343 BREEDING A REAL SIGHTHOUND

BREEDING A REAL SIGHTHOUND

by David Hancock

“The tall, slender hounds that appear on the rock carvings of North Africa, Egypt, Nubia and Arabia all belong to the family of greyhounds. They are all bred for the chase and are an exclusive though geographically widely distributed group. They are also very ancient, indicating that their selection for speed, stamina and the ability to thrive in hot climates, which made them the companions of the early hunters, began a very long time ago.”

“The tall, slender hounds that appear on the rock carvings of North Africa, Egypt, Nubia and Arabia all belong to the family of greyhounds. They are all bred for the chase and are an exclusive though geographically widely distributed group. They are also very ancient, indicating that their selection for speed, stamina and the ability to thrive in hot climates, which made them the companions of the early hunters, began a very long time ago.”

Swifter than the Arrow by Michael Rice, Taurus, 2006.

Revealed in Performance

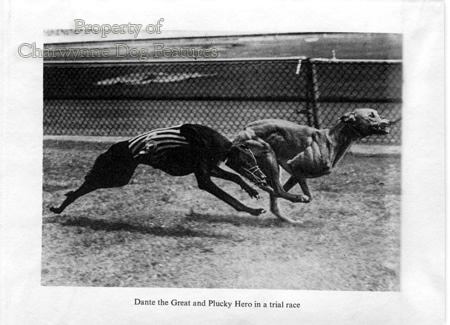

Early hunters bred dogs for their performance, that is how the sighthounds earned their keep; they were bred to be useful never to be primarily pretty. Increasingly in the modern world, appearance is all; image matters more than substance and physical looks can outweigh character and performance. This has sadly long been the case in the canine show ring. We all like a handsome dog but a dog that can nothing else but pose has a limited appeal to sportsmen. The highly successful racing Greyhound Mick the Miller and the impressively effective coursing Greyhound Master McGrath were always described as rather plain and unremarkable, until they started running, that is! Master McGrath was rather thick-set, with a shortish neck and for some, was too compact. Mick the Miller had no obvious outstanding features but also no significant defects. They have been referred to as the ugly ducklings of the leash and turf but only out of envy. Both had wonderful symmetry of build and superb balance; these are essential attributes in a running dog but are usually only revealed in performance.

No Exaggeration

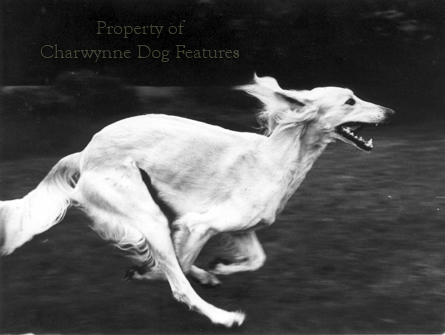

Neither of these outstanding hounds displayed any sign of physical exaggeration. At Crufts in 2010 one sighthound judge commented: “I am concerned that over-angulated hindquarters seem to be becoming more prevalent, too long from the point of stifle to the hock. Not only does this spoil the balanced and symmetrical outline but is a serious fault as far as the functional capability of the Whippet is concerned.” This is a point very well made. The seeking of unnatural movement in the ring is also a curse. In her book on the Saluki, Ann Chamberlain writes, on ‘gaiting’: “The Saluki is a hunting breed, used for thousands of years in every terrain imaginable. To attempt to define the ‘show gait’ or the ‘proportion’ of the dog (i.e. in the breed standard, DH) after all these years seems not only unnecessary but also superfluous.” I doubt if such a wise opinion will be heeded.

