361A THE MAKE-UP OF THE SPORTING TERRIER

THE MAKE-UP OF THE SPORTING TERRIER

by David Hancock

“The Terrier instinct is bred into every Terrier worthy of the name. How many can recall the amazing aptitude their dog has for killing a stray rat that foolishly crosses its path? Others can remember the fight of one of their Terriers to finish a woodchuck. Still others have seen the rare conflict between a Terrier and an otter, a rugged battle but one in which Terrier spirit usually prevails. Thus, today’s Terrier, no matter what the breed, still carries in its veins the blood of conflict and the instinct to do the job. Let’s not change his conformation so that these traits and instincts cannot be used.”

“The Terrier instinct is bred into every Terrier worthy of the name. How many can recall the amazing aptitude their dog has for killing a stray rat that foolishly crosses its path? Others can remember the fight of one of their Terriers to finish a woodchuck. Still others have seen the rare conflict between a Terrier and an otter, a rugged battle but one in which Terrier spirit usually prevails. Thus, today’s Terrier, no matter what the breed, still carries in its veins the blood of conflict and the instinct to do the job. Let’s not change his conformation so that these traits and instincts cannot be used.”

John T Marvin, The Book of All Terriers, Howell Book House, New York, 1971.

Ugly little varmint or cute little canine fashion model? Couch potato or crouching tiger? Scarred canine miner or handsome reduced hound? What should a sporting terrier look like? Does its anatomy truly matter? Is its spirit more important? In his 'Sporting Terriers' of 1926, Pierce O'Conor wrote: "That the foxterrier of today is a great improvement, in so far as looks go, on his predecessors of forty or fifty years ago is beyond question, though whether he is better suited physically or morally for work underground is a matter of opinion". If O'Conor were alive today, I think he would strengthen those words even more and would not be a happy terrier-man.

In Field Sports magazine in 1949, in an article entitled The Hunt Terrier Man and His Dogs, old terrier-man Fred F Wood wrote of his kind: “There is also another attendant to the pack, the terrier man…then look at his little companions, maybe a couple or a couple and a half of terriers, not much to look at perhaps, the show terrier man might call them ugly little mongrels, but there is no mongrel about them, many of their pedigrees have been as carefully kept as those of the hounds, not for their appearance, but for their qualities. They have to be constructed of bone, wire and whip cord, and have coats that will keep out cold and wet and then on top of that be brave as lions, if they are to do the work they are called upon to do…so think of those little terriers…they will stay and fight their fox until he bolts or they are dug out, that requires pluck.” It was fear of their terriers losing their working anatomy, and especially their ‘pluck’, which steered working terrier enthusiasts away from the show ring.

In his book The Terrier’s Vocation of 1949, Geoffrey Sparrow writes: “Some years ago there was a wire haired dog at the Crawley and Horsham Kennels which was one of the best I ever saw; he had rather a shy way with him and couldn’t abide a lot of raucous halloaing, nor would he enter a hole unless he wanted to. The first time I saw him at work out hunting, they couldn’t get him to go at all and were just going to give it up when someone said: ‘There’s a heck of a noise underneath where I’m standing.’ Well, it was quite obvious he had waited his time and then gone into another hole, got up to his fox and was busy at him. At the beginning he looked abject, mean and utterly lacking in courage, showing how deceptive a dog may be.” I have had comparable experiences with infantry soldiers, especially countrymen; judgements made on outward appearances don’t count for much when the real tests come.

The key senses of a working terrier: sight, hearing and ‘feel’, or touch, matter very much to an earth-dog. The great American expert on dog behaviour, Clarence J Pfaffenberger, in his The New Knowledge of Dog Behavior of 1963, wrote: “A dog can hear much higher and lower sounds than a person can. His sense of smell has never been satisfactorily evaluated, but it is so superior that we do not yet know its workings. A dog’s eyes are different from ours. One very valuable quality is his ability to practically photograph motion. Where we might be aware that something moved, a dog will know just where it moved.” In this connection, it is worth noting the words of Dugald Macintyre in Field Sports magazine in 1949: “Terriers are smart dogs, and I had more than one which did remarkable feats. There was the West Highland White who, assisting farm collies to chivy the hares out of an oat-field which was in the process of being reaped – after some hares had escaped, lay down by the gate of the field, and so secured several. The collies could only see what was ‘before their noses’, but that terrier was a bit of a thinker. The same terrier could be lifted up in one’s arms to point out a distant hunting stoat, or to make him understand that he was to go to a bridge and cross it, to get to at the holt of an otter.” Terriers may lack height but we must never underestimate their ability to pick up movement far far better than we; it would be unwise too to play down their sheer canniness, as Macintyre indicates.

