330 Bobbery Packs

THE JOY OF THE BOBBERY PACKS

by David Hancock

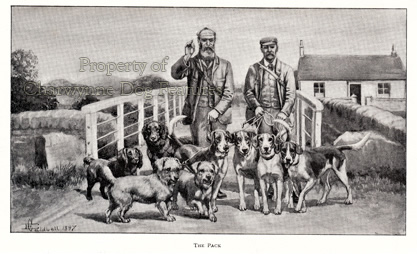

“The pack was mixed, consisting partly of foxhounds drafted from other kennels to save a yard of rope – these were the intended mainly for show; partly of a miscellaneous assortment of breeds, among which a basset-hound seemed to have taken the leading part. These last were relied on to do the work, particularly old Trueboy, an ancient hero of uncertain origin, whose unerring scent and mellow tone proved of incalculable value to his less gifted brethen.” Those picturesque words by HR Heatley come from a piece entitled ‘A Bobbery Pack’, contained in The Badminton Magazine of 1901, and sum up very succinctly the essential elements of such a group of sporting dogs.

“The pack was mixed, consisting partly of foxhounds drafted from other kennels to save a yard of rope – these were the intended mainly for show; partly of a miscellaneous assortment of breeds, among which a basset-hound seemed to have taken the leading part. These last were relied on to do the work, particularly old Trueboy, an ancient hero of uncertain origin, whose unerring scent and mellow tone proved of incalculable value to his less gifted brethen.” Those picturesque words by HR Heatley come from a piece entitled ‘A Bobbery Pack’, contained in The Badminton Magazine of 1901, and sum up very succinctly the essential elements of such a group of sporting dogs.

In the wake of the anti-hunting campaign, it is fair to conclude that once the class-warriors have ended the sporting life of men in pink coats, they may concede a need for vermin-control nonetheless. This could lead to the licensing of small operators, using dogs and guns, to reduce fox and rabbit numbers in specified areas. However unsatisfactory in the whole, it could see an increase in the number of 'bobbery packs', usually collections of small hounds and terriers, to drive vermin to the waiting guns.

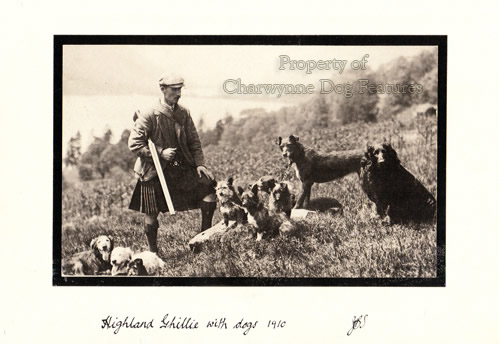

Ever since reading Roger Free's 'Beagle and Terrier' as a fourteen year old, hunting with a small pack of assorted dogs, has appealed to me. He wrote in times when individual freedom had greater respect but a future need for vermin-control could see his style of operating in the field on the way back and to a greater degree. The remarkable Sir Jocelyn Lucas used to hunt with his renowned Ilmer pack of Sealyhams. Lucas wrote that he didn't want a dog that becomes tired after walking a mile and lamented the "most appalling-looking terriers described as 'working type'." There is no need for a bobbery pack to feature unsound dogs or ugly brutes.

Roger Free kept and hunted a small mixed pack of 14" Beagles and Terriers for hunting rabbits for the gun. 'Dalesman' described Free's pack as one "which any huntsman might be proud, because they have all those attributes which go towards excellence. Some of these are bred in the hounds -- courage, stamina, nose and tongue -- but the rest must be taught and instilled with patience and knowledge of hounds and their work." But what a challenging self-set task for any ambitious sportsman. Free, not surprisingly, considered that more pleasure was to be derived from hunting your own hounds than from being a follower of a pack hunted by another.

Free argued that whereas gundogs are taught by man, scenthounds frequently learn to hunt without the assistance of man and are therefore more self-reliant. He wasn't decrying the merits of gundogs but stressing the need for a different approach to the training of hounds. He advocated choosing a dog which was not afraid to look you in the eye. He preferred to guide a dog rather than 'break' it. He looked for boldness, perseverance, eagerness and biddability. He emphasised the latter and was aware of the menace of self-hunting hounds, oblivious to all recall. He trained his terriers the same way as his hounds and used Lakeland or Fell Terriers, but was always worried about their colour concealing their whereabouts from the guns.

He concentrated on hunting the hounds and did not himself carry a gun. He normally used four or five couples of Beagles with two or three terriers, finding the latter better in really difficult cover. This meant handling a dozen dogs singlehanded, a testing task. Some sportsmen find controlling one gundog quite beyond them! Generally speaking, terriers and scenthounds demand far more skill in their training than gundogs, partly because of their different instincts and partly because they are often expected to operate in the field as a pack. Gundogs have been bred for centuries to respond to human direction in the field; terriers and scenthounds have striven for several centuries to defy all human instructions!

