding stock will always be the key to the successful production of lurchers, not the mix of ingredients. The dogs favoured for use in the Scottish deer forests were not valued because they were collies or collie crosses, but because they were outstanding dogs. If you want a dog with brains, biddability and a zeal for work, the collie offers all three. Every employer surely values a zeal for work!

"I think it is difficult to improve on the first cross Beardie/Border or Beardie/Border cross-bred. These I believe to be the best knock about, all round lurchers with ample speed, reasonable intelligence, excellent tractability and a really tough constitution. I am however open to comments about both half-bred and 3/4 collie 1/4 Greyhound hybrids."

Brian Plummer, Sporting News, 1989.

"The Lurcher proper is a cross between the Scotch Colley and the Greyhound. An average one will stand about three-fourths the height of the Greyhound. He is more strongly built than the latter dog, and heavier boned, yet lithe and supple withal; his whole conformation gives an impression of speed..."

Hugh Dalziel, 'British Dogs', Upcott Gill, 1888.