393 TRAILHOUNDS; Racing Scenthounds

THE TRAILHOUNDS: THE RACING SCENTHOUNDS

by David Hancock

Thirty years ago when walking in the Lake District, I saw in the valley below me what appeared to be a pack of Foxhounds in full flow. From a distance they looked like repeated splashes of milk as they poured in unison over stone walls and wire fences. But a closer examination, through strong fieldglasses, revealed that these hounds were not following either a visible quarry or ground scent; and they were not hunting as a pack. They were following air scent, with noses high, great pace and huge stamina, giant enthusiasm and considerable scenting skill. They were trail hounds racing along a laid scent-line at a speed one could only marvel at. This was a re-enaction of a medieval par force hunt but without a quarry.

Thirty years ago when walking in the Lake District, I saw in the valley below me what appeared to be a pack of Foxhounds in full flow. From a distance they looked like repeated splashes of milk as they poured in unison over stone walls and wire fences. But a closer examination, through strong fieldglasses, revealed that these hounds were not following either a visible quarry or ground scent; and they were not hunting as a pack. They were following air scent, with noses high, great pace and huge stamina, giant enthusiasm and considerable scenting skill. They were trail hounds racing along a laid scent-line at a speed one could only marvel at. This was a re-enaction of a medieval par force hunt but without a quarry.

As an increasingly urban society regards quarry hounds with a critical eye, hound-trailing, or hound racing as some prefer to call it, may provide an alternative outlet for redundant packhounds across Britain. The skills are not the same but it is one way of saving superb canine athletes from extinction. Walking in the Lake District is testing enough; racing over demanding country for mile after mile at high speed calls for remarkable staying-power, superb muscular condition, astounding determination, highly effective hearts and lungs, keen noses and more than efficient feet. These hounds are superlative middle-distance runners being used as steeple-chasers over long distance courses; quite outstanding sporting dogs.

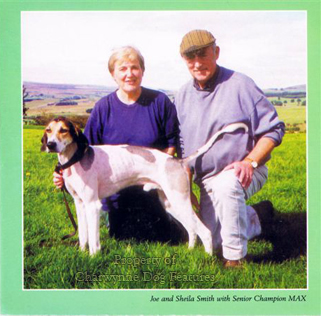

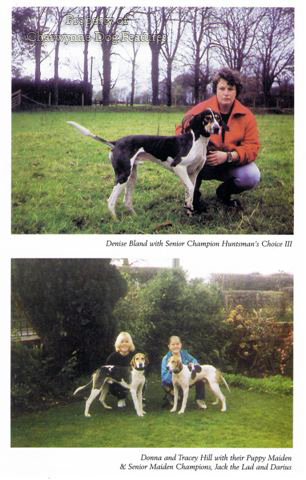

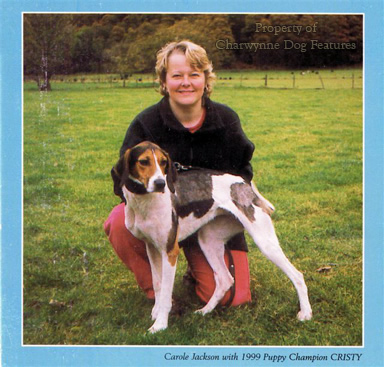

Superbly fit and skilfully bred, these hounds are much-loved pets too. Now justifying recognition as a distinct breed, they have been honed by performance rather than breeder-whim, emerging as sound unexaggerated functional animals yet still most attractive, as well as being genetically healthy and temperamentally sound. Those used to seeing soft-muscled over-weight exhibits in our KC-licensed show rings would regard these sleek superbly-conditioned hard-muscled hounds as being either skinny or underfed, such is the contemporary misappreciation of dog and dog-care. Hounds in exemplary condition for sports such as hunting, racing or coursing display the tuck-up, show of rib, svelte physique and pronounced muscle-tone which might lead some ignoramuses to report their owners to the RSPCA--and nowadays this body would probably find cause to investigate!

