361 Hounds in USA

HOUNDWORK IN AMERICA

by David Hancock

The hounds developed in the United States are largely unknown to hound fanciers in Britain. This is partly because they are mostly working types, not recognised by the American Kennel Club, but also because the distinctive hound breeds there have usually been under-rated by the working hound fraternity here. It is true too that American styles of hunting, allied with different quarry, saw the development of hounds with a quite different purpose from ours. The Americans too use some of our breeds in the hunting field when we have long since failed to do so. Airedales, sometimes weighing up to 90lbs, have a hunting role there which perpetuates the sporting instincts of this admirable breed.

The hounds developed in the United States are largely unknown to hound fanciers in Britain. This is partly because they are mostly working types, not recognised by the American Kennel Club, but also because the distinctive hound breeds there have usually been under-rated by the working hound fraternity here. It is true too that American styles of hunting, allied with different quarry, saw the development of hounds with a quite different purpose from ours. The Americans too use some of our breeds in the hunting field when we have long since failed to do so. Airedales, sometimes weighing up to 90lbs, have a hunting role there which perpetuates the sporting instincts of this admirable breed.

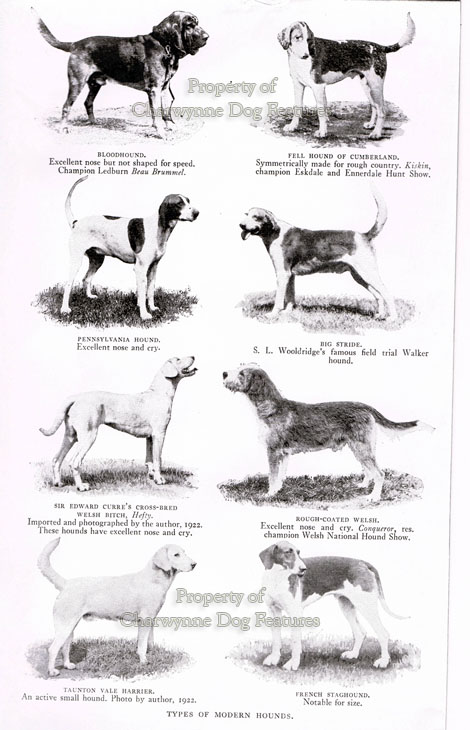

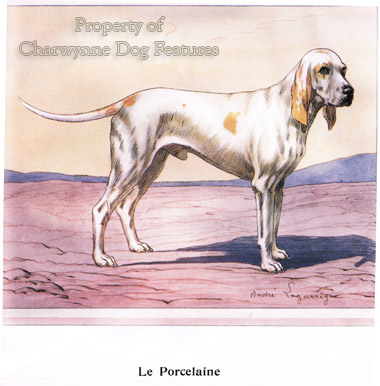

The American packhounds are easily outnumbered by the ad hoc or 'bobbery' packs kept by families or individuals there, with the hounds bearing colourful names: Big 'n Blue (American Blue Gascon Hound), Black Mouth Cur, Bluetick Coonhound, Treeing Tennessee Brindle, Redbone Coonhound, Redtick Coonhound and the Plott Hound from the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. The Black and Tan Coonhound and the American Foxhound are recognised breeds, with the latter having three strains in the South: the Walkers, the Triggs and the Julys or July-Birdsongs. All of these breed true to type, excel in the hunting field and perpetuate the blood of many European scenthound breeds, mainly French and English. From the Louisiana Bayou, the Ozark Mountains and other remote areas came French 'Staghounds' or Blue Gascons, with the Bluetick Coonhound claiming the blood of the French hound breed of Porcelaine.

The more orthodox formed packs in the United States are not short of catchy names either. There is the Why Worry Hunt in South Carolina, with many lemon and white hounds, the Plum Run hounds in Pennsylvania, with their tricolours, the Hidden Meadow Beagles also in Pennsylvania and the Sandanoma Hare-hounds in New York State, with their sturdy Basset Hounds. The Aitken hounds in South Carolina feature some strapping hounds, a number of them mainly white. If anti-hunting legislation is passed here, there could be a whole new emphasis on sporting tourism over there. There are close links between the hunting communities of Britain and America.