Angulation for Exhibition

In his most informative book The Dog – Structure and Movement of 1970, vet and sportsman, RH Smythe, writes: “In the running dogs such as the Greyhound, the change (to extra angulation, DH), whatever it produced in the matter of appearance, has certainly done nothing to improve performance. The racing Greyhound of today has a straight hindlimb and tibia of moderate length and it executes a large number of short, rapid strides, attaining a very high speed. The exhibition Greyhound with exaggerated angulation, ‘standing over a lot of ground’, and with a very much longer hind stride, both behind and beneath the body, actually carrying the hind feet past the shoulders in the forward section of the stride, cannot catch the smaller dog with the straighter stifle and hock, simply because the fewer, longer strides cannot compete with the many shorter ones.” In these few words, he makes many points on conformation, but the key point lies in the bare fact that if you wish to perpetuate a real sighthound breed, as the pioneers in that breed strove mightily to do, you have to ignore show ring fads and breed for function. A sounder animal emerges quite apart from the genuine hound.

Visualisation

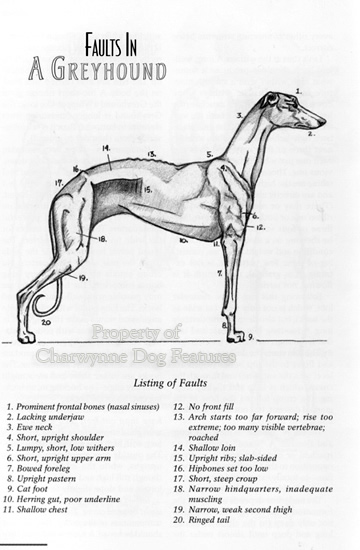

The design specification, as always with a hunting dog, a sighthound especially, is to find the ideal match between quarry, country and conditions on one hand and speed, determination and hunting instinct on the other. The best judge of a sighthound is a man who has hunted one himself, a man who visualises the dog before him in the ring in the chase. But he has to possess some basic knowledge of the fundaments of hunting dog anatomy or he has no right to be in the ring as a judge. I see judges at shows who never look at the feet, never test the condition of the loin, don't examine the bite, and reward entrants with slab-sides, an incorrect slope to the shoulders and rib-cages which lack lung-room. That can only reward bad breeding, leading to a production-line of mediocre dogs; winning dogs get bred from! Lurcher shows may be mainly a bit of fun, but KC-approved shows for the sighthound breeds identify future breeding stock.

Abnormal Gaiting

In her book on the Afghan Hound, Margaret Niblock writes: “The Standard succinctly describes the gait of the Afghan as ‘smooth and springy with a style of high order’ with a proud head carriage, far-away gaze and raised tail. This cannot be achieved if the animal is restrained by a tight grip on a short lead, or ‘strap-hanging’ as can be seen in terrier handling. It is miserably uncomfortable for the dog, which, choking and coughing, leans even more heavily against the collar in a frantic effort to put his feet on the ground for balance. The result is an unnatural, stilted, flailing or ‘knees up’ action in front and unbalanced over-thrusting from the hindlegs, often accompanied by knocking hock joints and leaning away from the handler. This misuse of hind muscles particularly in gangling youngsters, may cause permanent damage and unsoundness.” She was writing this over thirty years ago; if anything, abnormal ‘gaiting’ and stringing exhibits high up on choke chains is even more prevalent now than then. I have even witnessed it at lurcher shows.

Needless Size

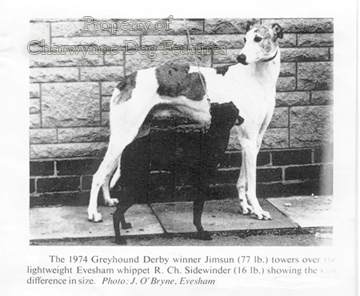

I don’t understand the justification for so many sighthounds, including lurchers, being so huge! It is worth remembering that the main reason why show Deerhounds tend to be enormous is not need but origin. Deer hunters found that dogs over 28" at the withers lacked performance and quickly passed them on to the early show breeders. No Waterloo Cup winner has ever been thirty inches high. I regularly see lurchers at shows which stand 30" and which must weigh 90-100 lbs. I would have thought that even on Salisbury Plain or around Newmarket, 60-70 lbs was easily big enough. I have written earlier that the superlative coursing Greyhound Master McGrath, three times winner of the Waterloo Cup, believed by many to have no equal for pace, cleverness and killing power, weighed 52-54 lbs. Wild Mint weighed 45 lbs and Coomassie only 42; both were superbly effective coursing dogs. They were judged and rated entirely on their performance, the sternest and most valid test of all. Any breed prized and valued purely for its size, from a hopelessly bulky Mastiff to a needlessly giant Great Dane is going to pay a penalty too in bone problems and not just late in life.