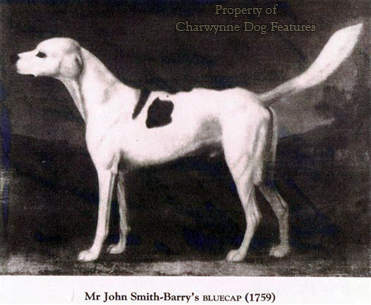

It has long been the tendency of man to test his hounds against those of others to trial their speed, stamina and scenting skill. This has led to the rag-dog races of the north-east, the racing Greyhound stadiums of the Western world and the 'match-race' competitions in the Foxhound fraternity of old. The latter produced the quite remarkable feat of 'Bluecap' (1759). Mr Smith-Barry's Bluecap and his daughter Wanton (1760) were run against Mr Meynell's couple from the Quorn pack. In 1762, a drag was laid over a four mile course on Newmarket racecorse. Bluecap won in a little more than eight minutes; 60 horses started with the four hounds; only 12 finished. This feat led to Bluecap being portrayed by the noted sporting artist John Sartorius, whose painting depicted a hound very much like a Fell Hound.

Hound-racing or trailing came from match-races conducted by MFHs of packs based in the Lake District, out of the same competitive ambitions as those of Smith-Barry and Meynell. Packs like the Blencathra, the Coniston, the Eskdale and Ennerdale, the Melbrake and the Ullswater by their very names give an idea of the country hunted over. The College Valley pack in Northumberland, once alleged to be the fastest pack in Britain, was of Fell type too, as demanded by their hill country. The 'Reminiscences of Joe Bowman and the Ullswater Foxhounds' of 1921 made this observation: "The development of the sport of hound trailing has spread the interest in the sport over a much wider area, and the rivalry between the northern and southern sections of the country is now very great. The north are claiming to produce a faster hound, a claim which was put to a practical test over an end-away trail from Wythburn to Ambleside. It justified the old opinion, "each hound to his own country" --the fell hounds to the scree, rock and bracken, and those trained in open country to the easier going ground."

The legendary Joe Bowman stated that Lord Lonsdale set the seal of popularity with his annual Lowther Castle trail, with an attractive meeting also at the Grisedale Hall trail near Hawkshead, where 'there is about a mile of straight. Here a splendid finish can be seen, when the scent is where it ought to be--breast high.' This illustrates the main difference between groundscent hounds like Bloodhounds, with their extreme persistence, nose to the ground style and placing of accurate precise tracking before pace, and the airscent hounds, the gazehounds, different from sighthounds, with their high heads, high pace and great drive. The steeplechase of the par force hunt using airscent hounds was long preferred in continental Europe. In Britain, 'hunting cunning' or the painstaking unravelling of ground scent eventually prevailed. This decided the development, or extinction, of our packs of hounds.

Out of the Fell packs and on to the trails came the fastest airscenters, with hounds from the Patterdale 'foxers' once coming first, second and third at the Grasmere Sports. In his 'Foxes, Foxhounds and Fox-hunting', Richard Clapham, a noted authority on hounds in northern England wrote: "Our fell hounds trace their origin back to the old Talbot tans, while later they acquired a certain infusion of pointer blood. The latter was introduced in order to make hounds carry their heads higher." He pointed out that white predominated in the Fell Hound's coat so that the hounds could be better seen by their foot followers. The infusion of Pointer blood to ensure a high head carriage may have had the added value of ensuring sound feet; sportsmen in South Africa and South America valued such an infusion because of this latter benefit.

Clapham described the Fell Hound in these words: "The general impression afforded by a fell hound is a complete antithesis of that provided by a hound of Peterborough type (i.e. standard houndshow type, DH). Instead of size, weight and power, we have lightness, activity, and pace, coupled with wonderful stamina..." In his 'Hounds of the World', Buchanan-Jardine described the Fell Hound as around 23" in height, with long, sloping shoulders, an elegant neck and a long lean head, usually with a slightly pointed muzzle. This reminds me of the French hound breed the Poitevin, which displays a similar head. Buchanan-Jardine interestingly observes in his book that "the foxhounds of the Cumberland Fells, no doubt owe the most to the old 'Chien blanc'..." i.e. the famous royal white hounds of France, which originated in a white hound given to Louis XI by the squire of Poitou, where the breed of Poitevin comes from.

The trail hound may have been founded on Fell Hound blood but since then has developed separately into its own distinctive type. In 1919 the blood of the Windemere Harrier 'Cracker' was introduced; in 1922 Lancashire Harrier blood was used and again, to greater effect, six years later when a Harrier sire 'Beware' was utilized, to produce a litter which subsequently proved dominant in the trail hound dynasty. (Trail hunts were held in the country covered by the Holcombe Hunt and the then Rochdale Harriers.) In the mid-20s a Pointer-Harrier cross, the bitch 'Gravity', was introduced and helped to found today's bloodlines. In the 1950s a Greyhound-Irish Setter cross was tried; then a West Country Harrier was tried (from the Dart Vale) and in 1962 a couple of Kerry Beagles also tried but none of these outsiders proved impressive in breeding terms.