The importation of hounds into America has gone on for well over five hundred years. One historian described an embarkation for America in 1539 of De Soto "with his Portuguese in shining armour, his horses, hounds, and hogs". These hounds were however hunting mastiffs for use on native Indians. From England, the Cavalier, Robert Brooke sailed for America in 1650, taking 40 of his family - and his pack of hounds. These hounds are behind the Trigg and Walker hounds and their descendants were followed by the Brooke family well into the 20th century. Dr Thomas Walker imported hounds from England into Virginia in 1742, using them to hunt buffalo, elk, bear, deer and even turkey!

In 1785, George Washington received 7 hounds from France, which were described as being 'of great size'. French hounds were imported into Louisiana in the late seventeenth century, of the Normandy breed - Franc Comptoise, known locally as Porcelaines. An importation from Ireland in 1830 had a major influence on the Henry, Birdsong (of Georgia) and Trigg (of Kentucky) strains. These are believed to be Kerry Beagles, 24", black and tan, red or black in colour. The Walker hounds were revitalised with English blood in the late 19th century. American hounds were bred solely for performance rather than on some model of physical perfection.

The greatly respected American hound expert, Joseph B Thomas, writing in 1937, made this penetrating observation: "The British are the greatest breeders of livestock the world has ever seen or probably ever will see. They breed their mares to the Winner of the Derby; they breed their greyhound bitches to the Winner of the Waterloo Cup; and yet they often breed their foxhound bitches to the Winner of the Peterborough Show (a houndshow for packhounds), which winner is judged by the artificial standards...without regard to what this same animal can do..." Breeders of pedigree sporting dogs, please note!

The British hound expert, Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, imported two couples of the best American Foxhounds and hunted with them for two seasons. He found that in our conditions they lacked stamina. They were more like our Fell hounds than the standard Foxhound. He reported that their shoulders were inclined to be rather upright and that they "gave tongue too freely". To the great credit of the American hound breeders however, they never subscribed to the astonishing and ill-informed desire for massive bone in their dogs, as our Edwardian Foxhound breeders most unwisely did. This era, described by one famous hound expert as the 'Shorthorn period', influenced some Mastiff, St Bernard and Bloodhound breeders here too - and sadly, still does.

The English Foxhound, the American Foxhound and the Black and Tan Coonhound all feature in American show rings. The latter is big handsome breed, the first 'cooner' to achieve American Kennel Club recognition and was allegedly developed from Virginia Foxhounds. It is interesting that its breed standard starts off with these words: "The Black and Tan Coonhound is first and fundamentally a working dog, a trail and tree hound, capable of withstanding the rigors of winter, the heat of summer and the difficult terrain over which he is called upon to work." If only the comparable standards of our pedigree scenthound breeds could feature such a clear, unambiguous and firm indication of their breed's purpose, value and priorities. The AKC breed standard for this coonhound has over 100 words covering its gait/movement. The KC breed standard of our nearest equivalent breed, the Bloodhound, contains only three words on gait/movement but over 230 words on the head/skull. It does not mention that the hound is expected to be able to work!

Now also recognised by the AKC is the highly respected Plott Hound. Preferred in brindle, weighing around 50lbs and standing over two feet at the withers, this hound breed is described in its breed standard as: noted for stamina, endurance, agility, determination and aggressiveness when hunting. The standard commendably states that too much bone is a fault, something I can find in no British breed standard, more's the pity. This breed has long been favoured for its courage, which has led to their use in jaguar hunts in the Mato Grosso to the bear hunts of North America. The latter often feature Airedale-hound crosses, Norwegian Elkhounds and local blends, backed by cold-nosed hounds such as Walker, Trigg, July, Redbones and Blueticks.

We may not approve of such hunting but it takes courage for any dog to approach a bear and that degree of courage is worth perpetuating. The Tahl-Tan Indians up in north-western British Columbia had their own specialist bear dog. They were black or black and white spitz dogs, around 15" high with a brush-like tail, held erect. The Tahltan Bear Dog had a fox-like yap and a coyote yodel; like wild dogs they came into season only once a year. The Indians used them to hunt black and grizzly bears and lynx. They hunted in the Scandinavian spitz dog style, barking furiously to bay their quarry and alert the approaching hunters to the prey. Once registered with the Canadian KC, the last recorded one being in 1948, this distinctive breed may well now be extinct, another loss to the gene pool of the domestic dog .