I believe that it is entirely fair to state that of all the types of dog ruined by the effects of the Kennel Club-approved show rings the Terrier Group has suffered the most. This is sad for a number of reasons: firstly, the Kennel Club was founded by sportsmen, with the Rev. John Russell an early member and Fox Terrier judge; secondly, the breeders of those terrier breeds recognised by the KC boast of the sporting ancestry of their dogs - and then dishonour it, and, thirdly, some quite admirable breeds of terrier have been degraded, even insulted, in this way. Discounting the Airedale, never an earth-dog more a hunting griffon, and farm dogs like the Kerry Blue and Wheaten Terriers, which were all-rounders rather than specialist terriers, all show terriers should only be called full champions if they have passed an underground test.

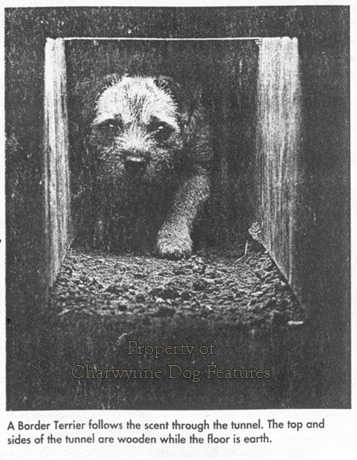

In the United States, they are shaming us by conducting such ‘gameness’ tests, ranging from 'Introduction to Quarry' and 'Junior Earthdog' to 'Senior Earthdog' and 'Master Earthdog'. Introduced by their kennel club, the AKC, in 1994, in the introduction test, the terrier (or working Dachshund) has two minutes to enter a ten foot tunnel, negotiate a 90 degree turn and 'work' (i.e. bay, growl, lunge or dig) the quarry (sometimes a caged rat) for 30 seconds. The American enthusiasts say that "you put a dog down the hole but you get a terrier out of it". In the master earthdog test, acting in a brace, a dog has to follow a 100 foot scent trail to a hole, which is intentionally a false one, investigate the false den without giving tongue, then navigate 30 feet of tunnel only 9 inches square, three 90 degree turns, a false exit, a constriction point and an obstacle.

The French have their clubs practising ‘la venerie sous terre’, working under licence on badger, fox and coypu using wire and smooth Fox Terriers, but also featuring Teckels, Fell type and smaller hunt terriers. They proudly parade at the French Game Fair at the chateau at Chambourd near Tours each year, with their gleaming spades and polished pick-axes, even badger-tongs. Writing in Countryman’s Weekly in November 2004, Jeremy Hobson stated: “It seems strange to have to visit France to see the best examples of working terriers. Long-legged smooth-coated Jack Russells are extremely popular and almost all conform to the likeness of ‘Trump’ (the terrier Russell bought from a milkman in 1819)…deep-chested, straight-legged and with powerful shoulders, a stud dog from one of these packs would, I feel, benefit many strains being bred in the UK today.”

Seventy years ago, Pierce O'Conor was advocating something similar. He described the French apparatus for trying terriers: a wooden conduit 7½" wide, sunk in the earth, with passing chambers, just over 50 feet long. Terrier-testing underground is so much more a basis for judging than any 'beauty show'. It tests, however artificially, the working instinct and character of the dog. It is both surprising and disappointing that at game fairs and country shows the underground testing of terriers isn't conducted. It would cost little to instal the equipment needed for such essential tests of terrier function. Come on, Game Fairs of Weston Park and Ragley Hall, set the pace!

But having heard the expression 'gamest of them' applied to early Sealyhams resurrects an old worry of mine. Having read of the method used by the celebrated Captain John Tucker-Edwardes to 'prove gameness' in the terriers he used when fashioning the Sealyham as a distinct breed, it has always appeared to me the perfect recipe for producing brainless canine psychopaths. I cannot understand his fame as a terrier-man if the stories about his 'selection tests' are true. Terriers which when not at work are expected to kill captive polecats are not likely to appeal to those terrier-men who also keep ferrets!