It would be interesting to try a Saluki lurcher, bred for enhanced stamina, a Rampur Hound from India, the lighter-built American Foxhound, the Segugio from Italy or the podencos of the Mediterranean littoral, e.g. Portugal and Ibiza, as trail hounds. They possess the type of anatomy and the hunting instincts to succeed, the latter forming the basis of the trailing desire. One outstanding trail hound called 'Singwell' joined the local Foxhound packs in the winter and proved itself as a dual-purpose hound. Joe Bowman once wrote that: "Hunting of the aniseed and oil drag has been reduced nearly to a science by the fleet-footed hounds, but little doubt is entertained that the average hounds from the five Lakeland foxhound packs are little if any behind the drivers of the bloodless trail in point of speed, whilst in courage and stamina they will probably excel."

The sport of hound racing has long been highly competitive and a mainly working class pursuit. An early star, and first hound to win a hundred prizes, was 'Rattler', trained by an Ambleside cobbler but sadly poisoned, allegedly by a rival trainer. 'Rattler' had a son, 'Ruler', which was clever enough to run with the other hounds, without trailing its own line, then sprint in to triumph as an accomplished finisher. In contrast one of the fastest early hounds, a bitch called 'Ruby' was a poor finisher, often overtaken when in sight of the finishing line. Speed alone is not enough in these races.

Trail hounds race an 8-10 mile course over the most testing country in England and complete it in 25-45 minutes, the time range indicating the different terrain between each course set. Twenty years ago, a superb hound called 'Hartsop Magic' was the star of the trailing circuit. In 1985 she had 32 wins, a year later 26 and another 33 in 1987. Clapham claimed that hounds have been timed to do 15½ miles an hour over a course rising to 1,250 feet in the first mile and a half. The sport's governing body, the Hound Trailing Association, formed as long ago as 1906, can withhold prize money if a particular course is completed too quickly or too slowly. This may well be a shrewd method of reducing the chances of fixing a race.

This is a two hundred year old country sport, which I very much hope will survive, with the sustained support of local farmers and landowners, another two hundred. The morally vain can find little to criticise in this quite admirable canine activity. The hounds taking part however are still hounds; one once finished the course with a rabbit in its mouth and the ambitious outcross to a so-called Russian retriever produced a hound which prefered mutton to the thrill of the race! It is a well-regulated sport too and, with land being taken out of agricultural use and hunting with dogs under threat, one to be considered more widely than the Lakes.

I have nothing but the greatest admiration for the country people of Cumberland and Westmorland who have kept these hounds going over many years in such magnificent shape. As a lover of functional dogs, I congratulate them on their superb hounds and salute their achievements and efforts. I have twenty books on hounds which make no mention of trail hounds. But in the present political climate it is more likely that these hounds will survive than many others. The trail hounds registered with the Hound Trailing Association represent an important English native breed which deserves recognition as such. They are distinctive; they breed true to type; they have a long distinguished and recorded pedigree, and they are a huge credit to English dog breeders.

As a nation we are far too casual, even neglectful, about conserving our native breeds of dog and far too eager to import inferior foreign breeds. From the Kennel Club's lists have gone the English White Terrier and the Harrier. Sportsmen never bothered to protect the Llanidloes Setter, develop the Norfolk Retriever or preserve the English Water Spaniel. Sheep farmers failed to perpetuate the old sheepdog breeds: the Welsh Hillman, the Old Welsh Grey, the Blue Shag, the Smithfield Sheepdog and the Black and Tan. Of course some contemporary breeds carry their genes or perpetuate their type, but that has never been part of a planned conservation scheme.

The sporting dog is under unprecedented threat; there is a greater need now to safeguard our precious remaining breeds than ever before. The quarry hounds could disappear unless a function for them is found. Packs overseas may snap them up--as the renowned Dumfriesshire pack has been--for their prowess is acknowledged throughout the sporting world. But these are native British hounds, so very much part of our sporting heritage. We would be extremely foolish to leave their future development to foreign fanciers--or, even worse, politicians! Hound-racing may not suit those looking to admire the work of a pack or please mounted followers. But which do we prefer? Hound trailing...or nothing?