Shaped by Function

But whatever their size it is possible to judge these admirable dogs more effectively. If we are going to assess them, let's do it properly. If we betray all the remarkable work, not just by the pioneers in each pedigree breed but in long dogs the world over, we will gradually lose a precious feature of the timeless man-dog relationship, as well as an ancient hunting feature. A hound which hunts using its speed must have the anatomy to do so. Immense keenness for work will always come first but the physique to exploit that mental asset comes close second. Hunting ability rests not just on pace. A sighthound must have a long strong muzzle with powerful jaws and a level bite, with strength right to the nose-end of the muzzle. How else can it catch and retrieve its quarry? The nose should be good-sized with well-opened nostrils, for, despite some old-fashioned theories, sighthounds hunt using scent as well as sight. Their function shaped their design, a function demanding performance, both from the quarry and the owner.

Protective Coats

Smooth-coated sighthounds are sometimes handicapped by too little coat, lacking protection from wire and chill winds. Whilst not advocating a change of jacket in any sighthound breed, I can see operational merit in a stiff-haired, wire-haired or linty coat. Ibizan Hounds can carry such a coat, but it’s one not favoured in the show ring. The jacket of any sporting dog should shed the wet not hold the wet. Waterproofing comes from hair density and texture not profusion of coat; if you look at the originally-imported Afghan Hounds and Borzois and then compare their coats to today's specimens, you can see how function has forfeited to fashion. Salukis develop a different coat in our climes, but that does not mean a needless handicap in their primary function – as a cursorial hound. We need them to feature what is best for them, here, not us.

Fitness for Function

But the best physique is squandered without keenness in the chase and immense determination, an alert eager expression in the eye indicates this and is essential. Every sighthound judge has to ask himself: will this dog hunt? Can this dog hunt with this anatomy? Better function-judging, based on a more measured assessment, should lead to the production of better dogs. With coursing here confined to the past, we owe a great deal to the rich sporting heritage of our sighthounds and must breed canine sprinters to be just that. Country sportsmen have too much sense to allow the show ring sighthound breeds to degenerate into the pretty-polly state prevalent in far too many pedigree dog breed show rings. Lurcher shows, for example, are more a day out than any identification of future breeding stock: a bit of fun; the only real test for such a dog is in the chase. But that 'bit of fun' can raise standards too if the judges' criteria are sound. Who wants to win with an unsound incapable dog?

Condition for Competition

In her book Sighthounds Afield, AuthorHouse USA, 2004, Denise Como writes: “Whether lure coursing, oval track racing, sprint or straight racing, open field coursing, hunting, hiking for miles, or any combination of these activities, an unfit hound is going to get injured. These are strenuous sports. An out-of-condition hound is a prime candidate for pulled and torn muscles, ligaments, and tendons, cramping, heat exhaustion, dehydration, and other forms of extreme unpleasantness.” The condition of your sighthound should always be a matter of great personal pride and I am saddened when I hear of a show exhibit in one of these breeds being knowingly under-muscled to obtain a ‘sleeker’ dog for the ring. To own a sporting breed is a privilege that should never be taken lightly. Every sighthound judge must honour their impressive sporting heritage and reward only those exhibits displaying the physique of a fast running hound.