In his book Working Terriers of 1948, Dan Russell writes: “The very best terrier I have ever owned was one of these Border-Sealyhams. He weighed 15lbs and was immensely strong. For four seasons running he did his two days a week with hounds, during which time I dug eighty-three brace of foxes with him and he bolted goodness knows how many, twenty badgers and three otters; in all that time he sustained no injury beyond an odd nip or two and never missed one day’s hunting.” I have never heard a proper terrier-man admire a dog that was too hard. OT Price, a great terrier-man in his day, once stated: "Don't let your terrier get too hard. Remember that a terrier's job is to bay the fox not fight it." And, according to Dan Russell, "the hard dog is as big a nuisance as the coward. He spends half his working life in hospital." I am reminded of the story of the half-wit who returned a young terrier to its breeder as a 'waste of space' because it declined to slaughter a neighbour's tomcat which he had put into a barrel with his newly-acquired pup to 'see what it was made of '. The pup, which had been raised with farm cats in his barn birthplace, went on to prove himself as the bravest of dogs.

In an article in Hounds Magazine in 1987, that most knowledgeable of field sportsmen, who wrote under the nom-de-plume of ‘The Gaffer’, stated: “I have seen many big dogs shockingly scarred and marked simply because in a tight place they could not get back from the fox, thus they became very hard and are useless for bolting. Give me the smaller narrow terrier with brains and character that can get in a small place, stand back and make a lot of noise. Those are my sort! I have bred and worked them for the last fifty years and it always pleases me when there is a call for one of the ‘Gaffers’ little bitches.”

Writing in Field Sports magazine in June 1952, working terrier expert RR Stopford stated: “As time goes on you will know just what sort of noise he makes against different opponents. No dog fights mute, but some have the aggravating habit of baying at a rabbit when there is a fox or a badger in the same earth! For this reason many experienced diggers will not use their dogs for rabbiting, but provided you have not got a fool of a dog he will tend always to seek out the most dangerous opponent. A terrier that stays underground until he kills, or is physically exhausted, is a real nuisance and a danger to himself.”

Major Ollivant wrote that "...the terrier's pluck must not be the bravery of the Bull Terrier that goes in regardless of consequences, but the brave, fearless kind of pluck that knows its own danger, and yet has the grit to stay there." The relevance of degrees of aggression to build lies in the fact that if you use Bull Terrier blood to strengthen the head, you risk the production of a holy terror that could be a blessed nuisance! When I hear of working terrier-men utilising show dog blood to achieve a physical point, I recall the words of Geoffrey Sparrow on this subject: "...but then she had a working pedigree back to the nineties on both sides. The real blood must be there or the pups are sure to throw to soft lines."

Working terrier enthusiasts will never show great interest in precise measurements, exact proportions or wordy descriptions of anatomical features. But balance, symmetry, correct proportions and physical soundness really do affect function and therefore performance in a hunting animal. Terrier show judges may prefer to judge entirely by eye and experience, but is this enough? A seminar of sporting terrier judges to bring on the younger judges would surely be of value. It would be interesting to hear, at such a seminar, what terrier show judges' decisions are actually being based on: gut feeling, their own preferences, previous winners, knowledge of anatomy? I attend seminars run by the Sporting Lucas Terrier Club, in my role as breed advisor, and am always willing to argue my views at such an event, whether on conformation or colour.

In his piece in Field Sports magazine of June 1952, RR Stopford also wrote: “The weight for all types of work should not be more than sixteen pounds, and preferably about fourteen. Colour, looks and length of coat are personal considerations, but the more white there is the better, because a conspicuous colour has its advantages when shooting in thick cover. Another controversial point is the length of muzzle. A long nose is useful for ratting, but takes heavier punishment underground; moreover, it is but rarely accompanied by a strong wide jaw, so that, on the whole, we may say the shorter the better.” He would not like the head of today’s Fox Terrier, but it is of interest to see his high priority for the colour of his dogs’ coats.