In his informative "Secrets of Dog Training" Brian Plummer writes, with deliberate understatement, "Terriers despite their small size, are sometimes far from easy to control. In addition to the fact that most terriers still retain a strong inclination to hunt any type of animal or bird whose scent crosses their paths, the majority are particularly eager to take offence from another dog." It is interesting to note that most experienced and well-regarded terriermen dislike dogs that are too hard; many outspoken but less experienced working terrier fanciers will often boast of the sheer aggression in their dogs. This to me is a sure sign of tongue preceding brain.

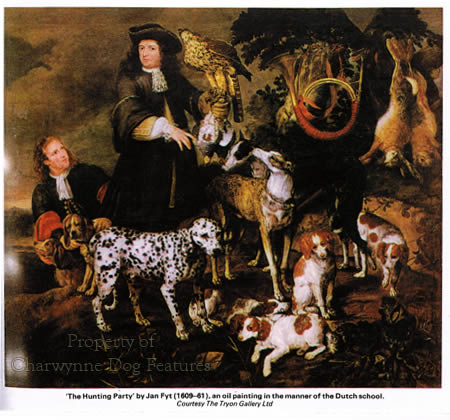

Small-time hunting, with a small pack of hunting dogs, does of course take place all over the world. In less crowded countries all sorts of quarry are hunted. In the United States, coon-hunting is conducted from the beaches of Florida to the drains of Michigan. Sometimes pure-bred hounds like the Black and Tan, the Redbone, the Treeing Walker, the Plott and the Bluetick are used. Less well known breeds like the Catahoula Leopard Dog and the Black Mouth Cur are also utilised. American coonhound breeders have found that the open-trailing tendency is dominant over still-trailing, a lack of quality voice is dominant over the beautiful classic hound 'music' and the tendency towards poor scenting ability is dominant over keenness of scent. Breeding plans therefore need great care.

These hunters have tried bird-dogs for their hunts but not surprisingly found that they hunted with their heads up and an inclination to quarter rather than trail. Springer spaniels have been proved to be good trailers and to cross successfully with hounds. Contrary to expectations, these crosses did not produce good coonhounds: Irish Setter X Bloodhound, Pointer X Bloodhound, English Setter X Foxhound and Pointer X Foxhound. Crosses between farm collies and hounds produced sound coon-hunting dogs, displaying pace, eagerness, stamina and voice, which although lacking the mellowness of pure hound music carried well over long distances. This is valued in this form of hunting.

A breed no longer used here in Britain for sporting purposes but found useful overseas is the Airedale. Perhaps it was a mistake to call this breed a terrier; in France it would have been called a griffon, and expected to hunt the bigger game. The Airedale is appreciated much more in the United States as a working dog than here, the country which produced it. Fifteen years ago the first annual Hunting/Working Workshop of the Airedale Club of America was held. This workshop planned events to prove that the Airedale could still be a versatile hunting dog. In three days, on the Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area near Marion, Ohio, the Airedales were tested in: upland bird hunting, trailing and tracking fur and then retrieving.

Then the North American Working Airedale Terrier Association was formed with these goals: to improve the physical soundness and temperament of the breed, to participate in Schutzhund or protection dog training, to promote tracking events and other working tests. I know of no such tests in Britain. For anyone forming a bobbery pack for mink, the Airedale would be a good choice. I wonder though just how dormant the hunting instinct is after a century of neglect. The breed was developed to combat the prevalence of pine-martens (now being reintroduced), polecats and otter in the Aire Valley around 1850.

Breed historians still claim a part-ancestry with the Otterhound, the type stabilised in the packs. I am not convinced. There was a northern hound breed, identified in the middle of the 19th century as the Lancashire Otterhound, black and tan and wire-coated. This hound had a distinguished record against water-based vermin and possessed a distinct breed type. The early Airedales had larger ears and a denser, closer waterproof coat. It would be a source of great pleasure to all those who mourn the loss of our Airedale as a sporting terrier to see this admirable native breed employed in the hunting field once again.

In his 'The Dog in Sport' of 1938, J Wentworth Day wrote: "Nobody shoots rabbits on sunny Sussex downlands with such packs of slow and musical beagles in these hurried days. We hurry so much we miss the half of life, the charm of quiet things, the simplicity of the easily attainable." Roger Free knew of the charm of quiet things and found them easily attainable. If packs of hounds ever have to be dispersed, a hunting future in bobbery packs would be one way of employing the best bred dogs in Britain -- and perpetuating their ingrained skills. Perhaps those filling their wallets but missing the half of life in the City should now be seeking a country property and a dozen sporting dogs to restore their sanity. In so doing they would be going down a well-worn and rewarding trail. There is sheer sporting joy in hunting with bobbery packs!