Breed Points

Much is made in the show fraternity of breed points, or those physical characteristics that define one breed from another. In all hunting dogs, form is decided by quarry, country and climate. Coursing dogs tended to be stronger-boned than racing ones, with their lighter bones. The Irish Wolfhound and Borzoi needed greater size to engage the wolf. The smaller Cretan Hound, specializing more on hare can be almost Basenji-like. The Afghan Hound needed bigger feet and a more protective jacket. The Whippet has a relatively deeper chest than other sighthounds. The Mediterranean breeds display less chest-depth than most other sighthound breeds. Owners too exercised a preference in deciding that the Pharaoh Hound was to feature one coat colour, the Whippet any colour, but with some colours associated rightly or wrongly with performance. The Deerhound and the Wolfhound breeds had fewer colours in the gene pool. Syrian Saluki breeders preferred the crop-eared dog. The Borzoi shows a distinct rise over the loin. The Sloughi can be sharper-muzzled. Where such features support field performance then justification is there. And colour preferences usually represent human choice. What is regrettable however is for breeders to sacrifice field performance for show gain. Handsomeness purely for its own sake in such loyal, long-serving and ever-willing breeds is a commentary on the owners and breeders concerned. It insults the memory of all those eminent pioneer breeders who strove to bequeath to us outstanding hounds.

Real Sighthounds

In his book on the Greyhound, published half a century ago, the great sighthound expert H Edwards Clarke wrote: “It soon became apparent to the early breeders of the Greyhound that their fastest dogs, generally speaking, were cast in a certain common mould. In the fullness if time they came to associate such physical features as tall straight forelegs, strong loins, powerful quarters, with the fullest endowment of speed and stamina. In their minds’ eyes they created a picture of the ideal Greyhound, of the conformation that in their experience had proved to be the most reliable and consistent vehicle of the breed’s great intrinsic qualities. This commonly accepted standard of physical perfection was drawn up long before dog shows had ever been thought of.” All sighthounds function as such from the design of their anatomy; if we seek to change that design to suit a contemporary whim, we threaten their claim to be real sighthounds.

“A number of people take up the breeding of animals thinking that it is only necessary to purchase a few show specimens in order to turn out innumerable winners. No doubt they very soon find out their mistake…Dog-breeding seems an easy enough matter to those persons who have been accustomed to breeding mongrels or hardy animals of pure breeds. It is not until the novice takes up the breeding of the highly-bred, inbred show dogs that he learns to his surprise how many unsuspected difficulties may arise, and what complications may ensue.”

The Kennel Handbook by CJ Davies, The Bodley Head, 1905.

“The early owners of racing dogs raced them and the fastest dogs were those of a definite type. The fastest were the sires and dams most sought as progenitors. There is an association of bodily features which is conducive of great speed, so the type of dog which we know as the greyhound began to become a breed. And finally by the recognition of the fact that there is a definite association of physical characteristics, leaders found that they could also improve greyhounds by inculcating beauty into the breed without sacrificing speed. Then they began to compare them in groups to see which most nearly approximated what they thought was the composite of beauty and usefulness. In this way cliques were built up around all breeds which were interested not in the usefulness of the breeds but in the appearance. They gradually made their idea of beauty the goal and forgot usefulness. In fact they did the most absurd things and are still doing them…”

How to Breed Dogs by American veterinarian and the most highly experienced dog breeder of his day, Leon F Whitney, published by Orange Judd, New York, 1947.

“At the beginning of 1945, I was permitted to refer to dogs in a broadcast talk for the first time since I began working for the BBC…One of my points was that the breeding of dogs was far too haphazard an affair and not sufficiently based on available knowledge. In addition, I pointed out some of the reprehensible things that were going on and cited the crossing of the Borzoi into our Collie in order to secure a long narrow head in place of one of the broadest and brainiest of doggy skulls, with disastrous results on the temperament and intelligence. I gave other instances equally foolish, but the aim of what I said was a plea that all this hit and miss experimental breeding could be put on a much surer and scientific basis if representatives of my profession, geneticists, and the Kennel Club, could meet and discuss the problem…but the doggy world and its all-powerful ruling body passed me by. I was even the subject of attack in the dog papers…”

The Right Way to Breed Dogs by RCG Hancock, BSc, MRCVS, Elliot Books, 1956.