Terrier-men have long held prejudices about the colour of their dogs’ coats. You only have to look at some terrier breeds to see that colour makes the breed: West Highland Whites, Kerry Blues and Plummer Terriers for example. In his insightful The Mind of the Dog of 1958, vet, exhibitor and sportsman RH Smythe wrote: “Conformation, physique and hair colour appear to exert less influence on temperament than these same features are believed to do in the case of humans. One cannot truthfully claim that black dogs are more sensible, more trustworthy or more lively than white dogs or vice versa. A Kerry Blue is usually vivacious and high-spirited, sometimes truculent; a blue Bedlington is often sensible and gentle in disposition. A red Irish terrier may exhibit the characteristics attributed to his countrymen, but a red Irish setter may be mild and law-abiding. Any differences are obviously associated with the breed rather than with the colour of the coat.” Being able to see a small bushing dog in close cover however may matter a great deal.

Coat texture seems to matter for some, not in its weatherproofing qualities, but in its association with stubbornness. In his under-rated The Understanding of a Dog of 1935, Lt Col GH Badcock, a highly experienced trainer of dogs, wrote: “Why should most smooth Fox-terriers be so much more biddable and easy to train and correct of faults than the wire-haired variety? There is a curious tenacity of purpose about these broken-haired breeds that makes them extraordinarily difficult to correct of faults…I have a larger percentage of failures with insubordinate wire-hairs than any other breed.” I would value ‘tenacity of purpose’ in a working terrier, but Badcock knew more about training dogs than I do! A writer with plenty of experience in training terriers, the late Brian Plummer, wrote in his Secrets of Dog Training of 1992: “Terriers, despite their small size, are sometimes far from easy to control. In addition to the fact that most terriers still retain a strong inclination to hunt any type of animal or bird whose scent crosses their paths, the majority are particularly eager to take offence from another dog…terriers do need a great deal of exercise to sublimate their working instincts.” A number of researches into defensive behaviour and pain sensitivity have revealed appreciable differences between breeds. Terriers were found notably, but hardly surprisingly in view of their role, very resistant to pain relative to other dogs. This demands more patient training so that a young terrier doesn’t actually perversely welcome ‘punishment’ but be guided by firm consistent direction and its desirable persistence retained.

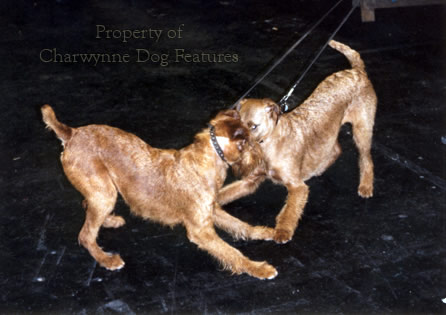

In his book Working Terriers, of 1948, Dan Russell wrote: “The real working terrier is usually very self-contained; he keeps himself to himself and does not fight with other dogs unless in self-defence. I always think this is because he knows he gets into enough trouble in his life without going to look for it. In any event, the quarrelsome brute is generally a coward. Watch your dog at the meet. You will have him on a lead, but hounds will come around and sniff at him. If he is of the right sort he will stand his ground quite quietly, although he may give a warning growl when hounds crowd him or get too familiar, but he will show no signs of fright or panic.” These are wise words; sporting terriers need to be self-confident, steadfast and with stable temperaments. All show and no ‘go’ is of no value whatsoever to a sporting dog.

Genetic predispositions in breeds of dog are rooted in their function. The American psychologist Stanley Coren wrote a book about matching breeds to human personalities. He listed dogs in seven categories according to their psychological make-up. The Airedale Terrier was the only terrier breed listed as independent, perhaps its hound blood manifesting itself. He listed as ‘self-confident’ breeds: Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Yorkshire and Fox Terriers, but would not have known of many working types of unregistered terrier breeds. He listed the Skye Terrier quite separately under the ‘steadfast’ types, perhaps a reflection of their long breeding for show ring boredom!

It is important to keep in mind that a dog is not just like one of many other animals, but very much a creature of humans, an artificial animal in many ways. It is an animal which has been shaped and fashioned in its behaviour and appearance to suit human desires. With the possible exception of the domestic cat, a dog is probably better equipped mentally than any of the other domesticated animals, yet its perception of other living things and objects around it is restricted by the conditions and emotions of the moment. It is a modern cliché that dogs are merely creatures ruled by instinct. In reality, as compared with the lesser animals that do function mainly as a consequence of instinctive action, the dog seems to possess rather a limited number of instincts which cause it to operate. A number of psychologists and behaviourists have commented on this.