Two other distinctive breeds very much still with us are the strikingly-named Catahoula Leopard Dog of Louisiana and the handsome Black Mouth Cur of the southern states. Both these breeds will herd cattle, with breeders of the former preferring their dogs to be called a herding breed. But both have the classic phenotype of hounds, the type once called par force hounds in Europe (or gazehounds, before that word became mistakenly confused with sighthounds). The Black Mouth Cur resembles a stockier Rhodesian Ridgeback, without the ridge. It is a remarkably robust breed and worthy of consideration whenever an infusion of outside blood is desired in one of our native or imported breeds with a small gene pool. .jpg)

The Leopard Dog will never be confused with another breed, with its distinctive eyes and (usually) black-merle coat. Breeding merle dogs is not without its dangers but these are tough, resilient, long-lived dogs. They remind me of the black-merle lurchers bred here by my namesake, now famous in many countries for their field prowess. I see red-, grey- and black-merle lurchers at country shows and impressive dogs they are too. Noting its coat colour, some researchers have linked the Catahoula dog with dogs brought to the Americas by Spanish colonists, to be subsequently acquired by Indians and later by settlers.

I think this is fanciful, along with theories of French immigrants bringing herding dogs, similar to the Beauceron, with a harlequin coat, what the French call 'gris avec taches noires danoises'. But why not speculate on the blood of the Norwegian Dunker Hound too, with its breed-specific merle coat? Recessive genes carrying grey, red or black merle, blue ticking, red ticking and harlequin are present in a number of breeds. It would not be difficult, as our lurcher breeders have demonstrated, to find a gene combination which threw the distinctive coat colour favoured, and stabilize it in time. Any breed intentionally restricting itself to one coat colour only, for ever, is however depriving itself of the richer genetic diversity available outside that colour.

Some, no doubt the owners of red-tick or blue-tick hounds, will link the coat colour with certain traits of value in the field. In Britain, for example, the sportsman Sir Peter Farquhar found that the blue descendants of a hound named Carmarthen Nimrod '24 had better noses than the non-blue. In the greatly-respected Dumfriesshire Foxhound kennel the black hounds generally have appreciably more quality than those with more tan in their coats. It is interesting that the setter and scenthound coat colours have developed on parallel lines, whether it is red or blue tick, solid red, black and tan, lemon and white, red and white or black and white. This may be due to more than just sportsmens' preferences.

As in so many breeds, American hound breeds were developed by determined sportsmen, each seeking excellence in his field of hunting. Jonathan Plott left his native Germany in 1750, and went to America, with a few of his favourite boarhounds. He settled in the mountains of western North Carolina and initially used his hounds exclusively for bear hunting. He did not outcross for 30 years and bred what can be truly claimed to be a 'family breed', with an awesome reputation on bear and boar. Plott hounds have since been used on wolf, mountain lion, coyote, wildcat and deer. There has been speculation that his original hounds were of the Hanover Scenthound type and rumours of outcrosses more recently to Airedales and Black and Tan Coonhounds.

Colonel Haiden C Trigg, who also gave his name to a famous pack of hounds, developed his 'long-eared, deep-toned, rat-tailed, black and tan Virginia hounds' in the mid 19th century. He obtained his stock from noted sportsmen such as George Birdsong, Dr TY Henry and the packs created by Walker and Maupin. The foundation of the Walker line was laid by two English importations and a hound literally stolen from a pack whilst actually on the chase in the mountains of Tennessee. One of Maupin's friends noted the outstanding performance of a local hunting pack--and immediately stole one of the hounds taking part! In due course the Trigg hounds became the most widely used in American fox hunting.

George Birdsong's hounds were probably the foundation stock of the Redbone strain, solid-red treeing and trailing hounds. Claims have been made for a Scottish and an Irish origin for these hounds, with their name being linked with Peter Redbone, a Tennessee promoter of this strain. Both the Red-tick and the Blue-tick Coonhounds have been called 'English' at times in their development and it is clear that the British Isles has played a major role in the creation of all these American hounds, with the exception of the Plott hound. But, wherever their origin and however widely spread their ancestors, these are valuable proficient hounds, created a long way away by gifted breeders; they deserve conservation, and our interest.