In his enlightening book Understanding Your Dog, published by Blond Briggs in 1972, the distinguished veterinary scientist Michael W Fox writes: “The inheritance of behavior and temperament is complex, for the characteristics of a breed comprise a combination of several independently inherited traits which are modified by genetic factors. No trait is inherited as such; genetic factors are transmitted by inheritance, but the traits themselves are modified by interacting genetic and environmental factors. Training and early experience greatly influence these traits, and it is the selection of traits which facilitate easier training to perform particular tasks that differentiates one breed from another and individuals within the breed.” Well-selected breeding stock is more likely to produce progeny which can assimilate training and respond to experiences. Genes are facilitators not directors.

The pioneering animal behaviourist Dr Konrad Lorenz has coined the phrase ‘instinct-training conditioning’, in which an innate, or instinctual, predisposition to respond is reinforced or shaped by experience. Following a trail and discriminating it from others, and the ability to catch, kill and even consume prey efficiently, exemplify this. The innate predisposition to follow enticing scent and to pursue small moving objects is seen in all young pups, as they explore their environment and ‘play-hunt’. These activities expose them to experiences from which they benefit by instigating and improving their ability to track and hunt. Early learning enormously assists the young terrier to ‘cash-in’ on its genes. Early experiences can be lasting ones, for good or bad. The making of a terrier comes from such early learning; the make-up of the terrier allows it to benefit the most.

Terrier breeders should always be seeking ‘the whole dog’, not pursuing one feature obsessively and excessively whilst accepting others not entirely beneficial. As Darley Matheson records in his 'Terriers' of 1922: "Quality of front is greatly sought after by breeders, but a beautiful front ought not to be allowed to overshadow poor hindquarters". This over-emphasis of one physical feature to the detriment of others is a curse. Some terriers are judged on their 'spannable thorax' whilst their stuffy necks, weak loins, short bodies and thin feet are overlooked. Some tolerate frenetically barking terriers, furiously striving to attack any dog within reach, mistaking such character weakness as terrier-temperament. The sound production of a terrier is about the whole dog, never the blinkered obsessive seeking of perfection in one area or the blind overlooking of undesirable traits. There is one area however which should always be emphasised in sporting terriers, and it is in their spirit not their build; without 'attitude' no working dog is ever going to succeed. The character of a terrier is everything.

“Forbidden fruit is always sweetest, and breeders of show terriers are never tired of dinning into one’s ears that their dogs are workers as well, and bred on the right lines for make and shape, but they lose sight of the fact that while they have been breeding them for straightness, they have acquired a giraffe-like length of leg, and while breeding them for appearance and show-points they have lost all their individuality, intelligence and stamina.”

Arthur Blake Heinemann, writing on Hunt Terriers in The Field, October, 1912.

“These old working terriers were tough and strong. They had to be because their daily life consisted of facing cornered animals which they had to kill or bolt. The fighting underground was savage and the terrier was expected to succeed or die – and many of them did – either through bites or by being trapped under the earth. Courage or ‘gameness’ was the quality most prized by the terrier breeders and cowardly dogs were very rare indeed because a terrier showing the slightest trace of fear was quickly destroyed and never used for breeding. The old types were also swift and some were known to have covered over six miles in thirty minutes – a very good time over rough country by a comparatively short-legged animal.”

CGE Wimhurst, writing in his The Book of Terriers, Muller, 1968.

“But now for the terriers, a most important and indispensable adjunct to a pack of otter hounds; for on every occasion where strong holts or underground drains are met with, on them it will depend whether a trail is to end in a find or not. The process of ejectment, generally a bloody one in close quarters, it is their duty to serve. The terrier, therefore, should be hard, wiry, and by no means too big in size; otherwise he will not only be able to work a narrow drain, but by scraping back the earth to get at the otter, he will dam the water behind him, and so, if not rescued, be drowned.”

The Duke of Beaufort in his Hunting, Longmans, 1894.